The Western Balkans’ statistical black hole

How many people live in the Western Balkans? The unreliability of statistics on the region often makes it hard to tell.

How many people live in the Western Balkans? The unreliability of statistics on the region often makes it hard to tell. As a recent article in the Guardian drawing on ECFR research discusses, many Europeans are more concerned about emigration than immigration. The article includes a graphic purportedly showing that Kosovo lost 15.4 percent of its population between 2007 and 2018. This is the result of both guesswork and a complete misunderstanding of published data. According to our calculations, Kosovo’s population declined by around 4.27 percent between 1990 and 2017.

Such misunderstandings are common: quite apart from the lack of reliable data, demographic statistics on the former Yugoslavia are often misused – inflated or minimised – for political ends. In 2006 research by the European Stability Initiative demonstrated how statistics in Kosovo had long been distorted by the region’s governments and, worse, international organisations – which had their own interests in using incorrect data. Once these international bodies got in on the game, they gave a veneer of legitimacy to fake facts.

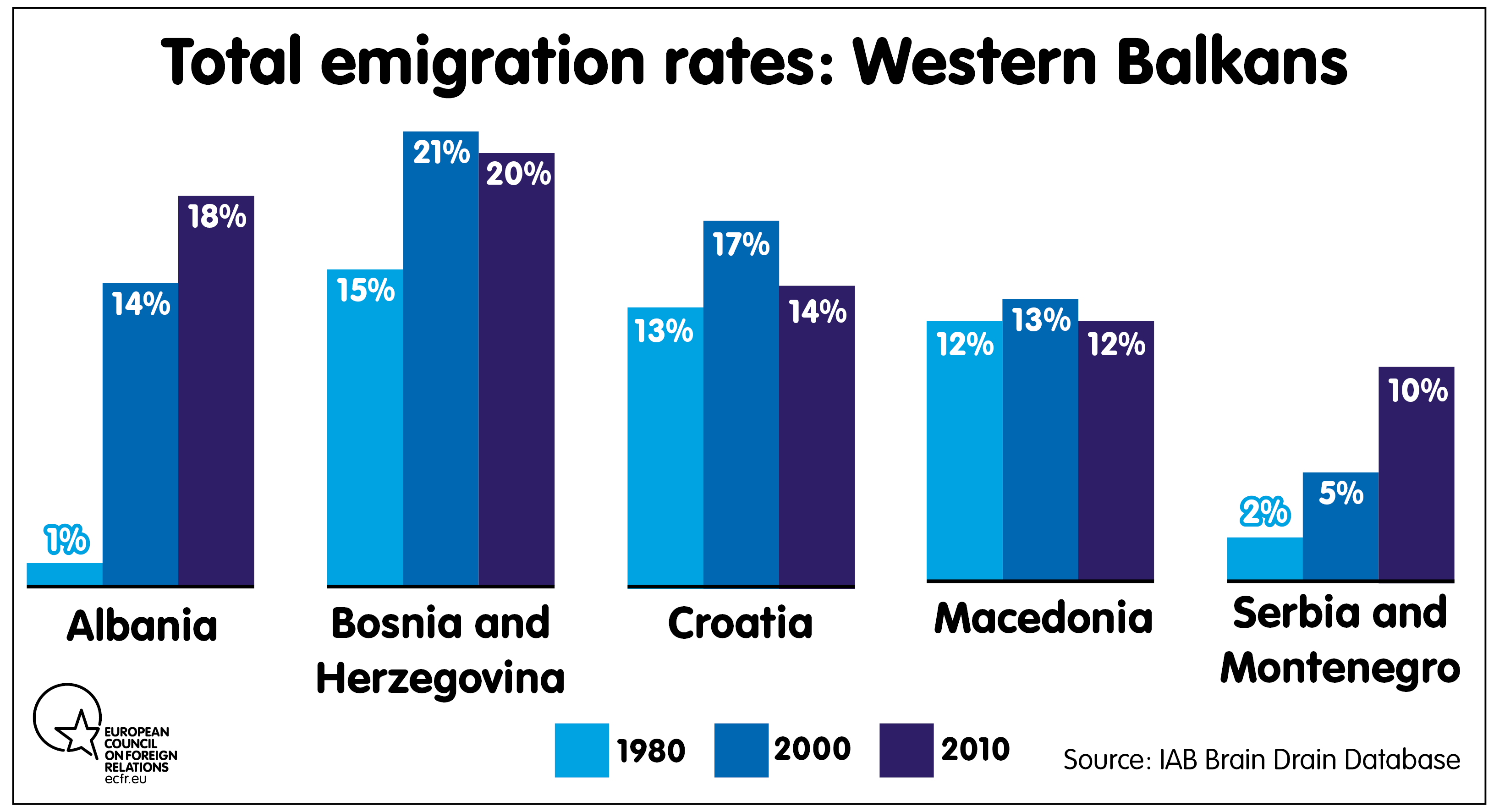

The Guardian’s Kosovo figure might be just the most recent example of the use of incorrect data, but it highlights the desperate need to improve the collection of statistics in and about the Western Balkans. Low birth rates and high levels of emigration have long since succeeded the era of dislocation and death caused by the wars of the 1990s. Although the region has produced skilled demographers and statisticians, they often emigrate, are starved of funds, are under pressure to produce politically useful data, or are too few in number.

In these circumstances, the complexity of demographic issues leaves policymakers without access to credible data. The resulting problems are compounded by the legacy of the 1990s conflicts: large numbers of people are registered as living in or being citizens of more than one former Yugoslav state and, sometimes, reside somewhere else entirely.

With the intensification of the emigration crisis in the last few years, local political elites have remained reluctant to seriously tackle these challenges. As emigration is largely a reaction to political failure, including pervasive corruption, in the Western Balkans, politicians there frequently seek to gain advantage from the crisis rather than attempt to use what limited resources they have to deal with deep-seated issues. The short-term logic of this is simple. If people emigrate, unemployment figures decline and remittances increase. The government needs to pay fewer teachers and, while doctors also emigrate, so do many of their patients. Thus, policy challenges seem less grave than they otherwise might have. But the key questions remain: how many people have left, and how many remain?

A history of fuzzy statistics

