Leading from the Centre: Germany`s New Role in Europe

27 Jul 2016

By Josef Janning and Almut Mölle for European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)call_made on 13 July 2016.

Over the last decade, Germany has taken on its natural leadership role in the EU’s economic and monetary affairs. This brings the “German question” – how the rest of Europe should deal with Germany’s power – back to the centre of the European project. More recently, Berlin has also taken a greater role in foreign and security policy. The push by President Joachim Gauck, Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, and Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen for a stronger Germany in foreign and security policy in recent years has been overtaken by the need to respond to crises and wars in and around Europe.

Berlin has played a pivotal role in responding to Europe’s three major foreign policy challenges of 2015 – the conflict in Ukraine, the latest eruption of the euro crisis in Greece, and the refugee crisis – arguing for a joint European response. Each of these crises has been shaped by the choices and actions – or lack thereof – of German leaders. This growing agency is reflected in the results of the European Council on Foreign Relations’ annual Scorecard, which ranks countries according to their influence on Europe’s foreign policy, and placed Germany top in both 2015 and 2016.

Berlin’s leadership model has, at times, appeared unilateral,reflecting Friedrich Schiller’s line that “the strong is strongest when alone”. Chancellor Angela Merkel and her government did engage with other member states on these crises – for instance, with France and Poland on Ukraine; with France, the Netherlands, other northern Eurozone countries, and the European Commission on the Greek question; Italy, the European Commission, and countries along the Balkan route over the refugee crisis; and with the Dutch EU presidency and the Commission on the Turkey refugee deal. But, in each of these cases, it was Berlin that took responsibility for the timing and the design of initiatives.

It was during the latest of these crises – caused by unprecedented numbers of refugees arriving to the EU in the space of a few months – that Germany’s leadership began to falter. Germany’s “refugees welcome” policy prevented a backlog of refugees gathering in south-eastern member states, but could have caused the collapse of the EU’s migration system as set out by the Dublin II Regulation, which states that refugees must seek asylum from the first EU country they arrive in. Berlin issued several calls for solidarity and for the burden of supporting refugees to be shared across Europe –but with little effect.

Instead, the government shifted its attention towards negotiating a solution with Turkey, the gateway for many of those arriving to Europe from the Middle East. Germany negotiated a “one in, one out” deal with Ankara in March 2016 – under which Europe agreed to resettle Syrians from Turkish camps in exchange for Turkey accepting Syrians returned from Greece. The agreement was officially made on behalf of the EU, but in reality this was very much a deal pursued by Merkel herself. Facing growing domestic pressure and elections in three German federal states, she needed to bring down the numbers of refugee arrivals to prevent popular unrest. For the first time after a decade in office, Merkel’s performance at the EU level and in international crisis management was directly tied to her standing in domestic politics. As a result, Berlin led the EU into a fragile and controversial agreement with Turkey.

This paper analyses Germany’s leadership performance and considers how lasting its new role will be – in particular, in European foreign policy. First, the paper discusses the concept of German leadership, before mapping how the EU, Europe’s neighbourhood, and the world at large look through the eyes of Berlin policymakers in 2016. The paper discusses recent cases in which Berlin has been instrumental in shaping a European foreign policy response, and considers how far German leadership in these cases has been in sync with the overall European interest.

Finally, the paper makes recommendations for how German leadership can contribute to the strength and health of the EU as a whole.

A shift in German leadership?

Germany’s ambiguous role in Europe

The question of Germany’s role in the EU has become a topic of debate and controversy over the past few years. Two crucial questions have repeatedly been raised. First, whether Germany’s interests can be reconciled with those of the EU as a whole; and second, whether Germany is willing and capable of being more than a geo-economic power that relies on economic rather than political tools to pursue its interests. The dominant narrative about Germany’s role in Europe acknowledges Berlin’s strength and willingness to invest in European solutions (if only on its own terms). This places high expectations on Berlin’s leadership in both the internal and the external dimensions of EU policy.

