Now or never on European defence

It is time for Europe’s defence pioneers to move on out

The unholy trinity of Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and the Islamic State group have caused defence to return to the top of the European agenda. And the conjunction of Brexit, Emmanuel Macron, and economic recovery has opened real possibilities for progress. The idea of a ‘pioneer group’ of member states, ready to move further and faster than others in deepening their defence cooperation, has been on the table for a decade – it is now time for the Franco-German couple to make it happen.

In the jargon (indeed, in the Lisbon treaty), this is called ‘permanent structured cooperation’ – PESCO for short. The idea is that an elite group shows the way in combining their defence efforts and resources to get more bang for their euro. This is a rather different focus from NATO’s and Donald Trump’s priority, which is to increase defence spending (the famous 2 percent of GDP target). It is also actually a more relevant one. The problem with European defence is less the overall quantum of money spent than the wholly inadequate output in terms of useful defence capability that Europeans get from the money they put in.

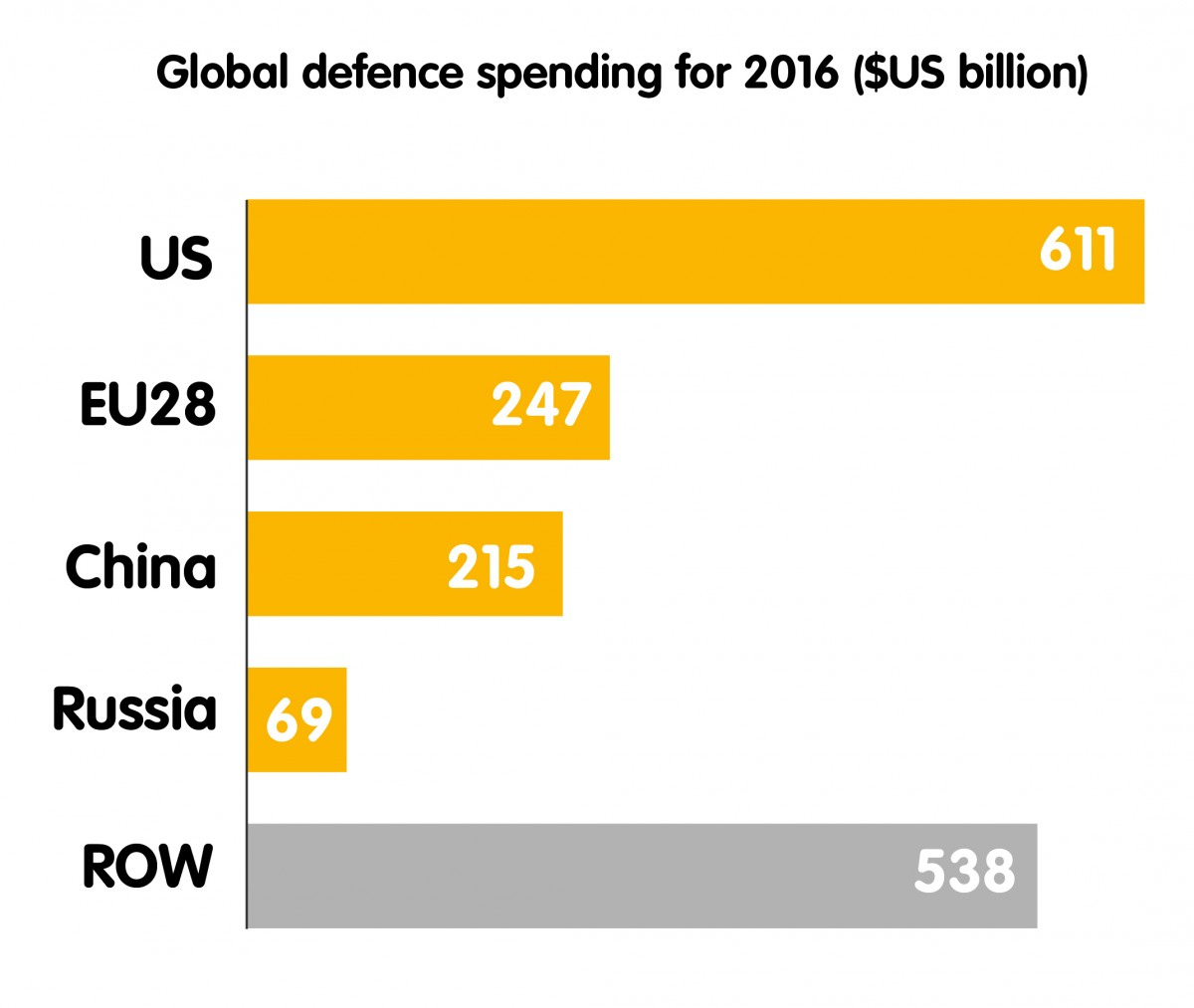

The combined defence expenditure of the EU28 is dwarfed by that of the United States. But, since even with Trump in the White House no one is yet envisaging war with the US, this comparison is irrelevant. More interesting is the fact that European defence spending still comfortably exceeds China’s – and is an astonishing three and a half times bigger than Russia’s. The fact that Europeans feel intimidated by Moscow’s military power is testament to the appalling inefficiency with which they deploy their defence resources.

