A European approach to military drones and artificial intelligence

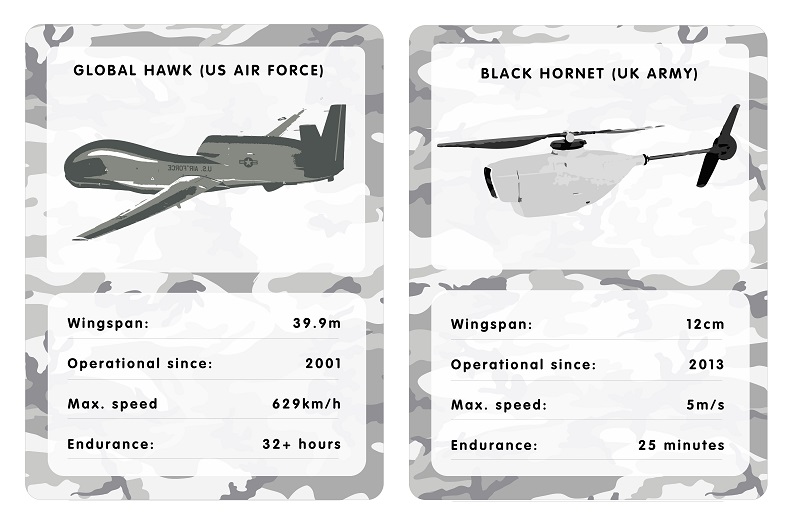

When people hear the word ‘drones’, they think of targeted killings and the United States. They picture the “Predator” or the “Reaper”, the world’s most notorious drones, armed with the equally notorious “Hellfire” missiles. They do not generally think of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems (ISR), of small ‘toss-in-the-air’ drones, or of Europe.

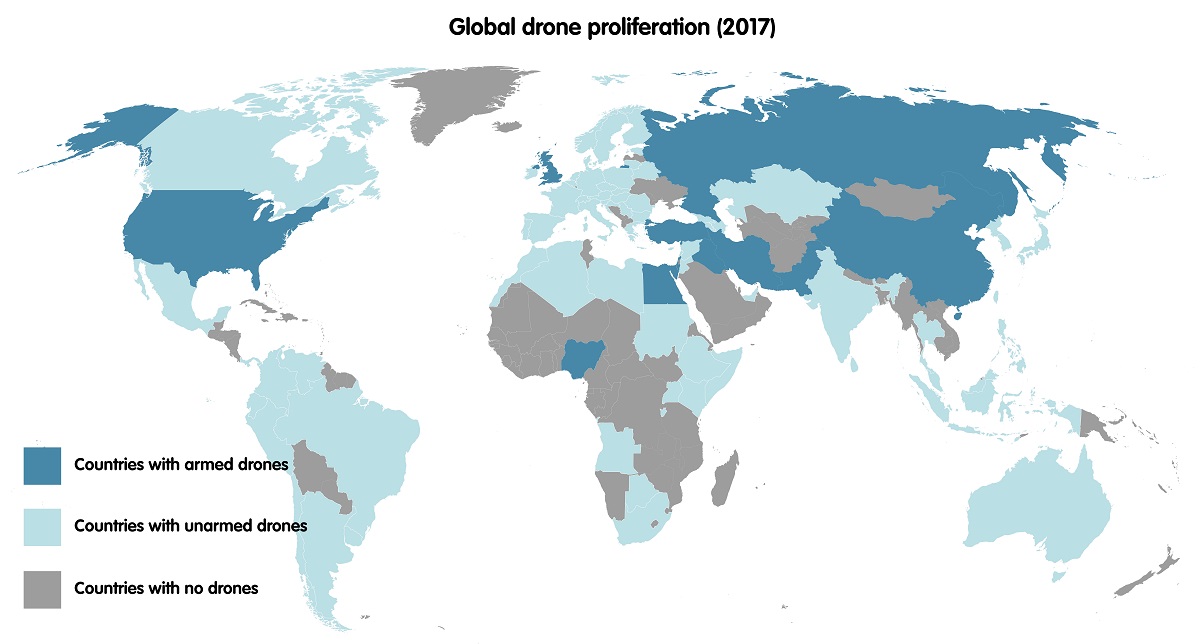

This view is as widespread as it is wrong. As of 2017, 90 countries around the world have military drones in their arsenals and 11 states have armed drones. The overwhelming majority of drones are small, unarmed, and used for ISR. All European states but three have military drones, mainly unarmed ones.

Modern drones have been deployed on battlefields for over a decade.[1] But there is no reason to believe that we have found the best way to use them yet. The use by the US of armed drones for targeted killing in places such as Pakistan, Yemen, or Somalia represents only one way of using drones – but it is the one that has received all of the attention. The European drone debate, from its beginning, has been unduly influenced by the US experience. And, despite this attention, the European Union has not succeeded in devising a common stance on US drone use.[2]

Europe’s reductive approach to drones has caused it to unnecessarily constrain its thinking in two ways:

First, it has led policymakers to overlook the role of unarmed drones. Armed drones certainly have their place in military operations, but my research shows that, from an operational perspective, unarmed drones – which provide levels of ISR never seen before and at the lowest levels of the military hierarchy – may be at least as revolutionary as armed drones, since they can make a substantial difference in military operations and save lives.