The roots of the problem go back decades. Yugoslavia’s system for collecting statistics was generally credible but suffered from structural problems in relation to population data – at least, for the non-specialist. The effects of this are still apparent today. Policy analysts and journalists often use the last Yugoslav census, taken in 1991, as a starting point for their work on the Western Balkans. For example, most analysis of the region states that the population of Bosnia-Herzegovina was 4.4m before the war, using this figure for discussions of wartime losses and calculations of post-conflict population decline. However, examine the data in more detail and you will find that this figure includes 234,213 gastarbeiter (guest workers) and their families who were not in the country. And this is only going by the official figure. Some demographers put the number of people who actually lived in Bosnia-Herzegovina at the outbreak of the war at as low as 4m.

The explanation for this anomaly is straightforward. After large numbers of Yugoslav citizens began working abroad in the 1960s, officials reluctant to report a population decline began including people who lived and worked abroad in the census. In 1991 this official figure gave the false impression that around 1m more people were resident in Yugoslavia than was the case. For this reason, calculations of population decline in the former Yugoslavia between 1991 and 2015 vary between 2.46m and 3.98m, depending on who you include.

In Kosovo, the problem is even more complicated. In 1991 Albanians boycotted the census, so the authorities estimated their numbers. And, every year after that (including those of the war and the Serbian exodus), official estimates used those of previous years and ignored the fact that the fertility rate had dropped dramatically from its high pre-conflict level. Today, it does not help that when a census was finally held in 2011, Serbs in the north of the country boycotted the exercise (although they made up a far smaller proportion of the population than Albanians did in 1991).

Incorrect numbers can have direct political consequences

North Macedonia held its last census in 2002 and has indefinitely postponed its 2011 census due to ethnic politics. Bosnia held its last census in 2013, but its results were marred by controversy relating to ethnic groups’ appeals to kith and kin abroad to come home for the exercise. In Serbia, Albanians from south of the country boycotted the 2011 census.

The challenge for policymakers

The key problem is that a lack of reliable statistics makes serious policymaking almost impossible. The authorities need to know whether their country has lost, for instance, 1 percent or 11 percent of the population – and whether population changes are occurring everywhere or only in certain regions – if they are to devise an effective response.

One issue is that access to accurate data is not a priority anywhere in the region. On top of this, the responsibility for collecting population data typically falls to several bodies, including ministries of interior, labour and social welfare, and the diaspora. Above all, governments try – if they have the opportunity and political will to do so – to keep track of who is in the country rather than who has left.

