Table scrap: Budget talks in a fragmented Europe

It will be difficult for the member states that are most invested in the EU’s global role to prevent a reduction in the external portion of its budget.

The European Council has begun its first meeting under its new leadership. Former Belgian prime minister Charles Michel is presiding over the discussions as president of the Council. And there is another new face in the proceedings now that Sanna Marin, who became the world’s youngest prime minister this week, has taken up the six-month Finnish presidency of the body. In some ways, it would have been convenient for the Council’s agenda to have focused on issues that its members could rally around at the end of a turbulent and transitional 2019. But – rather than a cosy, forward-looking discussion to celebrate the end of EU institutions’ period of change – they will face plenty of tests and traps.

The big-ticket item on the Council agenda is climate change. And those campaigning outside the Justus Lipsius building today will not let leaders forget this. But, while all EU leaders agree that a Green New Deal needs to be prominent on EU institutions’ agenda, there are big divisions on the exact policy measures it should comprise – and on whether the proposals European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen just launched are ambitious enough. The May 2019 European Parliament election saw the Greens increase their tally of MEPs from 52 to more than 70. But it was almost exclusively a western European phenomenon. As many of the member states most wary of the financial costs of commitments to tackle climate change are central and eastern European, it is unlikely that this discussion will go smoothly. This is particularly true after a tense week in which the members of the Visegrád group – the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia – felt that they came under attack in the closed Article 7 talks in the General Affairs Council.

But with Prime Minister Boris Johnson having won the large parliamentary majority he needs to take the United Kingdom out of the European Union in January 2020, Brexit will also occupy some of EU leaders’ attention. They know that, when the UK finally leaves the Council table, the real negotiations on the future relationship between the sides – including a trade deal – will begin. As Johnson is pushing for a quick agreement, to allow for a short transition period in 2020, there will be intense pressure for member states to maintain a unified position, despite the real differences between them on how close the UK-EU relationship should be.

Perhaps the biggest row of all will concern the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). The Finnish presidency has presented a compromise proposal (referred to as the “negotiating box”) for a budget of 1.07 percent of the EU27’s GNI. Significantly smaller than the Commission initially proposed, the budget has already caused controversy in the European Parliament and among supporters of increased cohesion funds in southern, central, and eastern states – who see it as a betrayal of the principle of redistribution in the EU, and insufficient to fulfil the European Commission’s agenda for a more ambitious union. But those on the other side of the argument are unhappy too. Germany and the New Hanseatic League – comprising Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Sweden – view the budget as too large, as they do not want it to exceed 1 percent of GNI. (The Finnish presidency believes that, given these differences between member states on the issue, the best it could hope for was to distribute discontent between them evenly.)

The longer the MFF discussions continue, the longer the delay to the Commission’s implementation of its work programme.

As shown by surveys the European Council on Foreign Relations carried out in the first half of 2019 – which involved more than 60,000 respondents spread across 15 EU member states – there are no easy solutions to this problem. Where and how the EU spends its money goes to the heart of what sort of union citizens want to live in. And they fundamentally disagree on this.