Of course, the idea that Europeans should integrate their defence efforts and cooperate more closely has been around for decades, and has even achieved some modest successes, on a project-by-project basis. But the goal of PESCO is to try to move this cooperation from the retail to the wholesale level. The pioneers are to make “binding commitments to one another”. The resistance and inertia in national defence machines will remain a big problem. But greater political pressure will have been mobilised to overcome this braking effect. And, since the treaty authorises the pioneers to self-select, the relatively small number of member states who are serious about defence can aim to press ahead without the further drag of a lot of unwanted hangers-on.

Not, of course, that anyone in Brussels can put things quite that way. There is understandably a great deal of sensitivity about the ‘exclusive’ nature of the PESCO concept, and an instinct to make it as ‘inclusive’ as possible. Back in the early years of this century, when the idea first emerged, many felt that it would be worth sacrificing a bit of efficiency in order to embrace as many member states as possible, especially at a time when the European Union was doubling in size. Binding new member states into PESCO would be part of the wider process of integrating them into the EU – and, little though they might have to offer, they were all such enthusiastic pupils. (My own attempt from those days to square the inclusive/exclusive circle may still have some relevance.)

But times have moved on. Europe’s security environment has deteriorated, while a further ten years have been wasted with little to show for it beyond the further erosion of Europe’s defence technological and industrial base. The sheer mechanical difficulty of getting anything meaningfully discussed and agreed ‘at 28’ has been repeatedly demonstrated. And, naturally, some of those enthusiastic new pupils have learned to misbehave. The old assumption that members of the EU must naturally share the same values and an instinct of mutual solidarity has taken a beating. No wonder there is now so much interest in the idea of ‘multi-speed’ Europe – with defence being the obvious place to start.

