The voting dead: Why electoral fraud in Bosnia should matter to the EU

Voter fraud and voter intimidation appear in many forms in Bosnia, and are becoming especially visible ahead of upcoming local elections in November

There is an old joke in the United States that politicians want to be buried in Chicago so that they can remain active in politics after they die. A similar joke could be told about Bosnia and Herzegovina, some of whose citizens have lately been learning that their dead ancestors are preparing to vote in the local elections scheduled for next month. Such was the story of one man who found out that his deceased mother, who lived and died in Canada, was registered to cast an absentee ballot from Serbia. The “voting dead” are not the only examples of falsified registration: a candidate for a municipal council in the municipality of Teslić in Republika Srpska found out by accident that he was registered to vote by mail from Serbia – a country he has never lived in. So, as they arrive at polling stations on election day, some voters in Bosnia and Herzegovina may encounter their dead ancestors, so to speak.

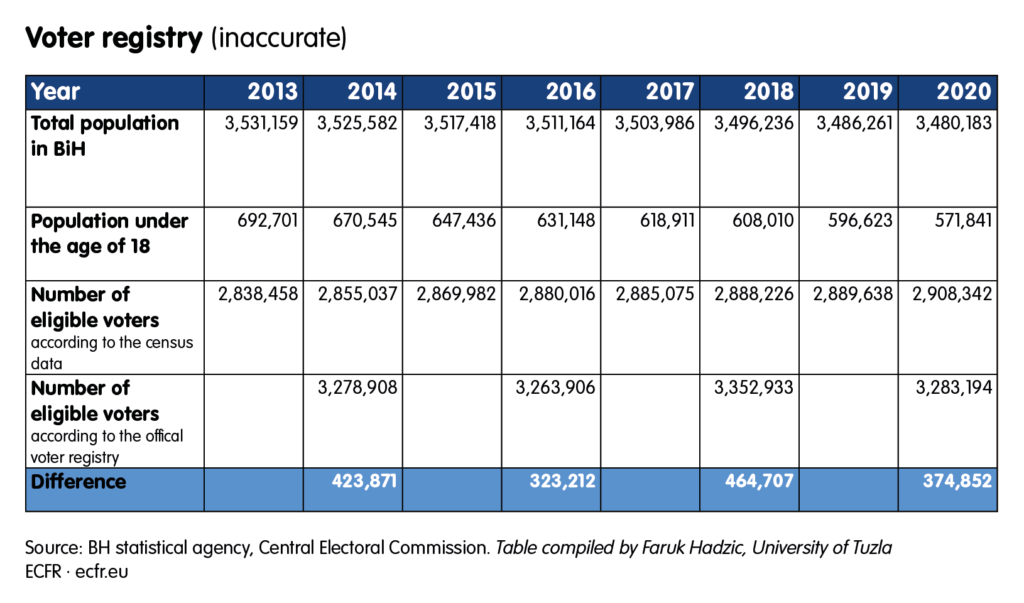

Voter fraud and voter intimidation take many forms in Bosnia, but it is worth examining two particular tricks. Firstly, and as noted, is populating the electoral roll with the deceased. The central electoral roll in Bosnia is inaccurate and provides ample opportunities for voter fraud. For the 2020 election, 3,283,194 names are registered on the list issued by the Central Election Commission. Yet, according to the census data adjusted for births and deaths from 2013 until 2020, the number of Bosnian citizens aged over 18 is just 2,908,432. Even taking into account registered diaspora voters, who number 101,771, the number of registered voters is still over 270,000 higher than the number of eligible voters according to the census. A discrepancy of a quarter of a million in a country of 3.5 million people provides ample space to manipulate votes and swing an election.