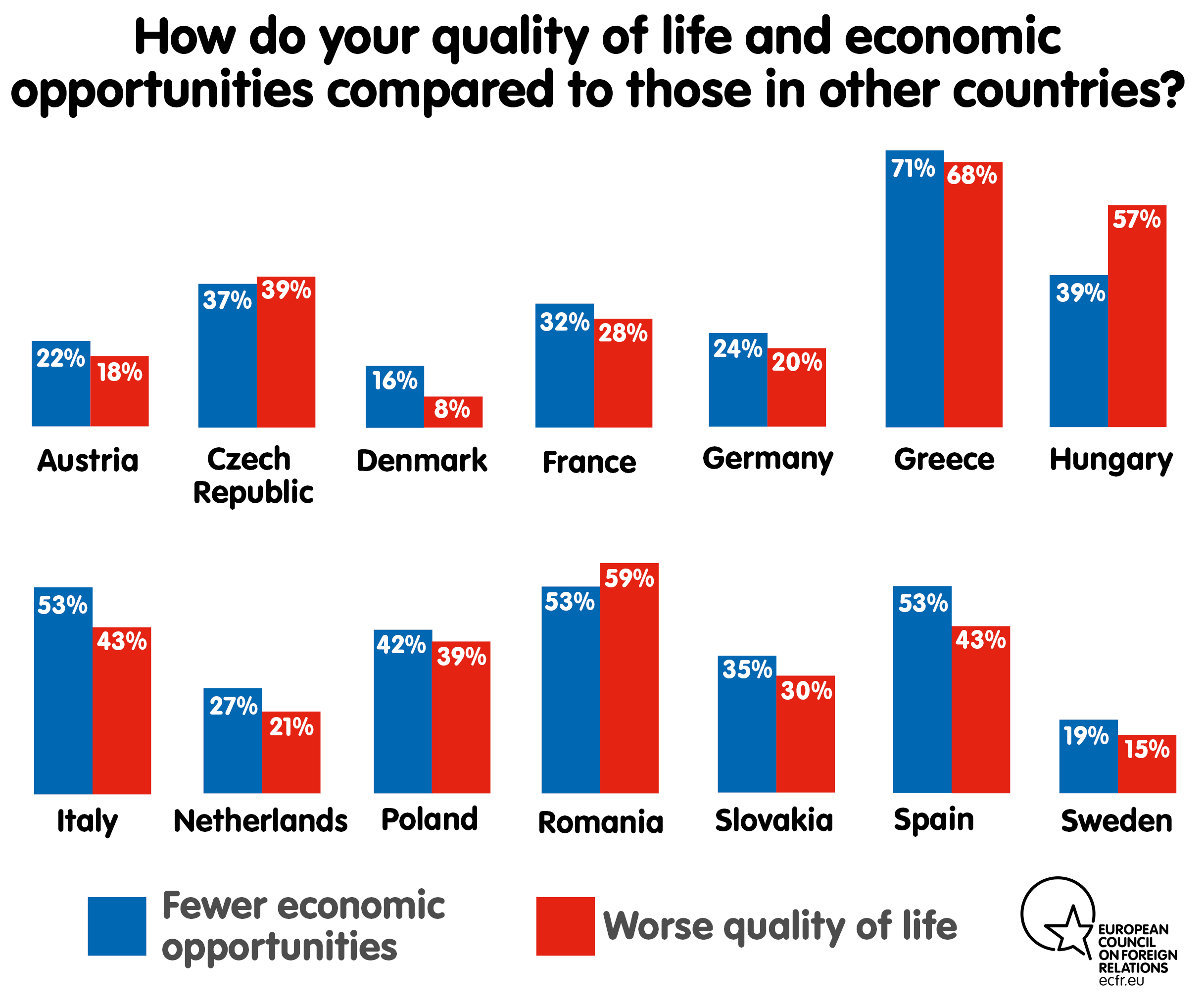

As the chart below shows, countries that see themselves as worse off than others in the EU are among the strongest advocates of a larger, more redistributive budget. In contrast, members of the New Hanseatic League, which feel comparatively well off, see cohesion funds as far less important. Arguments around the Council table in the coming months will simply reflect the differences in citizens’ views. Governments are eager to demonstrate success in promoting a national position in MFF discussions, as this will be hugely important to their creation of a domestic political narrative on the benefits or costs of EU membership.

