The remarkable rise of continental Euroscepticism

A new ECFR analysis shows that trust in the EU has plummeted across the continent. Both southern debtors and northern creditors feel like they are victims.

Trust in the EU has plummeted across the continent. Both southern debtors and northern creditors feel like they are victims.

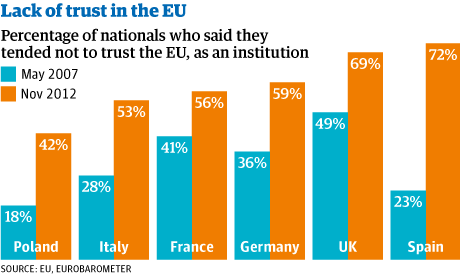

Once it was seen as a British disease. But Euroscepticism has now spread across the continent like a virus. As the data from Eurobarometer shows, trust in the European project has fallen even faster than growth rates. Since the beginning of the crisis, trust in the EU has fallen from +10 to -22 in France, from +20 to -29 points in Germany, from +30 to -22 points in Italy, from +42 to -52 points in Spain, from +50 to +6 points in Poland and from -13 to -49 points in the UK.

What is striking is that everyone in the EU has lost faith in the project: both creditors and debtors, and eurozone countries, would-be members and “opt-outs”. Back in 2007, people thought that the UK, which scored minus 13 points in trust, was the Eurosceptic outlier. Now, remarkably, the four largest eurozone countries have even lower levels of trust in the EU institutions than Britain back in 2007. So what is going on?

The old explanation for Euroscepticism was the alleged existence of a democratic deficit within the EU. Decisions, critics said, were taken by unaccountable institutions rather than elected national governments. But the current crisis is born not of a clash between Brussels and the member states but a clash between the democratic wills of citizens in northern and southern Europe, the so-called centre and periphery. And both sides are now using the EU institutions to advance their interests.

In the past, there was an unwritten rule that EU institutions would police the single market and other technical areas of policy – from common standards for the composition of tomato paste to lawnmower sound emissions – while national governments would continue to have a monopoly on the delivery of services and policymaking in the most sensitive areas on which national elections depended.

Since the crisis began, citizens in creditor countries have become resistant to taking responsibility for the debts of others without having mechanisms for controlling their spending. With the fiscal compact and demands by the ECB for comprehensive domestic reforms, Eurocrats have crossed many of the red lines of national sovereignty, extending their reach way beyond food safety standards to exert control over pensions, taxes, salaries, labour market, and public jobs. These areas go to the heart of the welfare states and national identities.

To an increasing number of citizens in southern European countries, the EU looks like the IMF did in Latin America: a golden straitjacket that is strangling the space for national politics and emptying their national democracies of content. In this new scenario, governments come or go but policies remain basically the same and cannot be challenged. Meanwhile, in northern European countries, the EU is increasingly seen to have failed as a controller for the policies of the southern rim. The creditors have a sense of victimhood that mirrors that of the debtors.

If sovereignty is understood as the capacity of the people to decide what they want for their country, few in either the north or the south today feel that they are sovereign. A substantial part of democracy has vanished at the national level but it has not been recreated at the European level.

In a fully-functioning national political system, political parties would be able to voice these different perspectives – and hopefully act as a referee and find common ground between them. But that is precisely what the European political system cannot deliver: because it lacks true political parties, a proper government and a public sphere, the EU cannot compensate the failures of national democracies. Instead of a battle of ideas, the EU has been marred by a vicious circle between anti-EU populism and technocratic agreements between member states that are afraid of their citizens.

Is the rise of anti-EU populism here to stay? The hope is that as growth picks up, Euroscepticism will weaken and eventually recede. But the collapse of trust in the EU runs deeper than that. Enthusiasm for the EU will not return unless the EU profoundly changes the way it deals with its member states and its citizens.

Germany – Ulrike Guérot

Germans see themselves as the victims of the euro crisis. They feel they have been betrayed and fear that they will be asked to pay higher taxes or accept higher levels of inflation in order to save the euro. But the jury is still out in Germany on the EU itself. The Eurobarometer data shows that 56% of Germans have “no trust” in the EU while only 30% have a “fairly positive” image of the EU.

At the same time, however, populism has so far been contained: the mainstream political parties all support the euro and recent polls show that three-quarters of Germans are against leaving the euro. A new anti-euro party, the Alternative for Germany, has just been set up but is so far projected to get at best 2% of the vote in September's general election. Germans may not love the euro anymore but that does not mean they want to leave it. As recent polls show, 3/4 of Germans reject leaving the euro.