Second, more generally, it is a terrible idea to focus on only one specific usage of a new technology. Generations of scholars have dedicated their careers to finding out what makes military technology ‘revolutionary’. While many different explanations have been brought forward, there is universal agreement on one point: it is not (just) about the technology, it is about how you use it. What makes a technology truly ground-breaking, effective, and possibly revolutionary, is policy and doctrine.

The classic example for this is tank warfare. Tanks had been on the battlefield since 1916, but it was the Wehrmacht’s introduction of independent armoured divisions and their innovative use of radio in the second world war that allowed them to rapidly break through enemy lines. This was what made tanks revolutionary.

European countries should end their fascination with American drone warfare and consider how drones can best suit the needs of their own armed forces. This will help to focus the debate on how best to use the technology, and what capabilities to invest in.

There is a window of opportunity now that Europe should take advantage of. European armed forces have largely returned from missions during which they had their first real experience of using drones, such as in Afghanistan and Iraq, or are currently using them in ongoing operations in the Sahel/Mali and Syria.[3] Most countries bought drones as an urgent operational requirement, but European armies are still thinking about where they fit in. From a military doctrine point of view, this means that now is an appropriate time to step back, evaluate, and invest.

While armed forces in each European country must assess individually what type of drone use fits them best, the EU should use the new EU defence fund for investment in a common, small, and robust European drone.

Drones are already high on the list of European priorities: France, Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland are working on the “nEUROn” drone; Germany and Spain on “Barracuda”; the UK is developing the technology demonstrator “Taranis”; France and the UK in 2016 agreed to invest £1.5 billion in a new combat drone; France, Italy, and Germany began a drone partnership in 2015, and NATO is acquiring five US Global Hawk drones.[4]

But while European investment in future technology is to be welcomed, these projects all face common problems:

a) despite some of them having begun many years ago, there is little to show for the investment;

b) as expensive, high-tech combat systems, it is unlikely that they will be needed by many European forces;

c) because they are high-tech and armed, they are not easily exportable.[5]

It would be of much more immediate use to invest in a common European small, robust, ISR drone system (maybe optionally armed) and related swarm technology that enables them to work collectively. Small ISR drones have more than proven their worth and are being used around the world. Indeed, their continuous demand in Europe and abroad is guaranteed because of their value in ISR activities. At this point, the market is dominated by the US “Raven” (and indigenous systems). But the Raven is not without its problems. Raven drones were recently hacked by Russian forces within hours of being sent above the battlefield in eastern Ukraine. Ukrainian forces had to resort to crowdfunded drones instead.[6]

There is a clear opening for a more robust small European drone system. It would be of enormous operational advantage if European forces had common systems, ensuring interoperability, common training, and much more.

Focusing on smaller drones that can work together as a swarm would also put Europe in a strong position regarding the next potential revolutionary military technology – artificial intelligence (AI). AI is not solely (or even primarily) a military technology, which is why Europe’s approach to AI cannot be exclusively military. But AI will be part of the future of warfare, initially through autonomous weapons that can find and engage targets independently and operate in swarms. Drones and other unmanned systems will be the first to be affected – indeed they already are being affected.[7]

It is crucial that Europe does not repeat the mistakes it made with drones when it comes to AI. Chasing developments in the US instead of thinking strategically about a European position and use for the technology would be a grave error. Europe has an opportunity to ensure that the next, AI-powered drone system on everyone’s lips is European-made.

[1] The Soviet Union had drones, the US used them in the Vietnam War, and Israel in the Yom Kippur War and in 1982 in Lebanon. But drones really came of age around the year 2000, when the technology reached maturity and positive experiences in Kosovo pushed European countries and the US to invest more. 9/11 and the wars on terror dramatically increased demand for and investment in the military technology.

[2] Anthony Dworkin “Drones and targeted killing: defining a European position”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 3 July 2013, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/drones_and_targeted_killing_defining_a_european_position211.

[3] Denmark, Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, and the UK used drones in Afghanistan; the UK and Italy used drones in Iraq; France, Germany, and Sweden have, or are, using drones in the Sahel region; and the UK is using drones in Syria.

[4] On European drone project see Ulrike Franke “U.S. Drones Are from Mars, Euro Drones Are from Venus, War on the Rocks, 19 May 2014, https://warontherocks.com/2014/05/u-s-drones-are-from-mars-euro-drones-are-from-venus/.

[5] Europeans may be reticent to export high-tech weaponry and the exports of such systems is restricted by existing export control treaties.

[6] Bjoern Mueller, “Krieg fuehren per Crowdfunding”, FAZ, 11 March 2017.

[7] Ulrike Franke, „Automatisierte und autonome Systeme in der Militär- und Waffentechnik“, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte APuZ, August 2016.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.