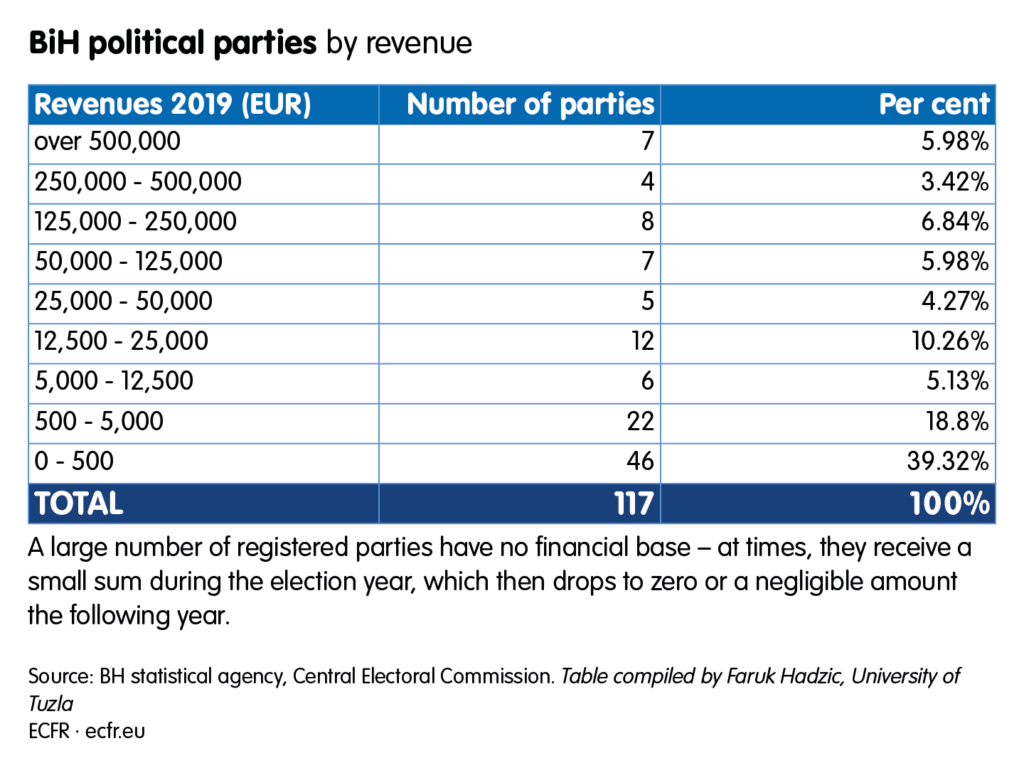

The second trick is to set up fictional political parties. A large number of parties and politicians were registered for the 2018 general election in Bosnia: 123, to be precise. And yet the majority of these parties have never been heard of by voters, since they do not seem to play a conventional role in the election process – that of competing for votes in an election campaign. Rather, they seem interested in gaining seats on the boards that oversee polling stations. Why? In order to secure votes for the larger incumbent parties on whose behalf they seem to exist. The oversight boards are key to counting votes and the official appointment process for these bodies is based on seat balance between all political parties participating in the elections. Fictional parties disturb this balance by trading or selling their seats on the boards and in this way facilitate dominance by incumbent parties over the polling stations. In 2018, a large number of members of the oversight committees were changed the night before the election, which led to a public outcry and widespread suspicions of vote rigging.

An EU problem

This problem should be of high concern for the European Union, which has made free and fair elections its top priority in the European Commission’s Opinion on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s application for EU membership. Brussels and the EU member states interested in preventing further democratic backsliding in the Western Balkans know that this cannot be achieved without securing free – and also fair – election processes. The 2016 election in North Macedonia is a case in point. During 2015 and 2016, the EU and the United States cooperated closely on ensuring that the conditions for a free and fair election were established in North Macedonia. In this way they laid the groundwork for the conditions that led up to the Prespa Agreement with Greece on the name of the country, and for the reversal of the state capture in North Macedonia.

As they arrive at polling stations on election day, some voters in Bosnia and Herzegovina may encounter their dead ancestors, so to speak.

Bosnia is an immediate concern because its local elections are happening soon. These are clearly not a general election and, even if it were, Bosnia’s fragmented electoral system makes a North Macedonian scenario of democratic regime change difficult, if not impossible. But this is precisely why the local elections are so important. Given that the current electoral system favours ethno-nationalist parties, reversing state capture in Bosnia will have to begin as a bottom-up process, with reformist mayors or cantonal officials acting as agents of change. Besides the two Federation candidates for the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mayors are the only executive functions in Bosnia directly elected by citizens without having an ethnically defined role. Mayors are the closest to citizens and have the greatest incentives to deliver. Their direct link with local communities therefore often results in both greater accountability and more visible progress on governance and the economy. As such, these elections are the only source of hope in Bosnia’s otherwise gloomy political and economic situation which has been driving the mass exodus of its citizens.

What the West can do

Voter fraud is just one part of the much larger challenge of bringing the country’s electoral system into line with European standards, which will also need to include addressing the Sejdic-Finci ruling of the European Court of Human Rights and lessening the domination of ethno-nationalist politics: 25 years after the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, Jews and Roma are still not able to stand for the Bosnian presidency.

The long-term goal therefore must be wider electoral and constitutional reform that allows Bosnia to transform from a state captured by ethno-political oligarchs into a functioning multi-ethnic democracy.

Reducing voter fraud is a necessary step in the short and medium term. The problem of fictional voters and vote manipulation will not be solved without cleaning up local electoral rolls, establishing a central registry, and introducing electronic solutions for registration and voting. No effective judicial instruments for redressing voter fraud once it is identified exist in Bosnia so the focus must be on prevention rather than redress.

In the immediate moment there are measures that can make a difference even for the elections next month. A coalition of democratic EU member states, the US, and the United Kingdom should offer support to the Central Electoral Commission to ensure extensive monitoring of the vote count through local NGOs, most notably Pod Lupom. While heavy presence of the diplomatic corps has been announced for December elections in Mostar, the usefulness of sending diplomatic representatives to the polling stations will be judged by their continued presence, as most fraud is reported to take place after the polling is closed.

Similarly, independent monitoring of the transportation of ballots from polling stations to the central counting centre should be ensured by the same NGOs or Western diplomatic missions: anecdotal evidence suggests that most fraud occurs as ballot boxes are moved, where bags containing completed ballots are physically replaced. And, just as importantly, the EU and US should work with the Central Electoral Commission and municipalities to ensure that covid-19 health and safety requirements and protection equipment is in place so that the voters can go to the polls without fear of contracting the virus. Without such precautionary measures, the ratio between real and fictional voters will shift even further towards the latter.

Faruk Hadzic, from the University of Tuzla, has contributed to this article including with data, tables and information on voter registries and fictional party registration.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.