Spain: Southern Europe’s underrated player

In light of its demographic and economic weight and in view of its location at the crossroads of Europe and North Africa, Spain seems to be underrated in the current line-up of the large EU member states.

Over the 30 years of its EU membership, Spain has changed profoundly. Although it may have been largely disconnected from the rest of Europe during the late Franco period, Spanish democracy has, in more recent times, turned around to embrace Europe. Over the past decade alone, Spain’s gross national income per capita has grown by almost 100 percent, having a massive impact on the lives of Spanish people. USDA-data also shows that Spain’s real GDP has nearly doubled over its three decades of EU membership. By comparison, according to the same sources, the GDP of Italy in 1986 exceeded that of Spain in 2014, but while Spain’s wealth was doubling, Italy’s GDP increased by less than 15 percent.

From being on the margins of EU policy-making, Spain has come into its own since the mid-1990s as an active EU policy-maker with an active stance on political issues facing the EU. The Spain of today seeks to play a central role in political negotiations and deal-making rather than waiting on the sidelines for a moment when it can trade its consent on certain issues for additional benefits. At times it seemed that the country was in fact taking the place of Italy as the most integration-minded country in the South, as Italian EU policies changed with successive Berlusconi governments.

The financial crisis of 2008 hit the country hard. It ended the real estate bubble and exposed clientelist structures that were still in place behind the façade of a modern economy and generally effective public administration. While the Spanish financial sectors received much needed assistance from the EU, the government sought to avoid becoming a “programme country” under the euro zone rescue mechanism. However, the crisis changed the perception of Spain in Europe. From being seen by many as the most “northern” country of the South, the crisis has seen the public image of Spain reduced to the more stereotypical aspects of the “Club Med”.

Taking these developments into account, a comparison of the views of Spanish foreign policy professionals with their counterparts in other EU countries provides some surprising insights. Among civil servants and think-tank specialists Spain is viewed more critically than one would assume in light of the alignment of Spanish economic and fiscal policy to the preferences and practices in Europe’s North. ECFR’s survey among EU policy actors and experts, conducted in the summer of 2015, points to Spain having a comparatively marginal position among the six largest member states of the EU. Spain is rarely listed as a “like-minded partner” by other EU member states and is also absent from the top positions in the lists for countries that member states contact first and/or most, or the lists of member states that are seen as most responsive or easy to work with.

Spain is low on the list of priority member states for both Germany and Poland – a surprising outcome given the strong orientation of Spanish politics towards Germany, or in light of the joint Spanish-Polish attempts to solidify their positions in the group of “large states” since the highly controversial negotiations over the weighting of votes at Nice in 2000. On the other hand, the views of the Italian policy elite reflect an entirely different appraisal of Spain. Next to France, Italian respondents see Spain as the second most like-minded and second most responsive or easy country to work with among the EU members, far ahead of the Italian view of Germany. Spain is also fourth on the Italian list of countries contacted first or most.

