Frozen out: Why the EU needs a strategy on the Arctic

Through a multilateral and cooperative approach to the Arctic, the EU could ensure that projects in the region addressed its economic and environmental concerns

For centuries, the Arctic has been widely perceived as an unspoiled glacial and polar area. But, in recent times, climate change and new technology have triggered developments in the region that could have major implications for maritime trade, energy supply, and geopolitics.

Among the three main passages through the Arctic Ocean, the North Sea Route (NSR) – the one closest to the Russian border – is most likely to become a shortcut between Asia, Europe, and North America. The opening of the route could significantly reduce costs for the shipping industry.

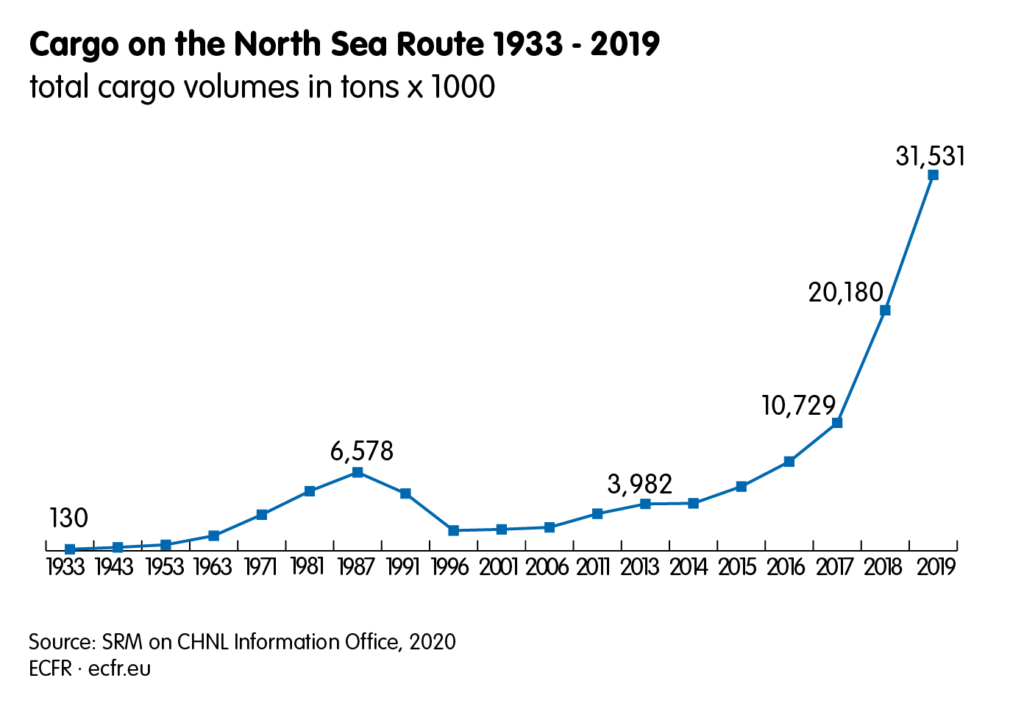

Since the first test of a container ship (a Maersk vessel) along the NSR in 2018, there has been a marked increase in trade along the route. In 2019, ships completed more than 2,000 voyages along the route, transporting 31.5 million tons of goods (see graphic below). The figure is expected to reach 92.6 million tons by 2024.

Many governments now have a real interest in developing the NSR, along with other Arctic routes. But they will first need to answer some key questions about the impact of the NSR on the shipping industry and the maritime economy more broadly.

Climate change and the environment

Climate change and the environmental impact of shipping and energy extraction have major implications for the exploitation of Arctic routes. Global warming is the primary cause of de-icing and, accordingly, the reason why these routes are becoming viable. Climate change has also led to a rise in sea levels.

An increase in naval traffic through the Arctic would involve greater use of fuel-hungry icebreakers and ice-resistant ships – perhaps cancelling out the reduction in carbon emissions that would otherwise result from shipping through shorter northern routes. This may be unpopular with citizens of European countries, many of whom are increasingly sensitive to environmental issues and often demand socially responsible behaviour from shipping carriers, energy firms, banks, and other companies.

These considerations – in terms of both reputation and costs – are likely to limit the use of the Arctic as a transoceanic global shipping route. But it is unclear whether they will also limit local cargo traffic and regional energy exploitation, given that there is a relative lack of political transparency and public opposition in some countries with interests in the region.

