Outside the historic chancellery building in Vienna’s Ballhausplatz 2 in early March, horses and carts ferried tourists languidly about the historic imperial centre while people sat outside the famous coffee houses enjoying the first rays of spring sunshine. They had no idea that Austria’s 33-year old chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, was about to lock the city down and force them into house arrest for the next few weeks.

The young chancellor had been studying the spread of coronavirus in neighbouring Italy with growing nervousness. After consultations with counterparts in far-flung places—Israel, Japan, Singapore and South Korea—on 11th March he became one of the first European leaders to introduce unilateral border closures. Although it was obvious that this precipitate action would have consequences far beyond his borders, Kurz’s instinct was not to call an international summit or co-ordinate with the rest of Europe, still less the United States.

This nationally-focused, fast-moving, action-hero-style leadership is the antithesis of established ideas about European unity and governance through consensus. It is also, however, emblematic of the way a rising generation of politicians are ruling across a continent in the grip of the Covid-19 crisis.

A couple of days after Kurz’s March press conference, Denmark’s youngest-ever prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, announced her own border closures not in an address in parliament, but in a Facebook post. In Germany, the youngest minister in Angela Merkel’s cabinet, 40-year-old health minister Jens Spahn, became the chief crisis manager. One of his first acts was to introduce an export ban on medical protective equipment, restricting its availability to other EU countries against the rules of the single market. The same happened in France where President Macron decided to confiscate all stocks of protective masks—including a consignment imported by a Swedish company destined for delivery to Italy and Spain.

In those two southern European powers so heavily hit by the virus, the politicians responsible for fighting the virus are also disruptors: former law professor and political outsider Giuseppe Conte and underdog-turned-prime minister Pedro Sánchez. Although they looked for European solidarity in this hour of need, they share the impatient instincts of their unruly peers.

Every crisis gives rise to a new cast of leaders with their own style, formative experiences and blind spots. This group marks a real generational shift, and could not be more different from the Third Way brigade of baby boomer Atlanticist neoliberals who led Europe through the financial—and euro—crisis a decade ago. The leaders of that last crisis were born in the 1950s and came to power through the traditional route of loyalty to established parties. They tended to regard globalisation as irreversible, and to see the EU as one part of the solution to managing it, and American leadership as another. As the world shook, they reflexively reached out to the US in the hope of building a new international architecture.

The new leaders do not pretend to be master builders. Instead, they are disruptors with a “move fast and break things” ethos inspired, in part, by Silicon Valley. For better or worse, these are not politicians with any inclination to try to take their continent back to the old status quo. They are more likely to look to Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs or Beppe Grillo (the comedian who turned Italian politics on its head by founding the Five Star Movement) for lessons than they are to look towards Helmut Kohl or FDR. This will have consequences not just for how they deal with coronavirus, but how they attempt to reorder the world once the crisis has passed. Despite their disdain for European protocols could it just be that, in the end, the continent will have reason to be grateful to them?

Egos with momentum

To understand the restless new governing style in Europe—and the suspicion these leaders have of working through traditional institutions—start by looking at how this new cohort won power in the first place. They are all risk-takers, united by a mission to break the political mould through a strategy of insurgency. All of them have sought to redraw the electoral map in their countries, either by creating a new party or reinventing a pre-existing one. While Macron and Conte came to power via the formation of entirely new movements, Kurz, Frederiksen and Sánchez shook up the old parties they had risen through, and built a new electoral base by forging novel coalitions across traditional camps—while cultivating personal popularity. All defied the odds and achieved something that seemed impossible. They developed a politics centred on mobilising new movements as opposed to relying on traditional parties to capture opinion. By forging online connections, they fostered intimate links with voters who had felt abandoned by the old mainstream.

Macron named his movement La République En Marche—often shortened to En Marche, which shares his initials—and spent months researching which issues were being neglected by the established centre-left and centre-right. The idea of being en marche, literally marching, captures a shared idea of momentum as the essence of leadership. Macron managed to cut the old established parties out of the conversation, and turn the election into a contest between himself and the National Front, a reframing of the French electoral system then formalised when the Socialists and Les Republicans were knocked out in the first round.