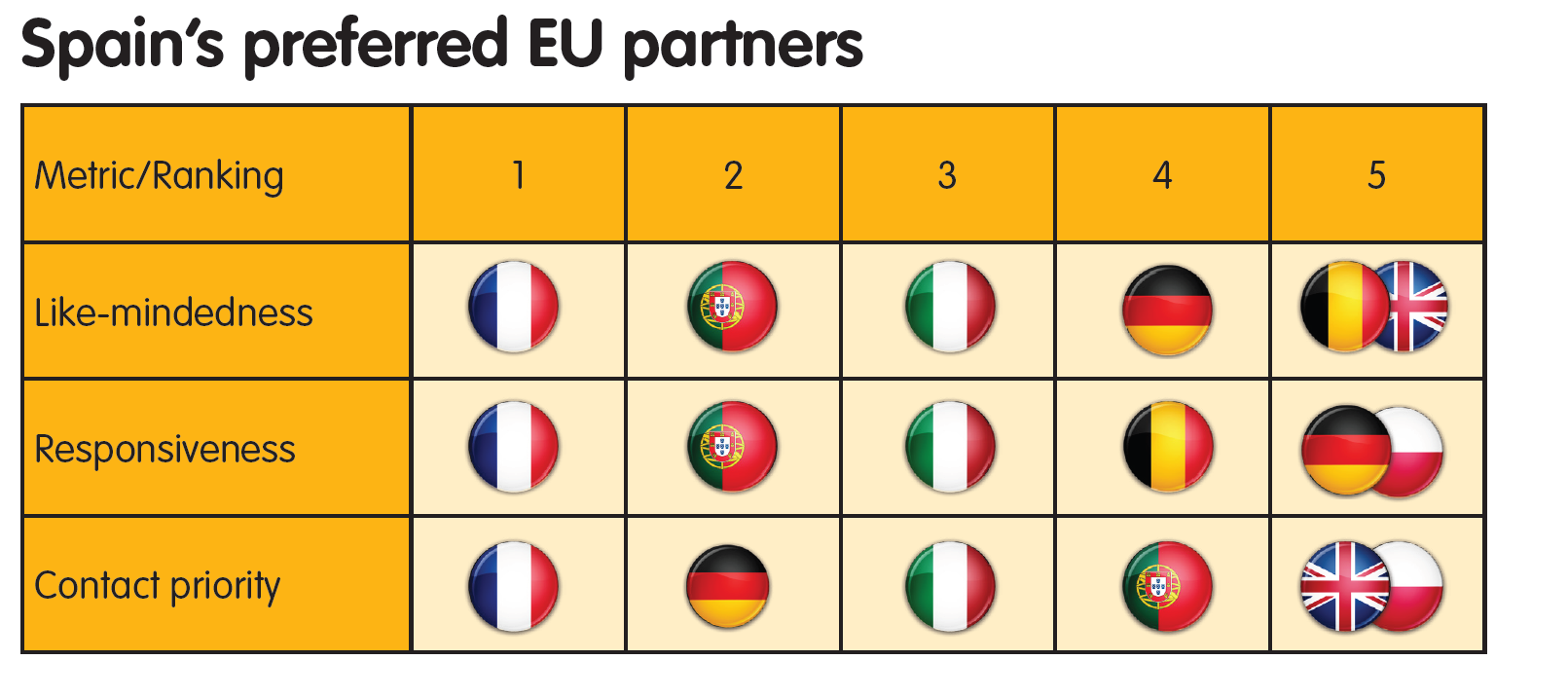

A north-south divide becomes clearly visible in the data concerning the Spanish appraisal of its interaction with other EU partners. In spite of the strong focus of Spanish decision makers on the role of Germany, the Spanish political class shows a distinctively “southern” profile: Asked about the most like-minded other countries, the most responsive and easy to work with partners and the partners contacted first or most, France is at the top of the list on all three questions – the same result as for Italy. For both Spanish and Italian policy professionals, Germany comes second only when asked about the country contacted first or most. Italy is placed third by the Spanish respondents on all three questions.