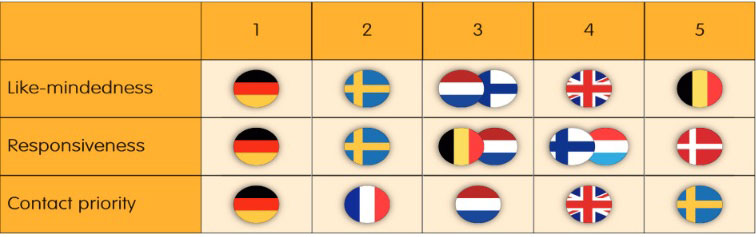

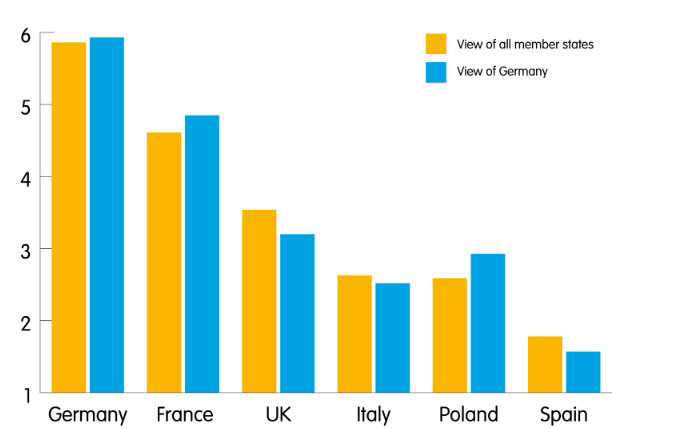

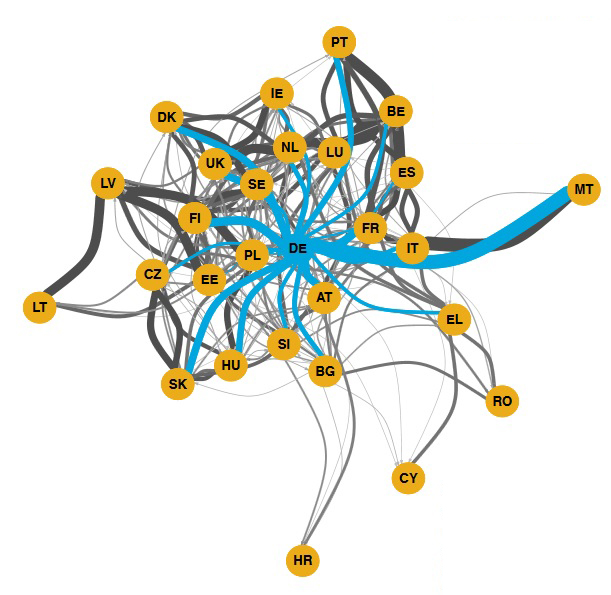

In summer 2015, ECFR conducted a survey of experts and policymakers across the EU member states, and found that political elites in all states agree that Germany is the most influential member state.1 This view was also shared by German participants. The survey found that most member states would generally contact Germany first and/or most on EU affairs. Interestingly, while non-German experts and policymakers ranked Germany as the most influential on foreign policy, security, and defence, German participants ranked France top in this regard. Interlocutors from Europe were less anxious about German power, and more concerned about the growth of nationalist parties across Europe, and worried “that Germany will become like us” in the sense of prioritising its national interests over the country’s traditional integrationism.

But while its EU partners acknowledge German power, the question remains of whether they think that it benefits the European interest as a whole. There is another story about German power, and one that is less likely to be openly articulated by other governments – the story of frustration over German dominance. Research for this paper found that though governments across Europe state that they feel the need to engage with this crucial gatekeeper, they tend not to articulate the impact that German power has had on their own clout within the EU, particularly in the presence of German officials.

Our research found that the European countries’ lack of will to support Germany by sharing the burden of the refugee crisis was influenced by the experience of being at the receiving end of German dominance during the euro crisis. Even a country as powerful as France was scarred by the display of German power. Berlin’s need for help with the refugee issue was seen as an opportunity to redress the asymmetric power balance between Germany and the rest of the Union.

The impact of German power on the rest of the EU is a question that remains underexplored. But it is clear that a number of EU member states have started to think about finding better ways to influence Berlin’s policy machinery and some have centred their EU strategies around Germany. Europeans are investing in better understanding and reading the German political elite, and governments, as well as actors in the worlds of finance, business, and the media, have beefed up their analysis of German policymaking and their presence in the country.

In Berlin, there is a sense that the German political elite is slightly overwhelmed by this degree of interest and expectation, though in interviews many in government accept their high ranking in ECFR’s scorecard as accurate.