In the complex legal framework that covers the Arctic, there is an overlap between international conventions and treaties, and national and local rules.

In addition, in the complex legal framework that covers the Arctic, there is an overlap between international conventions and treaties, and national and local rules. This complexity could create obstacles to business ventures in shipping and energy there.

Energy corridor

It remains to be seen whether the Arctic route will evolve into a maritime energy corridor rather than a global cargo route. Russia, which owns 70 per cent of natural gas and 41 per cent of oil in undiscovered Arctic reserves, is attempting to dominate the region using its logistical advantage. The largest littoral state on the Arctic Ocean, Russia has developed a relatively advanced transport network in the region and has the largest icebreaker fleet in the world. The country has many plans for new energy exploitation projects there. For instance, Russia recently completed its first large-scale gas extraction project in Yamal Peninsula, at a cost of nearly $30.5 billion.

In the coming years, these energy investments are widely expected to boost cargo traffic in the Arctic, collateral maritime transportation services in the region (especially along the NSR), and port infrastructure in Russia. Although there is little evidence that the NSR will soon become an alternative to the Suez canal for Europe-Asia trade, the route could still play an important local and regional role in such commerce.

Covid-19 and geopolitics

Due to its geographical position and abundant energy resources, the Arctic is strategically important to Russia, China, the United States, and the European Union. Yet the global economic crisis caused by covid-19 has had a significant effect on all these key players in the Arctic. The crisis will continue to reduce cargo shipping trade and demand for oil and gas, perhaps limiting their activities in the region – at least for now.

China does not border the Arctic but, as a global power, officially fixed its Arctic policy in a white paper published by the State Council Information Office in January 2018. Since then, it has implemented a complex diplomatic and economic strategy to gain access to the natural resources of the area and to increase its influence there.

In contrast, the US has not become directly economically involved in the Arctic. But the country appears to be mildly committed to containing Russian and Chinese ambitions in the region. For example, US initiatives focus on endorsing freedom of navigation along the NSR, on the upholding sanctions on Russia (that severely hamper its offshore drilling capabilities), and on constant checks on Chinese naval power.

The EU has tried to design a strategy to integrate the NSR into its logistical routes, through the extension of the Scandinavian-Mediterranean and North Sea-Baltic corridors. And, in 2016, the EU reaffirmed its strategic interest in the Arctic in two high-profile documents:

- The Global Strategy, which referred to the importance of limiting tensions in the region.

- The “Integrated EU policy for the Arctic” communication, which specifically addressed European priorities there.

As a whole, the joint provisions of the two documents set out a comprehensive approach that attempts to coordinate diplomatic initiatives with internal EU policies in relation to the new challenges in the Arctic. The EU focused its efforts in sustainable development there on several instruments for funding projects such Horizon 2020 and InnovFin, while channelling key investments through institutions such as the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Under this strategy, two investment areas appear to play a significant role for European maritime trade and logistics in relation to the Arctic: space monitoring and navigation (through the Copernicus and Galileo satellite networks, as well as participation in the GEO Cold Region Initiative) and the Trans-European Transport Network.

Accordingly, Mediterranean countries have a particularly strong interest in developing such a strategy. Unfortunately, despite years of diplomatic efforts, the Arctic Council has not yet recognised the EU as an official observer – due to opposition from both the US and Russia.

The EU’s strategy on the Arctic could develop the NSR initially through energy extraction projects and, later, as a major commercial shipping lane. This approach could lead to a gradual build-up of business ventures in the Arctic – one that relied on international consortia to share the costs and risks of operating there. Through a multilateral and cooperative approach to the Arctic, the EU could ensure that projects in the region addressed its economic and environmental concerns.

It is likely that states (particularly Russia and China) will cooperate in the Arctic in three main areas: scientific research, environmental protection, and port and logistics. In this context, a more proactive EU could make a difference in the region, by playing a balancing role and blending economic development with high environmental protection standards. Unless Europe acts assertively and coherently in the Arctic, there is a risk that competition will prevail over cooperation, to the detriment of the environment.

Massimo Deandreis is general manager SRM at the Economic Research Centre, Intesa Sanpaolo Bank, and president GEI of the Italian Council of Business Economists.

This commentary synthesises the key elements of the report “The Arctic route – Maritime and economic scenario, geo-strategic analyses and perspectives” published by Intesa Sanpaolo and SRM in April 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.