Kurz, nicknamed the “Macron of the East,” renamed the party list of the Austrian People’s Party as Liste Sebastian Kurz: Die neue Volkspartei (List Sebastian Kurz—the New People’s Party). He offered to break the cartel politics that had seen grand coalitions of the centre-left and centre-right govern his country for over a decade. By taking a hard line on immigration, he was able to forge a new coalition with the far-right Freedom Party, but then weakened that force to the point of virtual destruction by stealing its rallying cry.

“They are more likely to look to Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs for political lessons than Helmut Kohl or FDR”

Spahn—who presumably longs to be known as the “Kurz of the west”—has been trying to persuade Merkel’s CDU to follow the same path as the Austrian chancellor on immigration and integration. As the first openly gay politician to serve in the German cabinet, he has used his membership of a minority to take a tougher stance on diversity issues, unashamedly declaring himself “burka-phobic.”

Frederiksen, the energetic leader of the Danish Social Democrats, adopted a similar recipe for renewal on the centre-left: stealing a march on the migration issue from the far-right Danish People’s Party. She made a tactical decision to sacrifice support among cosmopolitan city-dwellers in order to reclaim working-class voters from the towns and the countryside—a more coherent version of the “blue Labour” strategy that some in the UK believe might have saved Bassetlaw and Blyth Valley for the party last year. And in Denmark, at least, it worked: decimating the electoral base of the far-right party and taking the social democrats back into government.

Pedro Sánchez, who is also known as “Pedro the handsome” had a more convoluted path to power. He managed to regain leadership of Spain’s socialist party in May 2017 and became PM 13 months later, less than two years after he had previously been toppled from the helm of the opposition. His big play was to displace the populist party, Podemos, on his left flank.

But most iconic of all is Italy’s Five Star Movement, a totally novel, anarchic upstart form of politics born on the internet. Although he did not set up the party himself, Conte was a complete political outsider who used it to become prime minister—and is now Italy’s most popular politician.

Rebel rebel

Today’s leaders are the children of globalisation—most have spent time living and studying in other countries—but they are rebellious children. They prefer flexible and rapid action to the slow grind of multilateral negotiations. Where Gordon Brown and Barack Obama organised a G20 meeting to chart a way out of the Lehman crisis, the first instinct of the Corona Generation was to seal their borders and renationalise supply chains. The politically-seismic migration crisis of 2015 was central to the rise of the new cohort, and—watching the EU and global governance spectacularly fail in the face of the emergency—it sharpened their focus on the national over the supra-national, and on action over diplomatic conversation.

They see the purpose of leadership as being to surf the wave of history rather than being able to -control it, and certainly not presuming you can rely on cross-border alliances and institutions to divert global tides. Even when they speak a language of idealism, they temper it with pragmatism. Spahn’s favourite quote—which has a prominent place on his Facebook page—could be the motto for the whole generation: “What you can’t stop, you should welcome right away.”

The same applies to the currents of domestic politics. Instead of letting populists make hay out of anti-migration feelings, these rulers tend to channel the same resentment in service of their own interests. Kurz and Frederiksen saw early on that they could outflank the populist parties and make them irrelevant. Meanwhile Macron and Sánchez posed as the only alternative to populism, in the process provincialising other broadly centrist forces such as the established socialists and republicans in France and also the newer, centre-right Ciudadanos in Spain. Although Macron and Sánchez started out being welcoming towards migrants, they have seamlessly corrected their course in line with changing public opinion.

“Spahn’s favourite quote could be a motto for the whole generation: ‘What you can’t stop, you should welcome at once’”

The continent’s new leaders demonstrate the same pragmatism when it comes to the role of the state. Even those on the right are much less neoliberal and more interventionist than the Lehman generation. In the global financial crisis, there was rhetoric about the Great Depression and FDR’s New Deal, but even those social democrats who demanded a stimulus in 2008 were cautious about its scale; still feeling constrained by the lessons of Thatcherism, they erred on the side of conservatism in fiscal and industrial policies. The new generation are much more interventionist—and not just in economic terms. While Bill Clinton declared “the era of big government is over,” the new leaders embrace a muscular role for the state even if they have a pretty flexible understanding of exactly what this involves.