Berlin political actors are still learning what German power means, which includes dealing with the experience of being misunderstood or disliked by others for their perceived dominance – something which remains particularly difficult for Germans to take.

In sum, both Germany and the rest of the EU are still adapting to Berlin’s dominance – and the question of what this means for the EU and its other members is yet to be answered.

The EU and the world through German eyes

In the past few years, there have been big shifts in how the German political class view EU politics, the neighbourhood, and the world at large. While the dominant narrative since the fall of the Berlin Wall has been about opportunities rather than threats, things look different in 2016. There is a sense in Berlin that the negative side of globalisation has hit Europe, and that there is spreading disorder, not only in global governance but on the European continent itself. The EU’s neighbourhood has become a source of conflict, with a direct impact on cohesion both between EU governments and within European societies.

In Berlin, discussions on the process of drafting the EU’s new Global Strategy paper are starkly different to those that took place just over a decade ago, when the European Security Strategy of 2003 was drafted. The opening remarks of this document read like a relic of days long passed: “Europe has never been so prosperous, so secure nor so free.” It was a time to deliberate over the Union’s purposes and institutional structure; debates that successive German governments engaged in energetically during the 1990s and early 2000s. At the time, much of Germany’s leadership in the EU was about shaping its legal and institutional framework.

The situation now could hardly be more different. Today, challenges from both outside and within the Union require the capacity to act quickly and decisively, often without a clear institutional framework. Increasingly, action is needed in the area of security and defence, where Germany and the EU as a whole have traditionally been less engaged. And while the challenges faced by the EU and its members in preserving European security and prosperity have grown, to Berlin’s policymakers the Union looks weaker than ever before. Europe’s other strongest powers – France and the United Kingdom – have lost clout, and the United States increasingly expects Europeans to sort out their own business, as it shifts its attention to other global hotspots.

The UK’s vote to leave the Union in June 2016 sent shockwaves through Germany and made Berlin worry even more about centrifugal forces within the Union. The EU looks much more fragmented to Berlin than at any time since the Treaty of Rome was signed nearly 60 years ago. Traditional constructive coalitions among member states that come together to shape European policy – like the informal group of the six founding members – have disappeared or weakened. New coalitions have either failed to emerge, proved unsustainable, or focused on blocking policies rather than creating them. They have failed to provide leadership in the sense of pulling members together or creating consensus. The cooling off of Polish-German relations, and the opposition of the Visegrád Group – the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia – to refugee relocations are cases in point.

Contrary to its expectations, Germany did not find reliable and committed partners with the accession of Austria, Finland, and Sweden in 1995, or Eastern European countries in 2004. Concerns that Germany would attain supremacy by way of enlargement have been proven wrong. The relationship with France remains the only continuous coalition for Germany’s EU policy – and the state of this alliance reaffirms the belief in Berlin policy circles that Germany is alone at the helm.

In this context, Germany has come to compensate for weak leadership from the European Commission and the high representative. Germany has traditionally placed its faith in the power of institutions to tame German power, both for its own benefit and that of the EU as a whole – Berlin knows that its power arouses suspicion and resentment from its neighbours.

Ironically, the country has become one of the drivers undermining the EU’s original structures by increasingly using its weight to veto decisions, and at times acting unilaterally. The German government remains committed to the EU as an umbrella under which European countries cooperate to strengthen security and prosperity. But even in Germany this argument has been more difficult to make lately.

By all measures, 2016 has already been a challenging year for Germany’s political leaders – one in which the most important domestic issues are closely linked to foreign policy. Berlin’s policymakers are worried that spreading disorder in the international system could be replicated within the structures of the EU and the country itself. The connections between Germany’s domestic and foreign policy have never been as strong as they are now. The fact that Germans will suffer the effects of conflicts elsewhere is no longer just a possibility, but has become a certainty in the form of refugee inflows. For this reason, German politicians are considering foreign policy alongside the pressures of domestic politics. The fast-moving debate on the link between the two is crucially important, especially with federal elections due in September 2017.

Rising to the leadership challenge

Three policy areas in particular deserve a closer look in an analysis of German leadership in 2016: the EU–Turkey refugee deal, transatlantic relations, and European security.

