How the West shaped China's hidden battle of ideas

- Published

A battle of ideas is under way in China before a Communist Party Congress in the autumn that will appoint a new generation of leaders. For outsiders, it is strikingly familiar - Left v Right. That's because while China exports just about everything else, it still imports policy ideas.

"I'm Zhang Jian," says one of China's bright young political scientists. Then he glances over at me and realises, with a look of sympathy, that as a foreigner I may not be well versed in Chinese.

So he quickly adds: "In the Western way, maybe I should say Jian Zhang." He shrugs. "Either is fine for me."

Prof Zhang Jian (Zhang, his surname, is given first in the Chinese naming style) is not only fluent in the English language, he is also fluent in Western culture, ideas and history. He spent six years studying at the elite Columbia University in New York City, before taking up his post at Peking University's prestigious School of Government.

He is not alone. For mainland Chinese intellectuals, the journey to the West - and then back to Communist China - is now a well-trodden path.

In fact, the main schools of intellectual thought in China have one thing in common - their leading thinkers have often spent time in Western universities.

That means that for Westerners, who may struggle with China's very different language or food, Chinese policy debates are split along strikingly familiar lines.

Zhang counts himself on the classically liberal "right" wing. He supports free markets and political reform.

"I would love to see the country become more similar in its general system to that of the UK or United States," he says.

This camp - sometimes called China's New Right - have been most successful in economics. They influenced China's liberalisation in the 1980s and since.

"They often studied economics in places like Chicago or Oxford University," says Mark Leonard of the European Council on Foreign Relations, author of What does China think?

"They came of age in the 1980s, a time when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister in the UK, Ronald Reagan in the United States, and they became firm believers in the power of the market."

Zhang Jian is younger than many of his liberal peers, in his 30s, but he first read Western free-market gurus like Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Karl Popper as an enthusiastic teenager - before he even got to the West.

"Translations of their work used to sell out in China," he recalls.

But in the last few years, a rival camp to this free-market, right-leaning set of intellectuals has emerged - again, after being educated in the West.

China's "New Left" doesn't reject free markets completely, but argues for a stronger socialist state.

Many of them ended up in the West after being caught up in China's student demonstrations of the late 1980s.

"One of these figures, a young researcher who was then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called Cui Zhiyuan, wrote a path-breaking article," explains Mark Leonard.

Now a professor at Tsinghua University, Cui argued that China should liberate itself from neo-liberal economics. It was written in the late 1990s just as anti-globalisation movements were beginning in the West, too.

Other leading lights on the "New Left" include Prof Wang Hui, who was once a factory worker who went on to study at Harvard University.

Rather than being impressed by how the West worked, these new writers were often disenchanted after seeing it for themselves.

The large numbers of Chinese students abroad today tend to have a "more nuanced" view of American style capitalism and democracy than they did in the 1980s, says Prof Daniel Bell, at Tsinghua University - a professor of philosophy from Canada who has spent many years in China and is close to New Left thinkers.

He says the invasion of Iraq, and the financial crash, have strengthened the hand of China's New Left: "Iraq… led to fairly extreme cynical views not just among intellectuals but I think also among ordinary citizens," he says.

The scholars labeleld New Left often reject the notion that China should follow a similar path to the West as it develops. The Palestinian-American historian Edward Said - and his criticism of "Orientalism," the way the history of the East and its people was presented to serve the interests of the colonial West - has been influential.

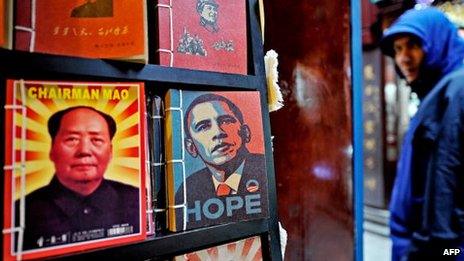

The revival of left-wing ideas was particularly noticeable at the inland city of Chongqing - where until recently the charismatic official Bo Xilai was in charge. After he was suspended earlier this year, over the alleged murder of a British businessman, he was widely criticised for going too far to the left - overseeing, for example, a public revival of Chairman Mao and Maoist rhetoric.

But disenchantment with Western democracy is also leading to a wider "revival of tradition" amongst Chinese intellectuals, Bell says.

Prof Pan Wei, a superstar on China's lecture circuit, argues that the country should not embrace Western-style democracy. Instead the One Party state, which has adopted old Chinese imperial traditions like meritocratic exams for officials, is more appropriate, he says.

"It's the Chinese system," says Pan. "It's a very sophisticated system."

Pan teaches at Peking University but earned his PhD at another of America's leading institutions - Berkeley, University of California.

Bell traces the arrival of Western political ideas in China back to the early 20th Century, when China was under colonial domination.

Bo Xilai, a senior Chinese politician, has been accused of tapping the phones of Communist party leaders

"China was viewed as a relatively undeveloped and poor country and most intellectuals and reformers tended to blame China's own tradition for its so-called backwardness," he says. "So you had people who looked to liberalism and to Marxism and to anarchism."

"Of course it was the Marxists that ended up winning the debate," he says. The Chinese Communist Party, inspired partly by Marx's writings, created the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Zhang, the liberal who studied at Columbia University in New York City, says he was always aware that he was on a well-worn path to the West.

He mentions Prof Hu Shih - who studied at Columbia 100 years ago and then returned to Peking University - as a "standard bearer" for Chinese liberalism.

So does the increasing number of vocal, Western-educated intellectuals in today's China mean that political debate between left and right will be more open after the country's leadership changes?

It is hard to say because the current atmosphere in Beijing currently is far from liberal. In the wake of Bo Xilai's sacking, the country's colourful on-line discussion about ideas has been muted as many websites have been blocked. Leading webmasters were afraid to meet me.

Zhang worries that liberal reform may in fact be stalled.

"I would say I personally do not foresee any significant change in the way that they do politics in this country," he says.

"I think they are going to increase what they call 'social management'. The old term for that is 'stability maintenance', right? A very hi-tech controlled state."

Listen to the full report on Analysis on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, 9 July at 20:30 BST or Sunday, 15 July at 21:30 BST.