When the economic consequences of the coronavirus crisis became obvious this generation of leaders moved quickly in favour of massive state interventions. Macron is a former investment banker who was attacked from the left as a closet neoliberal when he led a controversial charge to reduce the French deficit. But when the storm hit, he quickly adopted the most expansive employment scheme in the world: the state that he runs is currently paying the salaries of almost three quarters of French employees. Macron also decided to regulate the price of disinfectants and confiscate stocks and the production of medical protection equipment.

In Italy, in spite of the libertarian roots of his party, Conte has dived deep into the minutiae of economic management. His government even fixed the price for masks at €0.50. But it is this cohort’s willingness to countenance lockdowns, to close borders and introduce surveillance systems that perhaps best reveals their postmodern and muscular pragmatism.

These leaders’ attitudes to international relations are also strikingly different from the Lehman generation’s. They definitely do not share its instinctive Atlanticism. The US is hardly mentioned in interviews, statements, or profiles of these politicians. Perhaps this is the product of the fallout of the Iraq War, which most of them experienced as very young adults. They emerged into a world in which America no longer played the purportedly “positive” interventionist role of the past.

This generation of leaders is not afraid to speak up against Trump. Macron trolled the Twitter President by responding to his decision to withdraw from the Paris climate deal with a promise to “make our planet great again.” Frederiksen boosted her domestic popularity and her global fame by responding aggressively to posturing Trumpian talk about buying Greenland.

The American global order is over for this generation, as can be seen from their interest in looking for new partners. During his first state visit to the US in February 2019, Kurz noted that he already had four meetings with Russian president Vladimir Putin in 2018. Italy’s young foreign minister Luigi di Maio is also called the “Chinese” minster as he works on -building a closer relationship between Rome and Beijing. Conte himself wants to revisit the sanctions the EU imposed against Russia in connection with Ukraine, and Macron too inclines towards a European rapprochement with Moscow.

Both European and not

The most paradoxical aspect of these new disruptors is their attitude to Europe. They are both more quintessentially European than any past generation of leaders, and yet at the same time, more dismissive of the current EU. They are part of the Erasmus/easyJet generation and yet their political awakening was defined not by the institution-building of Kohl and Mitterrand, but rather by the rise of Euroscepticism and the fragmentation of the euro, the refugee crisis and—not to be forgotten—Brexit. They all saw Britain’s departure as a sign of how the EU could crumble if the institutions in Brussels failed to adapt to the impatience of voters. They have been divided over the EU’s €750bn “recovery fund,” with Macron, Sanchez and Conte leading the charge for grants while Kurz and Frederiksen have made common cause with the Dutch and the Swedes to insist that support should come in the form of repayable loans.

And yet, even their criticisms of the EU flow from a genuine desire to rekindle continental co-operation, and to reform and renew the body that is still tasked with that. As Kurz put it in an interview at the beginning of his chancellorship: “Macron has the will to change Europe for the better, which, as a citizen of Europe and an Austrian politician, I am very glad about. I will do everything I can to support him and indeed others who are resolved to change and strengthen the EU.” Sánchez goes further: “I declare myself a militant pro-European.” Even Conte, often seen as the head of a Eurosceptic government, declared: “Some people say we wanted to challenge the EU, I say we actually want to give it a shake to revive it.”

Hope without faith

Just as he was first with border controls, as the crisis eased Kurz was the first EU leader to announce a lockdown exit strategy, again closely followed by Frederiksen. Coffee houses in Vienna are re-opening and there is a promise to return to some kind of normality. But what kind of new normal will the corona leaders build? Will they be interested in fundamentally changing our daily habits and ideas about the world? And what will that mean for the future of Europe?