The refugee crisis

From Berlin’s perspective, the refugee crisis was of a different order to the confrontation with Moscow over Ukraine, or Greece’s eurozone membership. While Ukraine and Greece affected vital German interests, neither rallied the German public to the extent that the refugee crisis did.

In the months before the EU–Turkey refugee deal, the pressure on the European system and the worst-affected countries grew by the day. Merkel’s authority in Europe tangibly weakened as Germany was unable to ensure EU-wide implementation of the decisions it had pushed for. Very few member states openly opposed the Commission’s proposals on refugee relocations, reception centres, and a stronger EU border agency (Frontex), all firmly backed by Berlin. However, many showed little interest in swift implementation of these decisions. Merkel’s following in the EU began to crumble even among the countries most affected by migration flows, including those that refugees transited through.

In the end, Germany’s backers were reduced to Sweden, Austria, the European Commission, and the Luxembourg EU Presidency. At the beginning of 2016, following Sweden’s and Austria’s shift to a tougher policy on refugees, the support group effectively shrunk to just the EU institutions and the Dutch Presidency of the Council. Furthermore, with France paralysed by the rise of the nationalist Front National party, and Poland abandoning its position in the political centre of the EU to make a shift to the right, the two most reliable bilateral partners of Germany’s EU policy failed to deliver on the refugee crisis. At no time since the fall of the Berlin Wall had Germany been as isolated in the EU as it was in spring 2016.

Berlin knew that if it went down the same path as Sweden and Austria, restricting the entry of asylum seekers, the impact on the Schengen system of passport-free movement would be even more devastating. Merkel did not want to bury Schengen, and nor did Berlin want to further destabilise Greece, where thousands of refugees were stranded after the closure of the western Balkan route. In its determination to preserve the fundamental pillars of European integration, Berlin allied with the European Commission to pursue a solution to protect Schengen. But the situation in Germany was becoming increasingly difficult to handle, and time was an important factor for Merkel, with elections in three German states in March 2016, and polls indicating an alarming uptick in support for the nationalist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party. In early spring 2016, the talk in Berlin’s political circles, and among the public, was all about “bringing down the numbers of refugees”.

Germany’s domestic situation was clearly the major driving force behind Merkel’s actions on the Turkey deal. The hope was that the agreement would have a quick impact on the numbers arriving on the Greek islands. From a German perspective, the deal has worked so far, and has patched up tensions within Europe for the time being.

What does the negotiation of the EU–Turkey refugee deal tell us about Germany’s leadership approach? On the one hand, Merkel worked to bring the whole of the EU together to deal with the refugee challenge. The chancellor believed in Europe’s humanitarian responsibility to help refugees and invested in protecting the European interest as a whole – ensuring the survival of the EU’s migration scheme, and promoting European solidarity with Greece.

On the other hand, some EU member states pointed out that Berlin was responsible for dealing with the refugee challenge, after unilaterally suspending the Dublin system – under which refugees must seek asylum in the first EU country that they arrive in – and failing to consult with the rest of the EU. This limited Germany’s ability to forge a common European coalition.

When its inclusive approach failed, Berlin built a coalition of European countries of transit and/or destination, but still insisted on an overall EU burden-sharing mechanism and kept the European Commission and the EU Presidency on board. Under increasing domestic pressure, Merkel went into realpolitik mode once Turkey had been identified as the key to slowing the numbers of arrivals to the Greek islands. By this point, the coalition of fellow Europeans had disintegrated – the European Commission and the Dutch EU Presidency were still on board, but ultimately this was a deal that Germany needed more than anyone else.

The stark contrast between Berlin’s humanitarian arguments on the one hand, i.e. the obligations of the 1951 Refugee Convention, and its realpolitik approach to Turkey on the other hand, create a tension that Germany has yet to explain to its European partners. How far is Germany willing to go when its vital interests are at stake? To what extent is Germany willing to take risks that may alienate its EU partners?

If the deal continues to deliver on its promise to “end the migration crisis in Europe”, the EU will likely attribute its success to Merkel’s leadership. But if it fails, for whatever reason, the tables will turn and the German chancellor will own the failure. She will also have to face wider collateral damage, such as the EU’s dependency on Turkey at a time when Ankara is set on an autocratic path. The chancellor will also have to deal with the shift in the framework of the EU Turkey conversation. This had previously taken place within the EU’s enlargement policy, led by the European Commission and the European External Action Service. Now, Germany has pushed it towards an increasingly intergovernmental structure, where national governments engage directly with Ankara, rather than going via EU institutions. Finally, Berlin will have to face the criticism that Germany used European institutions to pursue its national interests, undermining its claim to represent the interests of the EU as a whole.