France – Thomas Klau

For once, France is no exception: since the crisis began trust in the EU has diminished and its image has worsened. In 2012 the number of French respondents who “tend not to trust” the EU rose to 56 % from 41% in 2007.

This negative judgement about the EU's response to the crisis has already had an impact on French politics: it is undoubtedly a factor in the even deeper entrenchment of the violently anti-EU, far-right National Front in France's political life and an equally significant factor in the political and media success of the radical left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

However, if the French people are able to identify a visible, resolute and accountable leadership at EU or eurozone level that gives economic recovery priority by focusing on debt reduction as much as on investment strategies, growth policies and indeed takes the first step towards pan-European welfare models, then the anti-EU trend could be reversed.

UK – Hans Kundnani

Perceptions of the EU in the UK have changed less dramatically than in many other member states: even in 2004 there was a relatively low level of trust in, and a relatively negative image of, the EU.

The percentage of those who “tend not to trust” the EU has gone from 48% in 2004 to nearly 80% in 2012. But this increase began long before the crisis began and is unlikely to be reversed even if and when the crisis is resolved.

Given that the UK is unlikely to join the single currency in the foreseeable future, it will be in the third tier of the emerging three-tier Europe (the first made of eurozone members, the second of would-be ins and the third made of eurozone “outs”, ie those who would not join the eurozone even if they could). Thus the question from a British perspective is how the UK can retain influence from the margins of Europe. In particular, there is likely to be a demand for a new settlement that guarantees the rights of eurozone “outs”.

Italy – Silvia Francescon

Austerity is changing perceptions of the EU among Italian citizens – especially among the young, 40% of whom are unemployed. The recent Italian election vote showed that Italians have lost their faith in and patience with Brussels and Berlin and no longer believe that the end of the crisis is around the corner.

But although trust in the EU has decreased in Italy, a majority of Italian respondents still see themselves as European citizens and identify with Europe. In a recent poll, only 1% wanted to leave the EU. Instead, a large majority – especially among the business community – want to move ahead to a real political union that is more democratic and more social than the current EU. The election did not show that Italians want less Europe. Rather, they want a different Europe: one that is more flexible and more symmetrical, less focused on austerity and more focused on investment in the real economy.

Spain – Jose Ignacio Torreblanca

For decades, Spain saw its relationship with Europe through the eyes of Ortega y Gasset's prescription: “Spain is the problem and Europe is the solution”. The dramatic and unprecedented decline in trust in the EU since the crisis began is not simply a result of austerity. After all, Spain went through painful reforms in order to join the EU and, later, the euro, and overcome their difficult past.

Now, however, the lack of a clear vision about either the national or European future means there is no consensus and legitimacy for the sacrifices that are being demanded of them. Spaniards do not blame Europe for the crisis and do not want to leave the euro. What has eroded their loyalty to, and trust in, Europe is that they have no voice and cannot challenge policies that are clearly not working. Spaniards have not become Eurosceptics – but they have turned into fierce Eurocritics.

Poland – Piotr Buras

For the first time, the percentage of Poles who “tend not to trust” the EU (46%) is higher than the percentage of Poles who do “tend to trust” it (41%) – a remarkable development for a country that has traditionally been pro-European. To be sure, the EU still has higher approval ratings than the national government, parliament or public television.

However, the EU seems to have lost its reputation as the anchor of stability for a country undergoing a huge social and economic transformation. In particular, the Poles are sceptical about the future of the common currency and only 29% of them wish now to join it. These public attitudes pose a dilemma for the country's political elite whose ambition is to be at the centre of power in Europe. Poland's objective in the years ahead will be to stay as close to the core as possible while defending the integrity of the whole EU project.

Bulgaria – Dimitar Bechev

Bulgaria is a rare case where trust in the EU has marginally increased since the country joined in 2007. According to Eurobarometer 54% trusted the Union in 2007, and by autumn 2012 the figure was 60%. Distrust has risen marginally too: from 21 to 24%.

Bulgaria is following an old familiar pattern: citizens trust Brussels because of the unpopularity of domestic institutions(the most recent Eurobarometer polling suggested that 74% distrust the national parliament and 79% hold a negative view of political parties). The EU therefore continues to serve as an external corrective for dysfunctional politics at home.

The wave of mass protests in February and March that triggered snap parliamentary elections speaks to the fragility of this state of affairs. Although popular anger was directed at Bulgarian elites who were blamed for poverty and rampant corruption, the EU was not invoked as the cure. Private investors from other member states came also under fire, suggesting a shift to economic nationalism that might also provide a fertile ground for Euroscepticism in the future.

A version of this article was published in English by the Guardian, in French by Le Monde and in Spanish by El Pais.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.