In many cases, there are compelling political reasons not to worry too much about who has left. For example, long-outdated electoral rolls can provide an opportunity for stealing an election. Electoral manipulation aside, incorrect numbers can have direct political consequences. During North Macedonia’s September 2018 referendum on whether to change the name of their country, 94 percent of voters supported the proposal – but only 36.8 percent of those on electoral rolls participated. In this way, the referendum seemed to fall below the required voter turnout threshold. Yet a big reason for the low turnout was that the electoral roll was so out of date that it included the names of hundreds of thousands of people who were abroad but remained registered as residents.

Moreover, it can be as hard to gather data about emigration abroad as it is at home. The Croatian National Bank has done pioneering work in this area but, even so, such efforts are prone to error. Take the case of a woman from Osijek, in eastern Croatia. In any one year, she may spend six months at home but work in two other countries for the remainder. As a result, the data will suggest that she is resident in all three countries. The number of Croats living abroad is also complicated by the fact that some of them – maybe as many as 20 percent – are actually from Bosnia but own EU passports by virtue of being, or claiming to be, Bosnian Croats who have a right to Croatian citizenship.

Statistical agencies in much of the former Yugoslavia lack the financial resources and political environment to gather accurate statistics. Sometimes, ethnic tension distorts results or – as in the case of North Macedonia – even attempts to gather data in the first place. Meanwhile, Western Balkan statisticians have little opportunity to jointly analyse challenges in data collection and interpretation. Due to the Yugoslav legacy, people’s overlapping official identities can completely muddy the statistical waters – especially in relation to where they say they live.

Can the EU help?

Because the European Union classes the countries of the Western Balkans as “enlargement countries” (potential future members), Eurostat has attempted to address the weaknesses in statistics on the region. The European Commission’s 2016 report on Serbia noted that the country was only “moderately prepared” to gather population statistics, arguing that it needs to strengthen the capacity of its statistical office, “notably by increasing its staff and their qualifications”. Its report on Bosnia for that year discussed the weakness built into the system by the country’s use of three statistical agencies that mostly do not cooperate with one another in key areas. This lack of cooperation between agencies is apparent across the region. It would be a huge step forward for them to adopt shared methodologies and harmonised working practices on migration and overlapping citizenships.

Similarly, Western Balkans statistical offices gather only a fraction of the data their EU counterparts do. And, even with the data they do collect, they often lack the capacity to analyse and interpret it. Hence, the national and regional socio-economic assessments policymakers rely on often suffer from a major shortage of statistical input.

People’s overlapping official identities can completely muddy the statistical waters – especially in relation to where they say they live

The EU can help make far more effective use of Eurostat to gather data and coordinate its use, harmonising methodologies and working practices between the countries migrants travel between. Eurostat should be able to suggest ways to assess flows and stocks of migrants that respond to current migration patterns, not least by improving the transparency of its work.

The EU has already invested billions of euros in infrastructure in the Western Balkans. But accurate statistics, though invisible to most citizens, are as important as the refurbished schools and new motorways slowly appearing across the region. There is a need for European investment to tackle the dearth of up-to-date information in the region. This would likely cost less than a few kilometres of motorway, but the results would provide the authorities with data they can build effective policy on for decades to come.

Access to accurate data about the make-up of society is especially important in a largely post-industrial, urbanised Europe reliant on globalisation, pan-European integration, and advanced technology. Only governments that have this capacity will be able to both modernise and, in the Western Balkans, begin to stem the outflow of people who are educated, of working age, and likely to start families (at a time of frighteningly low fertility rates).

It is often said that data is the oil of the future. Given that this is as true for the Western Balkans as any other region, it is vital that countries there and in the EU do everything they can to train and equip the agencies that harvest the numbers necessary for building modern states. In the past, European countries modernised by replacing scythes with combine harvesters; it is now time for them to modernise the ways they harvest data.

Tim Judah is the Balkans Correspondent of the Economist and a fellow at the Europe’s Future project of the Institute for Human Sciences.

Alida Vračić is a visiting fellow with ECFR’s Wider Europe Programme and co-founder and executive director of Populari, a think-tank specialising in European integration in the Western Balkans, politics, governance, civil society, and post-conflict democratisation.

The original title photo sourced from NoiZZ.rs.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.