From these events, Berlin has learned that its influence will suffer if Europe is weak and divided. Germany’s political class continues to see the EU as the best available framework for the articulation of its national interest. But a strong and capable Germany, as the Foreign Ministry’s policy review concluded in 2014, requires a strong and likeminded EU. In the words of Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, “(we) must enable Europe to benefit from our strength, for we benefit from Europe’s strength”.2 As a result, the EU’s inability to collectively deal with the impact of the refugee crisis has been viewed with unease in Berlin.

The EU’s failure to implement its policy on the refugee crisis weakened its ability to amplify Germany’s position when it came to making a deal with Turkey. For Germany, this means preparing for a stronger national role, which implies costs and risks. The changing nature of decision making, from consensus to intergovernmental coalitions of majorities, allows Germany to have a strong influence on decisions, but at the same time entails the risk of German dominance. This could ultimately lead to other EU members hedging against German power rather than focusing on developing joint European responses.

Transatlantic relations

If President Barack Obama’s visit to the UK and Germany in April 2016 confirmed anything, it was the extent to which US political elites worry about the strength and unity of Europe, and how much the president looks to Berlin to sort things out. Lack of consensus and a waning sense of shared purpose, undercurrents of political rivalry, and the growing impact of identity politics are all weakening the EU and causing concern on the other side of the Atlantic. The UK’s plunge into domestic turmoil following the Brexit vote will heighten Washington’s concerns about the future of the EU.

Washington’s political circles have limited appreciation for EU-style supra-nationalism. Instead, Americans want Europe to come together in order to settle the “European question”, i.e. to take responsibility for ensuring that the bloody twentieth century is not followed by yet more crises, wars, and unrest on the European continent. Obama expects Merkel to take the lead in the EU, not only in terms of building internal cohesion, but also on foreign policy. The chancellor has welcomed the attention, but has shied away from accepting some of Obama’s farther-reaching suggestions. This includes the idea that Germany could be Europe’s benevolent hegemon, shelling out the resources needed to support such a role. Merkel prefers to lead through rules and processes. She has been disappointed by messages from the US that signal unwillingness to respect the rules and constraints of EU policymaking.

When the sovereign debt crisis challenged her determination to hold the EU together, voices from the US, including within government, criticised Merkel’s approach as “austerity”. These criticisms failed to take into account the political and legal context of the European monetary union. US proposals for how Germany should bail out Greece reflected a lack of understanding of and support for what Merkel saw as her task – upholding the rules upon which integration was built. From the chancellor’s perspective, her US partners did not understand or share her motives and goals throughout the entire debt crisis.

US-German dynamics over the war in Ukraine are a further demonstration that the German government is increasingly willing to take risks. In early 2015, as fighting in eastern Ukraine escalated, Merkel felt pressure to act from the US. She risked failure in an attempt to bring Ukrainians and Russians to the table. At the same time, in Washington, members of Congress and pundits were debating whether to arm Ukraine. Merkel lacked the full support of the US president in her attempt to bring about a negotiated solution.

This pushed Berlin to mobilise further European resources and take greater ownership of the crisis themselves. The clout of the Franco-German team was crucial in this regard. Had President François Hollande and Merkel failed in Minsk, the West’s Ukraine policy would have been defined in Washington (and London), and the consensus within the EU over sanctions against Russia would likely have been lost. German leadership, alongside that of the French, has been instrumental in clearing the way for a European approach to dealing with Russia and the war in Ukraine. Contrary to the common narrative that Berlin and Paris can no longer pull along the EU as a whole, the Franco-German alliance has become a positive influence on European foreign policy in recent years. While French weakness continues to be a stumbling block to successful eurozone reform, German reluctance had been the major obstacle to strengthened foreign and security policy. But now, with Germany demonstrating a credible will for leadership, this cooperation has the chance to unleash its full potential. And Berlin knows that, now that the United Kingdom has voted to leave the EU, it will be put even more on the spot.

Franco-German leadership in foreign policy comes with a risk for Berlin - that other member states will feel excluded. This is particularly clear in dealing with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who has no appetite for the EU’s notion of shared institutionalised power, and prefers to deal with Europe’s strongest countries and leaders individually – to play “big country politics”. This can alienate other member states.

