Europe’s war on terror

It is time to look closely at Europe’s evolving counter-terror activity

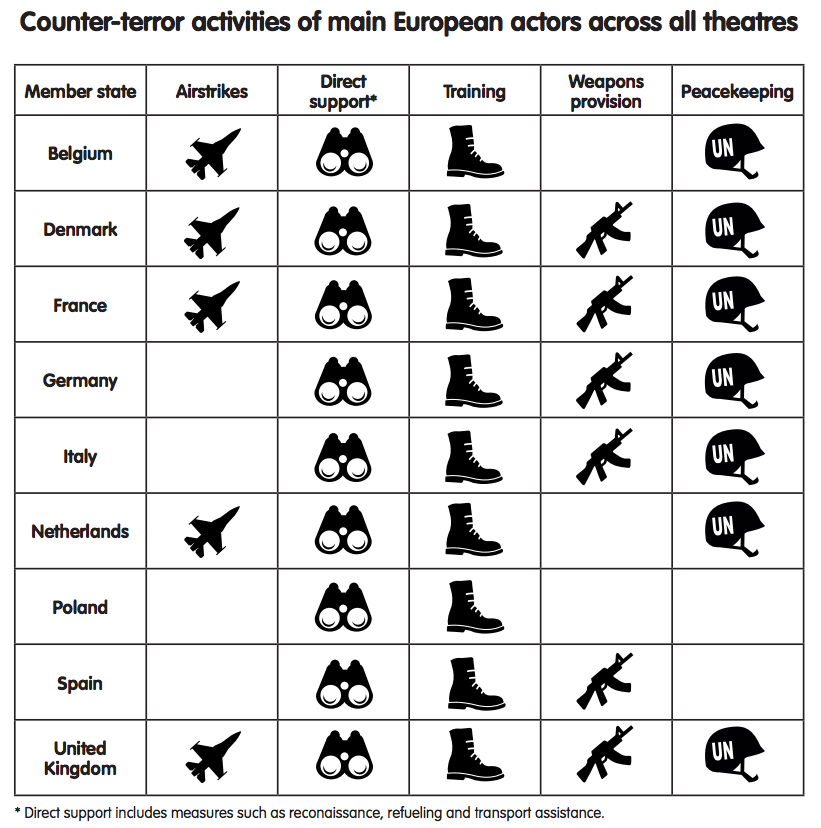

Over the last five years, European Union member states have undertaken a series of military campaigns against terrorist groups outside their borders. These actions, in the Sahel, Iraq, and Syria, represent a major new direction in European security policy. In the years after 9/11, while the United States conducted a global war against al-Qaeda, EU member states largely stayed aloof. But changes in the nature of the terrorist groups in the regions surrounding Europe have prompted a change in the European response, leading to a new wave of European counter-terror wars.

The biggest change that terrorist groups have undergone is a shift towards controlling territory. Al-Qaeda, under Osama bin Laden, was hesitant about any move to set up governing regimes. But in the wake of the turmoil that has spread across the Middle East and northern Africa since 2011, the Islamic State group and various al-Qaeda affiliates have seized control of large parts of several countries. It was the spectre of these ‘safe havens’ not far from European shores that drew EU member states into military action to roll back the territory under the sway of terrorist groups. France’s intervention in Mali in 2012 was the first of these operations, and the wide European involvement in attacks on ISIS in Iraq and Syria represents their fullest development.

Europe’s move into counter-terror war was improvised rather than strategically planned. In both Mali and Iraq, military action was launched quickly to halt the momentum of advancing armed groups. The result is that there has been little systematic thought about the implications of these military actions. It is now a good moment to take stock of what they have achieved and of the unresolved questions that surround them, since European countries seem unlikely to stop mounting such campaigns any time soon.

Militarily, the campaigns by EU member states and their coalition allies have achieved some notable results. Extremist groups no longer hold territory in northern Mali, and the area controlled by ISIS in Iraq and Syria has shrunk dramatically. Operations to recapture ISIS’s last major urban strongholds in Mosul and Raqqa are under way. These successes derive from the fact that air attacks against the groups involved have been combined with ground operations, normally conducted by partner countries.

But these successes at the same time testify to the limits of what military action against terrorist groups can achieve. In Mali, jihadist groups have been dispersed across the Sahelian desert, but they remain capable of launching deadly attacks; terrorist incidents have actually increased in the region as the groups shift away from conventional military operations. In Libya, where the US took the lead and European countries were less involved, ISIS was driven out of Sirte but is regrouping in the country’s south. These groups are opportunistic and adaptive, able to shift easily between terrorism and insurgency. As fighters become more mobile and spread across ungoverned spaces, Western countries have increasingly resorted to targeted strikes that have a ‘whack-a-mole’ quality: they can kill individual fighters, but not erase terrorists’ base of support.

The danger here is that Europe may prioritise military action – which is comparatively straightforward and shows the public that something is being done – over the harder and longer-term effort to resolve underlying conflicts or governance failures that allow terrorist groups to implant themselves. Admittedly, solving the problem of regional exclusion in Mali – or, after the capture of Mosul, sectarian divisions in Iraq – is a much greater challenge than dropping bombs on terrorist fighters, and likely to unfold over the course of several years. But without a serious effort to achieve these goals, military action could become an open-ended process of merely trying to keep a lid on the problem.

Directed against groups that combine terrorism with more conventional military operations, Europe’s counter-terror wars have also been hybrid in nature. Along with operations to recapture territory or support local ground forces, they have in some cases involved targeted strikes against individual enemy fighters. France and the United Kingdom have conducted such attacks directly and also provided information to the US to use in drone strikes. Among the targets have been figures such the British ISIS members Reyaad Khan and Mohamed Emwazi (also known as “Jihadi John”) and the French recruiter and attack planner Rachid Qassim, killed by the US in Iraq in February 2017. It was recently reported in the American press that France has provided Iraqi soldiers with a hit list of French nationals fighting for ISIS to hunt down and kill as they recapture ISIS-held territory.

These operations highlight an additional complexity of European military action against ISIS: it takes place in a context where the boundary between the external and internal dimensions of counter-terrorism has been blurred. Fighters train in Iraq and Syria to conduct attacks on European soil, or manipulate local recruits through a process of ‘remote control’ plotting. Yet European countries operate on the basis of a supposedly clear division between military action overseas and law enforcement at home. This leads to anomalies – such as France sending an aircraft carrier to the Middle East after the Nice truck attack, conducted by a French resident on French soil. And it leads to legal and moral grey areas – as with the above-mentioned suggestion that France is encouraging the killing of ISIS fighters in Iraq before they can return to French territory.

The effort against terrorist groups overseas and radicalisation at home is one where the EU and its member states are still elaborating their responses. It is one of the most serious security challenges that Europe faces. As regards the external dimension, the balance between military action and a more comprehensive political approach needs careful assessment. And there is still work to be done in defining the legal and moral framework for military operations against amorphous non-state groups that operate transnationally and move seamlessly between insurgent activity on the ground and orchestrating terrorist attacks at long distance.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.