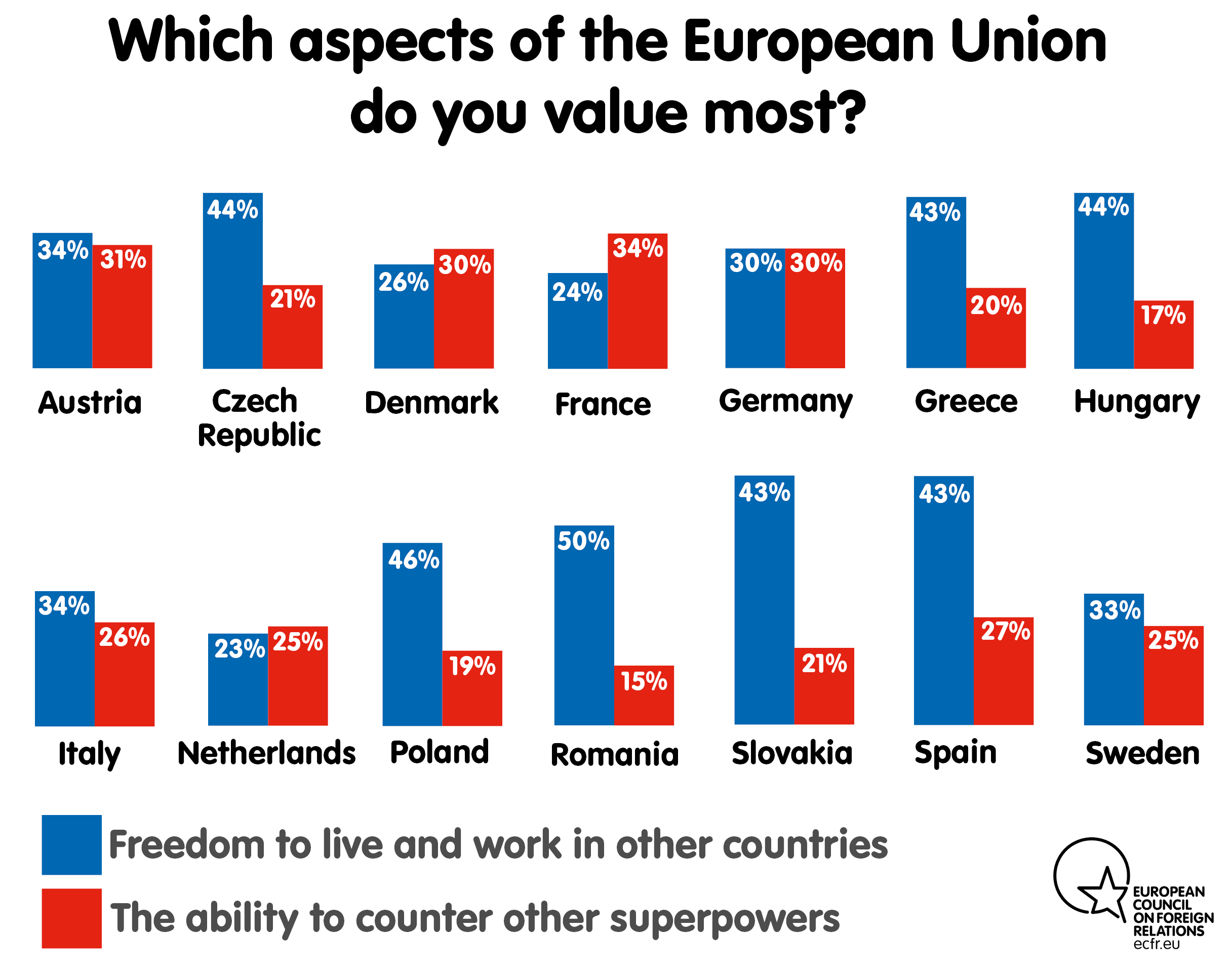

Due to the ways in which large differences between citizens affect member states’ negotiating positions, there is a distinct possibility that the MFF discussions will lead to a decline in the external portion of the budget – making it more difficult for the Commission to achieve its declared aim of strengthening the EU as a global power. The chart below shows which of two aspects of the EU that citizens value most. It is clear that many of them care about the EU as a global actor, but that those who care most are (with the exception of the French) pushing for a smaller overall budget. Therefore, it will be difficult for the member states that are most invested in the EU’s global role to prevent a reduction in the external portion of the budget.

Nobody said that governing a fragmented Europe would be easy. And nobody expects the MFF negotiations to advance much beyond an initial exchange of views this week. But one thing is certain: 2020 will be another rocky ride for the EU. The longer the MFF discussions continue, the longer the delay to the Commission’s implementation of its work programme from the beginning of 2021. Paris would like to reach a deal that will help President Emmanuel Macron justify the energy he has invested in the European project to a domestic audience, with a view to the French municipal election in March. Berlin would like to think that its presidency of the EU, which will begin in July 2020, can focus on the many other challenges the bloc faces. There is a great weight of expectation on Michel’s shoulders to find a way through all this.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.