For Berlin, the more inclusive EU system is worth protecting, because it allows Germany to play a strong role in Europe, as other countries find it a more acceptable mode of German leadership. German officials frequently emphasise that the type of leadership they have been exercising in the intergovernmental setting with Paris and other capitals lately is one that brings the EU institutional dimension to the table, often to the frustration of Moscow.

Americans do not care much about these internal European discussions so long as Europe delivers strong policy responses. But, for Germany, the return of big power politics to Europe is likely to bring the German question even more to the fore – which runs the risk of stirring resentments and ultimately weakening Berlin’s ability to lead. Washington should read Germany’s continued commitment to sharing foreign policy responsibility with EU institutions not as a product of its reluctance to lead, but as a sign that it wants to lead, and sees this as the best way to do it. Washington will not back down from its expectation that Europe, and Germany, own these recent and future challenges to European security. It is for Berlin to show that it cannot only engage in intellectual and diplomatic leadership, but that it will also address the need to bring greater military resources to the table

European Security

The ring of fire around Europe – in the form of conflicts in its neighbourhood – has sparked a vigorous debate in Germany on how best to respond.3 Berlin is investing a great deal in finding diplomatic solutions to the wars and crises surrounding Europe. The government has also taken further steps in security and defence, an area where its partners’ expectations have been particularly high. The Defence Ministry is well aware that its new white paper on security policy and the future of the armed forces will be dissected in and around Europe.

Berlin also gave a robust response to the French invocation of the EU Treaty’s mutual defence clause, Article 42.7, after the November 2015 terror attacks in Paris. Berlin is lending considerable support to its allies’ air strikes in Syria, by German standards, and has extended the mandate of German troops deployed on the UN mission in Mali.

The federal government is planning to increase the defence budget by 6.8 percent in 2017 and the armed forces are in a process of transformation, after the end of conscription in 2011, to make it a more professional body that is capable of responding to new and traditional forms of warfare. Berlin is among the leading nations in implementing the agenda of the 2014 NATO summit – perhaps to the surprise of its European partners – and has been proactive in handling its divergences in interests from the new Polish government ahead of the July 2016 NATO summit in Warsaw. Differences in views over the structure of a military presence to secure NATO’S eastern flank persist between Berlin on the one hand, and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Baltic states on the other. But the key case that Germany has made at the Warsaw summit is that it is investing in defence and seriously considering playing a more active role in this sphere.

However, the reality is that there is a major gap between security and defence measures that the federal government may adopt in the months ahead, and the views of German society. With general elections scheduled for autumn 2017, the federal government has been working towards a narrative that brings together foreign, security, and development policies. Germans are not unaffected by security threats and other developments overseas. Both the terrorist attacks in Europe and the large number of refugees and migrants coming to Germany have caused worldviews to shift.

In Germany, there is growing public recognition that the country is a major stakeholder in the future European security order. But is the pacifist German public willing to accept a government that is ready to wage war in order to defend the security order that they have so greatly benefitted from? The US-led security policy in the Middle East over recent decades has not been convincing to many Germans, who consider that it failed to ensure security, and it will be vital for European member states to develop a collective approach to security in order to win over German public opinion in the medium to long term.

Common European security is an area where intellectual leadership is needed, and where Germany can play a bigger role. Berlin has become less ideologically concerned with the debate over whether this should be via NATO or via the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Instead, it has been pushing pragmatically in favour of using all available instruments to strengthen European security in the framework of the EU, NATO, and the OSCE. Germany holds the OSCE presidency in 2016, and can make the most of this opportunity by building support for burden-sharing with other EU member states. Again, it will be vital that Paris and Berlin come to a joint understanding of their complementary roles in this period.

The future of German leadership in the EU

There is no doubt that Germany’s capacity to lead is strong, and the data from ECFR’s survey supports the claim that Germany has significant ability to influence and lead member states from all regions of Europe.4 The stakes are high, and Berlin will have to fight to keep the EU together in the face of significant anti-EU sentiment in several member states, including in Germany itself. Because the consensus between the group of “core” member states is weak, Germany will need to instead focus on deepening integration in specific policy areas across a larger group of member states.