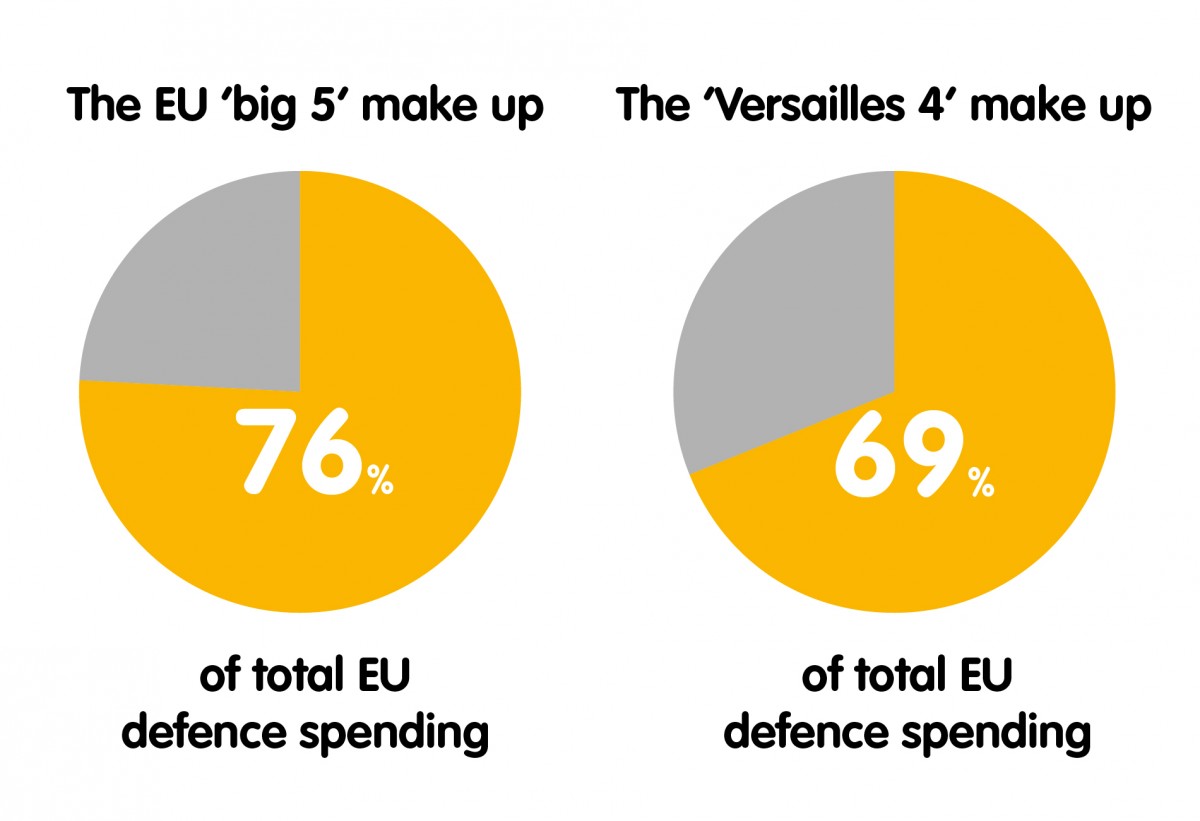

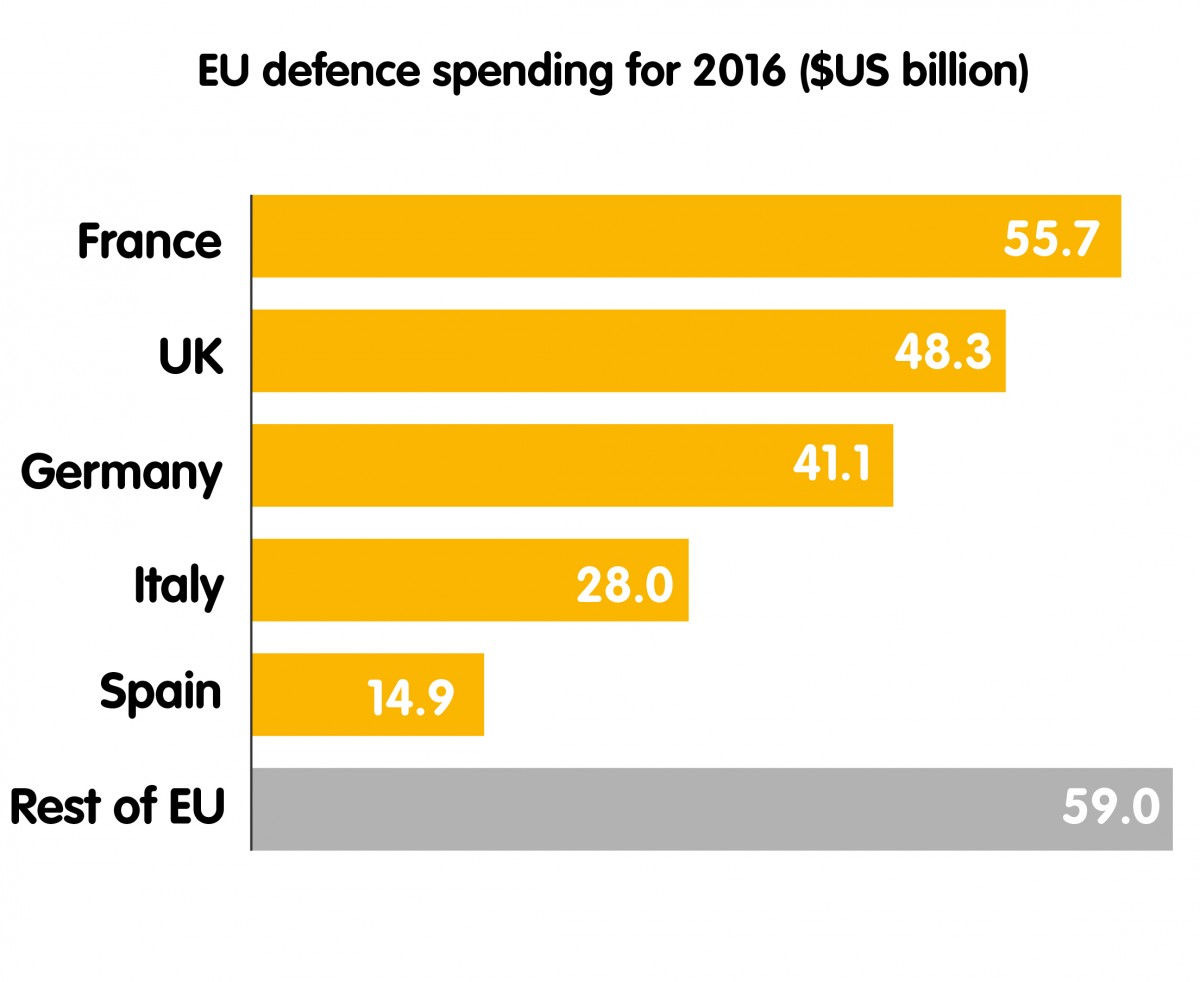

So if the emphasis today needs to be less on being nice to everyone, and more on getting something done, with whom should the Franco-German couple first syndicate whatever blueprint for PESCO they manage to agree bilaterally? Size of defence budget should not be a determinant – but it can be an indicator. Only five member states spend more than $10 billion annually on defence, and therefore account for the lion’s share of European spending. Take the United Kingdom out of the calculation and France, Germany, Italy, and Spain together provide 69 of every 100 euros spent on defence in Europe. So the first move by Paris and Berlin must be to bind in Rome and Madrid.

A few years back, Poland would have been an obvious next pick. But, since we have mentioned solidarity and shared values – surely both fundamental to defence cooperation – Warsaw, and Budapest, should be left on the bench for the time being. So the trick will be to devise a set of criteria and commitments that opens the door to valuable niche contributors such as the Swedes, or Dutch, or Finns, but keeps the initial group to a manageable eight or nine members, at most. And if that proves too tricky, then just start with four. Other member states can and should be drawn in later, once the new arrangements are up and running and the culture of actually doing things has been established. The whole point of pioneers, after all, is to blaze a trail for others to follow.

Opportunities for real progress on European defence do not come around that often. Unless the present opportunity is seized – that is, unless Paris and Berlin get PESCO off the ground in the next 12 months – we may be in for another decade’s wait. Time for those pioneers to move on out.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.