China's search for a new path is fraught but necessary

Andrew Leung says the debate over the path to transformation is fierce but may be reconciled

There are many signs that China has now reached a historic watershed. First, the economy is changing towards slower, but more balanced, equitable and sustainable growth, to be driven by consumption instead of capital investment and exports.

Second, according to researchers at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, an increasing number of currencies are moving in sync with the renminbi, treating it as a "reference currency" instead of the US dollar.

Third, for the first time, China tops the world in patent applications. Fourth, a rising citizenry is succeeding in reversing government decisions on such matters as social justice, the local environment and press freedom. Fifth, "labour re-education" is to be scrapped. Sixth, China's new leadership is now fighting corruption as a top threat to the nation's stability.

Meanwhile, externally, China has grown too big and too globalised to continue with Deng Xiaoping's famous dictum to "lie low and bide its time". A nascent blue-water navy is taking shape and the nation has become more assertive over its maritime territorial claims.

According to a report by the European Council on Foreign Relations, China needs to enter into a new era. As the report put it: After Mao Zedong's political revolution ("China 1.0") and Deng's economic revolution ("China 2.0"), what comes next must be a "China 3.0".

The report, a collection of essays by some of China's most influential thinkers, indentifies three traps or crises in which China finds itself. How to respond to them is now the subject of intense debate.

"In the economic realm," the report says, "the main divide is between a social Darwinist New Right that wants to unlock entrepreneurial energy by privatising all the state-owned companies and an egalitarian New Left that believes the next wave of growth will be stimulated by clever state planning.

"In the political realm, the main divide is between political liberals who want to place limits on the power of the state … and neo-authoritarians who fear these measures will lead to a bureaucratised collective government that is unable to take tough decisions or challenge the vested interests of the … crony capitalist class.

"In the foreign-policy realm, the main divide is between defensive internationalists who want to play a role in the existing institutions of global governance … and nationalists who want China to assert itself on the global stage," it says.

The intensity of the argument, however, masks the nuances of these positions: they are not as diametrically opposed as they might first appear. For example, the so-called New Right does not advocate that China imports the kind of Western market fundamentalism that led to the financial crisis.

In any event, such debate does not fracture the collective leadership, as opposing ideas are, as a rule, discussed and reconciled through various expert groups, a feature of China's relatively efficient decision-making process. There is no administrative gridlock of the sort found in America's partisan politics.

Indeed, some ideas in the various intellectual camps deserve adoption. These include Ma Jun's "accountability without elections", and monitoring governance through civil society; Zhang Weiying's safeguard of individual "rights"; Pan Wei and Shang Ying's "Wuxi experience" of neighbourhood communities; and Wang Yizhou's diplomacy of "creative involvement" by providing public goods in the global commons commensurate with China's emerging status as a world power.

Sun Liping, who supervised Xi Jinping's doctoral thesis at Tsinghua University, identifies China's "correction predicament" or "transition trap" where accumulated problems have grown too difficult to resolve and reform is opposed by powerful vested interests. He says a social consensus must be built to tackle this predicament head-on as there is only "a fleeting historical opportunity to face this challenge".

China also has to grapple with a "middle income trap", in which countries of a certain per capita income tend to stall in productivity.

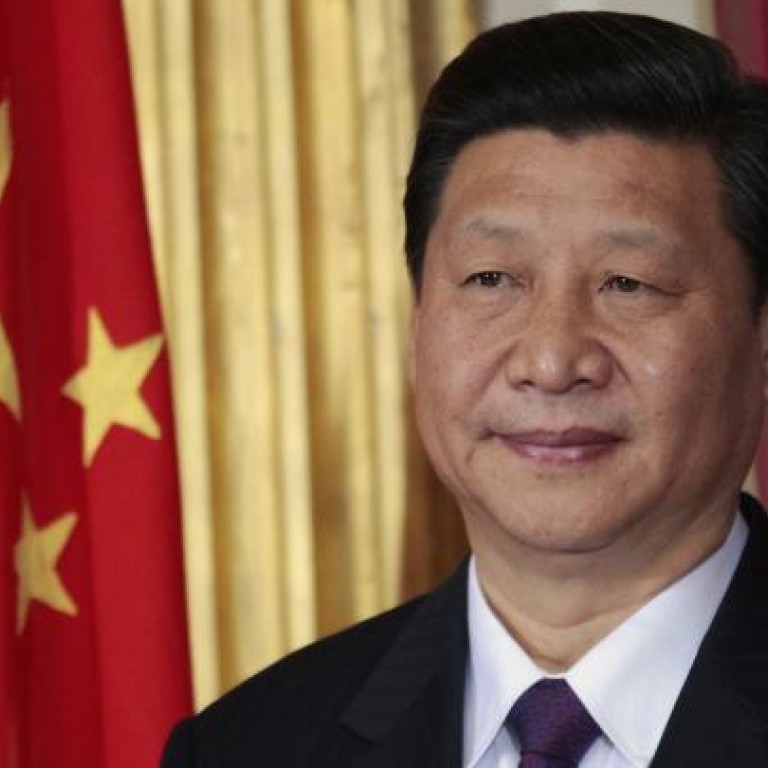

Party leader Xi talks of China's dream of a coming renaissance. However, with some seven million university graduates added every year, a rapidly growing, middle-class "Chinanet" generation is increasingly demanding greater legitimacy, accountability, openness and personal liberty. Absent meaningful democratic reform, any vision of a Chinese renaissance would not only remain elusive, but the very survival of the party risks being threatened.

There is a rumour that Alexis de Tocqueville's tome on the French Revolution has been doing the rounds among the top leadership. This may not be without foundation, for amid the crises and traps China is facing, perhaps democratic reform is the most critical of all.