In her 2015 speech at the Munich Security Conference, von der Leyen put forward the notion of “leading from the centre”, envisioning a Germany whose contributions to European security are firmly embedded in its collaboration with partners. This concept is based in consensus, and opposed to the idea of Germany ultimately becoming a US-type hegemon on the European continent, using its strength to go it alone when necessary.

But where does the EU’s political centre lie? The definition of the political centre put forward in this paper is broad and has a political aspect, but lies beyond the divide between the left and right wings. In this understanding, the centre is a place of constructed consensus where a number of member states come together on an ad hoc basis, or in longer-term coalitions, to build public support for common European solutions across a range of policy areas. This view of a centre made up of flexible coalitions is less static or rigid than the concept of a consensus within “core Europe” – i.e. a set number of countries, most likely the eurozone members. It will require a stronger commitment to the process of building coalitions between member states. This concept of Europe’s political centre takes into account the views of domestic audiences within member states, rather than simply focusing building alliances between governments. In this, it differs from the traditional view of EU coalition-building, which paid little notice to public opinion, and was conducted by diplomats rather than politicians.

Germany is well-placed to engage in such leadership by proactively building a “centre” for EU policymaking. It has the resources to do so, and benefits greatly from embedding its power in the EU setting. Such coalitions will allow German and European interests to meet more organically than under the intergovernmentalism by default that the EU has been operating with during the crises of recent years, and that has often raised suspicion about German power.

Recommendations for Germany

- Germany’s top politicians should more openly address the opportunities and challenges of German power within the EU. Berlin should be proactive in explaining to its partners how it thinks German power can best serve the EU as a whole, and leave no doubt about Germany’s continued commitment to the EU. Germany would also benefit from openly reflecting on where and why German dominance has harmed the Union in recent years – though this is unlikely to be articulated by German leaders.

- Coalitions are vital if Germany is to be a successful leader in the EU. Berlin needs to build a more structured process of coalition building. The German political class may disagree, but they would be surprised about the responsiveness they would find if they began to reach out more seriously and more consistently to their EU partners.

- In particular, it is worth exploring the potential of a coalition with the affluent, small member states: namely the Nordic countries, Benelux, and Austria. They represent an important part of the EU’s economy and its financial resources; their quality of governance is generally high, and their foreign policy outlook corresponds well with that of Germany. These countries are geographically close to Germany, share many of the same preferences, and, according to the data of the coalition survey, want to work with Berlin.5 It is vital, however, for Germany to understand the domestic setting in these member states and make a realistic assessment of what can be achieved together. Sectoral deepening will be more difficult with countries that face domestic resistance to the idea of an ever closer union – for instance in the Netherlands and Denmark – but it will still work with others. There should be a more pragmatic understanding of what it means to work together for the greater European good – one that does not always have to lead to deepening integration or institutional change.

- Franco-German cooperation remains a key pillar of Germany’s place in the EU. This is self-evident for German policymakers, but more can be done to make this partnership flourish, especially in foreign and security policy. The paper produced by Foreign Ministers Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Jean-Marc Ayrault in response to the UK referendum is a good start,6 but its suggested initiatives need to be followed up. Investing in understanding each other’s outlook on the world has to go beyond day-to-day business and include a strategic conversation on the conflicts surrounding the EU and its neighbourhood. It must also include discussion of the instruments available both within the EU and NATO to respond to these security challenges. Now that the UK has voted in favour of leaving the EU, Berlin and Paris will also need a plan for how to continue to integrate the UK into European security structures.

- Looking inward, Germany should explore how it can strengthen capacity in core ministries. A number of EU countries have developed strategies to engage with Berlin and started to strengthen their outreach in the German capital. The administration needs to be ready to respond to this growing interest in Berlin. Capacity for policy analysis will also have to be strengthened. This has a public affairs dimension, too, and German policymakers should talk even more strategically to those who are in the media and think-tank business, lest they talk about Berlin on their own terms.

- German governments will also have to prepare to foot the bill more often in the overall interest of the Union and build constituencies around that at home. They will also have to address the difficult prospect of human lives being lost in the wider European interest, with a stronger engagement in security policy. While the debate on a stronger German role in foreign policy has come quite a long way already, the debate on security has not, and is very likely to bring to the fore fundamental controversies within German society at large that policymakers have to be prepared for.

