Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive? I don’t think many will feel the same way that William Wordsworth did about the French revolution when they look back on June 2016 and our referendum on Europe. For this was no springtime of peoples, no logical debate in Plato’s republic, and no political Glastonbury either. And it has not produced the national catharsis that some hoped for. No one is snatching a few hours’ sleep this evening thinking, wow, that was just what we all needed, give us more of it.

This referendum was about Britain and Europe. But it was also a disturbing revelation of the way we now do politics. As such it cannot help but be a reflection on David Cameron. This was his show, prepared over years, not weeks. He produced, designed, directed and starred in it. It reflected his way of governing, his model of leadership, his priorities, his politics and his attitude to Europe. And it has been a shabby muddle for which he must take responsibility.

Those of us who have not lived through all-out war should be hesitant before drawing the parallel that follows. But this has been the first occasion in my life when I have experienced a peacetime moment more normally associated with war, in which you realise that everything you know may soon and suddenly disappear, the good along with the rotten. In my view the responsibility for that lurching doubt about the future lies not just with Cameron but sits squarely at the door of the referendum process itself.

Perhaps some on the leave side of the argument, like the poet Rupert Brooke when war broke out in 1914, have thanked God for matching us with the referendum’s hour. Perhaps too it is useful, from time to time, to be reminded of how close we still live to a state of nature, amid all our consumerist and technological hubris. Nations are not eternal. But the two simple words that have come increasingly to mind over the past month are those that were used so often by the generations who emerged intact from war in 1918 and in 1945. Never again.

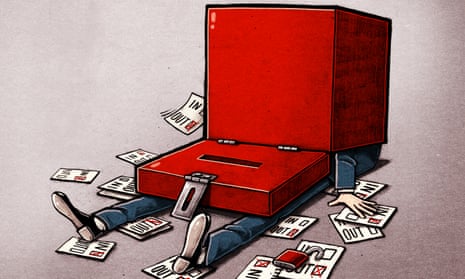

Referendums have insinuated themselves into our politics in the last half-century. Like the banker’s bonus, the xenophobic tabloid, the cold call, the urban fox and a lot of the other unwelcome aspects of modern Britain, no one ever positively invited them into our lives. But they have gained a foothold among us now and, like the bonuses, the xenophobes, the calls and the foxes, it’s time we drew the line much more tightly around them. It is not too late.

Cameron has simply been too weak to do this and, being weak, has made the problem worse for his successors. His whole approach to the referendum has been ad hoc, because he has shown himself to be, in the final analysis, an essentially ad hoc politician. His dominant view of the world does not go far beyond the view that Britain is, on the whole, better governed by the Conservatives. Europe, and everything else, is seen through that prism.

Cameron has never, even now, resolved his own position on Europe. For 24.9 of the past 25 years he has thought three incompatible things about the EU: that he dislikes it, that we should be part of it, and that there must be a referendum about it. A better leader would have sorted these competing instincts into order, would have chosen between his dislike of Europe and his desire to be part of it and made the referendum subordinate to that decision.

Instead Cameron almost drifted into the referendum. He appeared to think until the campaign actually started that it would be a repetition of the first EU vote in 1975, in which majority opinion would endorse the overwhelming consensus of the ruling class in favour of remaining on the terms he had negotiated. It didn’t work out that way for many reasons: among these, I suspect, was a feeling among post-crash voters that economic warnings do not really apply to them but only to the distant rich and corporate. Either way, the referendum became more of an angry act of payback than a measured act of democratic participation.

This was far from being an isolated referendum. The referendum is now the weapon of choice for populist parties of left and right. The European Council on Foreign Relations pointed out today that populist parties around Europe now propose a total of 32 referendums on issues ranging from EU membership to refugee quotas. A vote for Brexit, says the council, could be the advance signal of a “political tsunami”. Since the survey makes no mention of the Catalonia independence referendum that may emerge from a victory for the left in Spain’s election on Sunday, the figure of 32 is probably an underestimate.

The fact that populists like referendums is not necessarily an argument against them. But it is certainly a reason to reflect much more carefully about the place of referendums in our systems of representative government. Every referendum concedes the argument that parliament is not always sovereign. For a political system such as Britain’s, which is centred on a feudal concept of sovereignty, that is a slippery slope.

Over the past half-century, Britain has drifted into a system of referendums that has few common rules or strict criteria. We talk about referendums being reserved for major constitutional issues, but without defining what such issues are. Sometimes a referendum is binding, sometimes not. We say referendums are special, but we have few special rules to govern them. We are inconsistent about their use. In the UK devolution sometimes involves a referendum and sometimes not. European treaties can be subject to referendums but other treaties are not. The alternative vote was put to a referendum but proportional representation in European elections was not. We do not specify that a referendum cannot override fundamental rights.

There may, in certain circumstances, be an argument for referendums in our politics. But the argument has to be better than that we have had some referendums in the past or that a lot of the public would like one. People will always agree they want a say. Yet it is far from obvious that a system of referendums strengthens trust in democracy. Neither Ireland nor Switzerland, where referendums are more common, seem to vindicate that. Germany’s constitution is strongly rooted in the opposite view. And if an issue is major enough to require a referendum, why is it not major enough to require a high level of turnout or an enhanced majority of those voting, as should be the norm?

Cameron has just put Britain through a stress test of the proposition that a major issue can be best resolved by a referendum. Politically, perhaps he had no choice. But the result actually means Britain’s place in Europe is messier, not clarified. The referendum has conferred less legitimacy on politics, not more. It has pushed the nations and communities of Britain apart, not brought them together. It has allowed a bad press to behave even more irresponsibly.

After what we have experienced in the past month, we need political reform more than ever. But the verdict on referendums should be a ruthless one. Never again.