The short-term consequences of Covid-19 have shaken the European project more fundamentally than the refugee or euro crises—the renationalisation of policy, the closing of borders, disruptions to the single market and supply chains. The very idea of self-isolation is a defeat for the European ideal: interdependence itself is on trial, seen as frailty or a threat, rather than an aspiration.

Faultlines are emerging between those focused on saving lives, and those prioritising saving jobs; between decision-makers who want to localise production of strategic assets, and defenders of free cross-border commerce. The first reactions in March seemed dire for European integration: leaders sought shelter in exclusively national solutions, while continental co-ordination and even co-operation was absent.

But looking ahead, there is reason to hope. The roots of today’s Euroscepticism lie in the visionary leadership of earlier generations who ripped down borders, scrapped national currencies and bound Europeans not just into a single market for goods but also, and more controversially, for labour too. They hoped that building interdependence would bind the continent into a community of fate, and that economic integration would be followed by political unity.

For that generation, interdependence would act as a balm to heal historical grievances between the nations. Their vision may have helped the continent escape from its bloody history, but the interdependence slowly became a grievance factory, as opposed to a grievance cure. The euro created tensions between debtors and creditors. Free movement put downward pressure on wages and welfare states in the host countries, and created brain-drains and hollowed-out communities in the countries that the migrants had left behind. The absence of borders in the Schengen area fuelled nativist fears about refugees crossing the continent. While a majority of people glory in the opportunities of an open Europe, substantial minorities feel it has deprived them of control and left them vulnerable.

In the same way that Richard Nixon was better placed than a peace-loving internationalist to reach out to Communist China, this generation of leaders could turn out to be the ones to re-energise a wilting European project. Precisely because of their hard-nosed and pragmatic way of doing politics and lack of any European religion, they have the credibility to make a new case for co-operation. Their mission will never be about tearing down the barriers between states, markets and peoples. Rather, it is to prove to Europe’s citizens that interdependence can be made safe again.

The true believers who sought European integration ultimately only bequeathed a populist backlash. If this new generation of leaders, who start out unencumbered by any special faith or loyalty to the EU, nonetheless come to believe it is the best way to further the interests of themselves and their country, then they might be able to persuade their voters of the same. And if so, just maybe, the new disruptors can leave the European Union stronger than they found it.

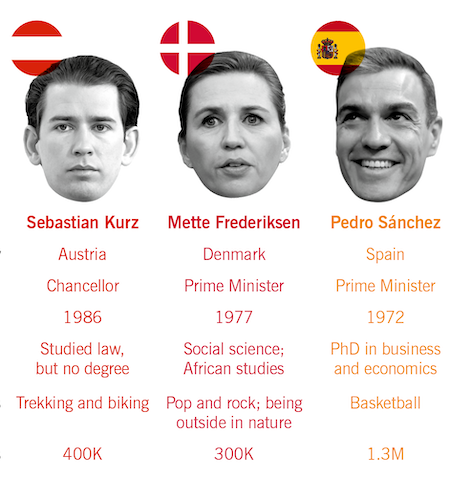

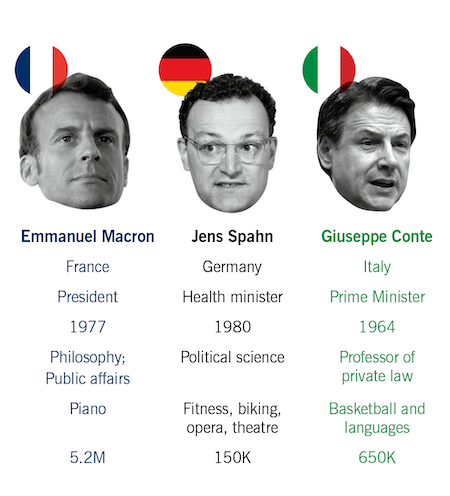

Europe’s disruptors: The impatient faces of a continent’s new generation of leaders—country, position, year of birth, education, hobbies, Twitter followers