- Germans need to mentally prepare for conflict, which will continue to be a regular feature of discussions and decision-making within the EU. For historic reasons, it is particularly difficult for Germans not to be liked by others, but this is at times unavoidable in any relationship. Ultimately, the fruits of German leadership should speak for themselves.

- While leading will look messy, involving intergovernmental solutions and ad hoc coalitions rather than clear-cut homogeneous European solutions, the least worst options have to be pursued. Berlin should continue investing in European institutions to mitigate German dominance. The EU’s institutions will only maintain their legitimacy and strength if they are credible partners for Germany’s leadership strategy.

Germany’s Partners

Berlin’s partners in the EU will have to decide how to deal with Germany’s strength. It won’t go away any time soon, and it won't be balanced in the ways it was before unification in 1990, when Germany was junior to France and constrained by its dependence on integration. What’s more, it would not be in Europe’s interests for Germany’s strength to wane, as then-Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorsky pointed out in a pivotal 2011 speech in Berlin. Seeking to counterbalance Germany’s weight would simply lead to deadlock and stagnation in the EU. The interests of member states as a whole would be better served if the ambitions of large member states – not just Germany – had greater traction. Otherwise, powerful countries such as Germany or France might turn away from the EU.

Merkel has no appetite for unilateral leadership, and nor will her successors. Anything that appears to be hegemony, even if qualified by the adjectives “reluctant” or “benevolent”, repels the German political class. More than other large actors, German leaders feel the need to act within a consensus. They want coalition partners who share their preferences, burdens, and responsibilities. France’s EU policy is based on the principle of acting in concert with Germany, and Italy seems to be moving back to a similar position. Spain could also be considered as sympathetic. Poland’s interests would be better served by a close relationship with Germany, but the worldview of its current leadership stands in the way. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that the Visegrád Group will move closer to the EU’s political centre in the coming years.

Germany’s interests would be better served by working more closely and building coalitions with the smaller, affluent member states. Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Austria represent a combined population, GDP, and contribution to the EU budget comparable to that of France. Traditionally, Germany has worked closely with these countries, listening to and representing their views. They have strong relationships with Germany on a range of policies, from the environment to R&D, industrial policy and trade, fiscal matters, social policy, and labour relations. But what has been neglected over the past decade is cooperation on the strategic level of managing the EU.

For the rest of Europe, renewing this political core of committed member states is the best way to respond to Germany’s changing role. It will keep the EU at the centre of German ambitions, give leverage to states that engage with Germany, and oblige all states to reflect the European interest in their plans.

Too often, power in the EU means veto power, the ability to prevent action rather than to shape it. Many member states have a degree of veto power, though few have much. By contrast, the constructive power to shape outcomes and move Europe ahead is in short supply. No state, not even Germany, has that power alone; it requires a strong coalition that can reach different political groupings of member states. Building this type of consensus is the key to answering the “German question”.

Notes

1 For data and analysis, country breakdowns, and comparisons, see “Rethink: EU28 survey”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 6 June 2016, available at external pagehttp://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_rethink_europe_eu28_surveycall_made (hereafter, “Rethink: EU28 survey”).

2 See the results document, “Review 2014 – A Fresh Look at Foreign Policy”, German Federal Foreign Office, available at external pagehttp://www.auswaertigesamt.de/cae/servlet/contentblob/699442/publicationFile/202986/Schlussbericht.pdfcall_made; quote taken from the foreign minister’s conclusions, p. 11

3 See, for example, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, “Germany’s New Global Role – Berlin steps up”, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2016, available at external pagehttp://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/EN/Infoservice/Presse/Interview/2016/160615_Namensartikel_ForeignAffairs.html.call_made

4 For a visualisation, see the graphs in the “Power” chapter of the “Rethink: EU28 survey”, available at external pagehttp://www.ecfr.eu/page//RethinkEurope_EU28_survey_2015_analysis_and_results_June16.pdfcall_made, in particular slides 28–31.

5 See “Rethink: EU28 survey”, slides 83–88.

6 See Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Jean-Marc Ayrault, “A strong Europe in a world of uncertainties”, press release, 24 June 2016, available at external pagehttp://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/EN/Infoservice/Presse/Meldungen/2016/160624-BM-AM-FRA.htmlcall_made.

About the Authors

Josef Janning and Almut Möller are senior policy fellows and jointly head ECFR’s Berlin office.