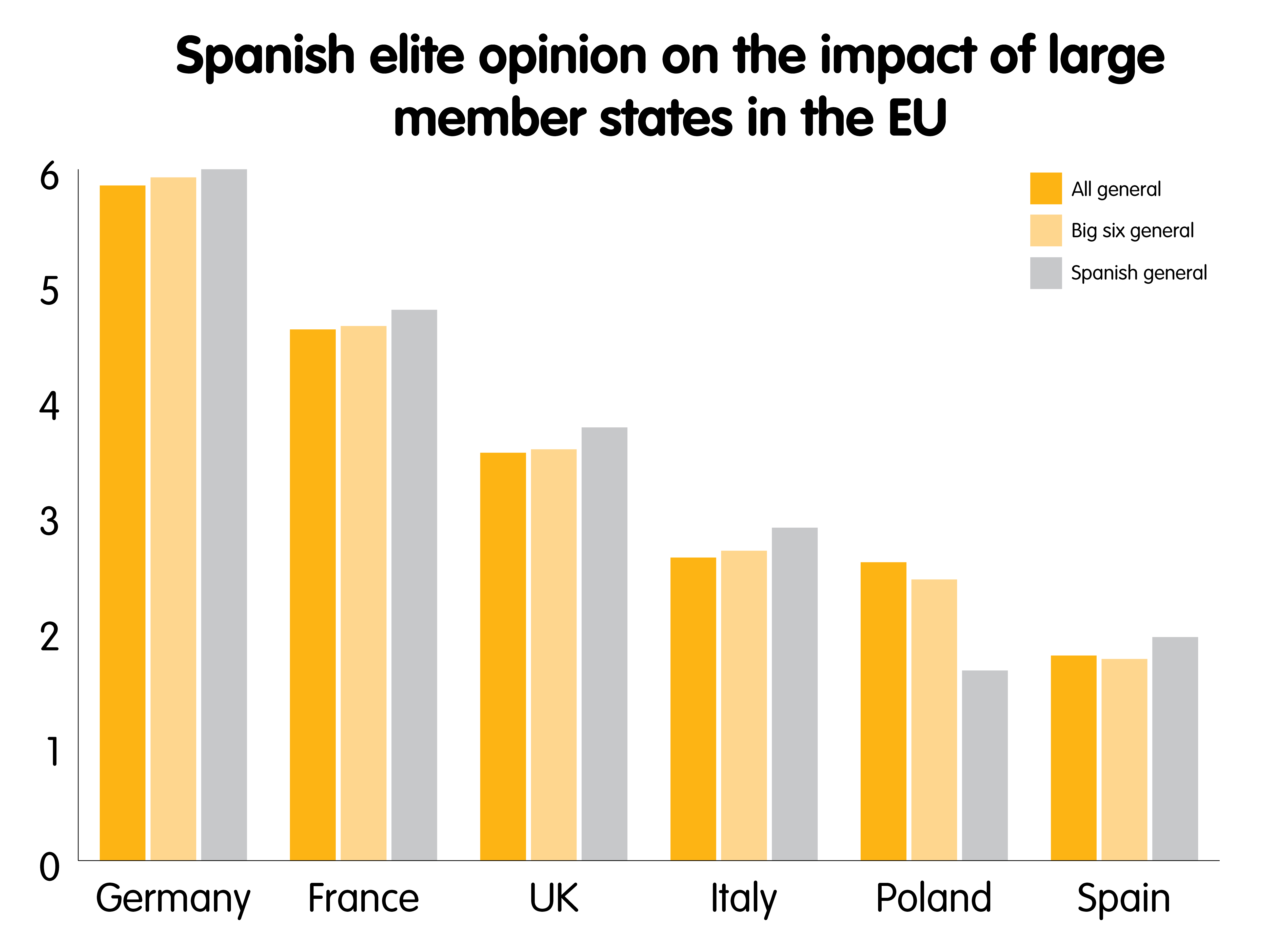

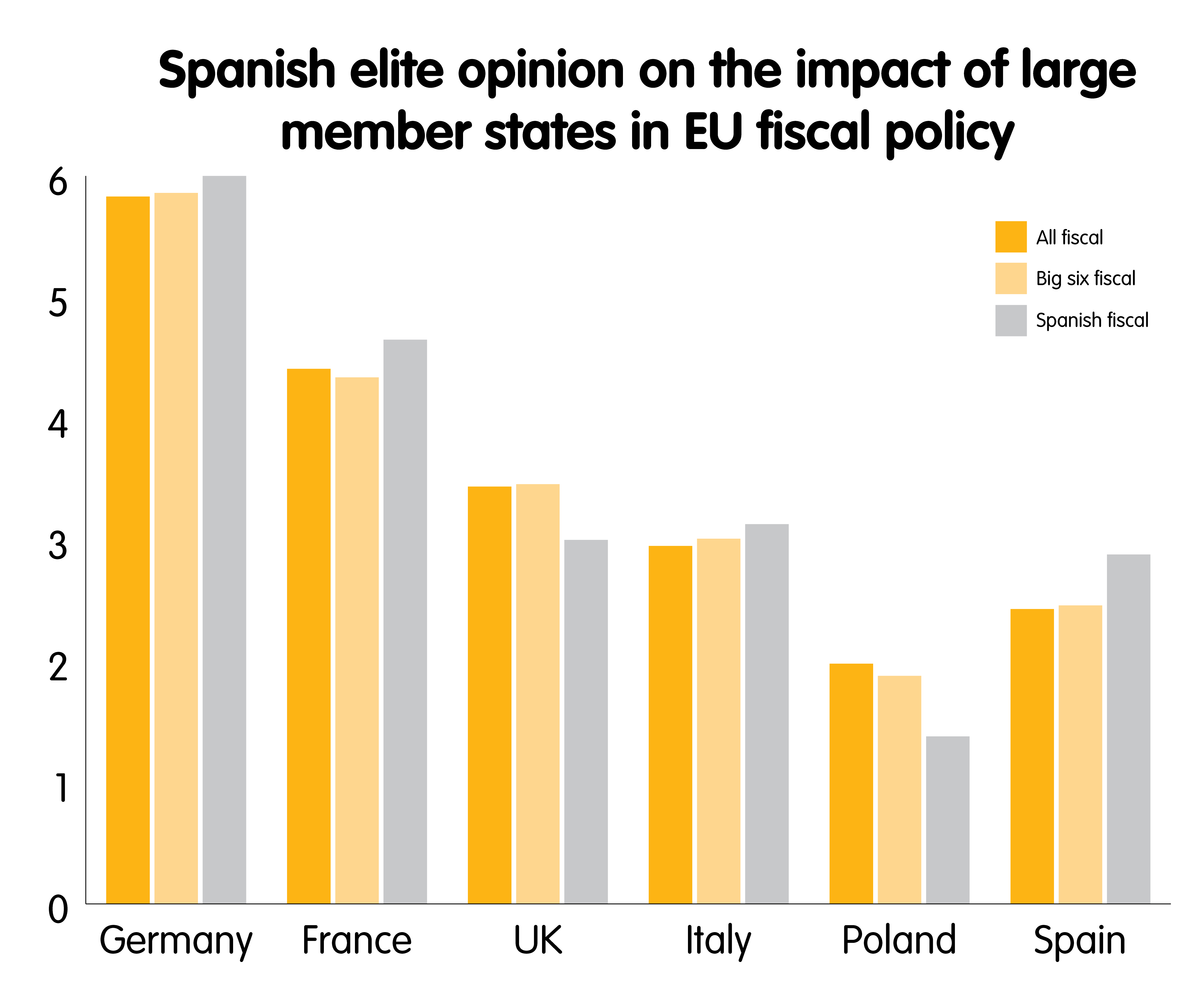

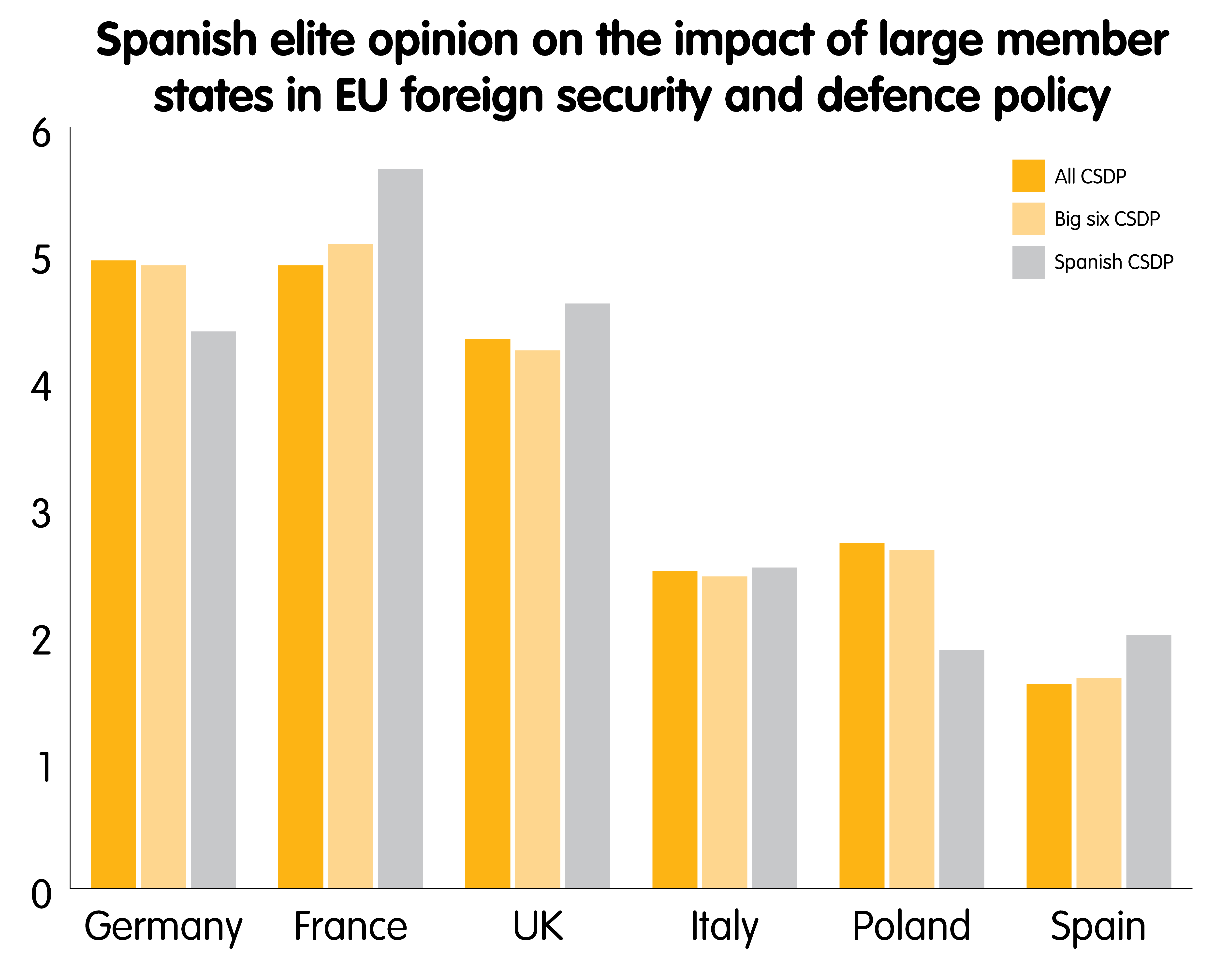

When it comes to Spanish self-assessment of their impact on EU affairs in general, fiscal policy or foreign, security and defence policy, the Spanish respondents rank their country between Italy and Poland in fifth place for all indicators, except for fiscal policy where the Spanish see themselves almost on par with the UK which is placed in fourth. Italy is seen in third here, a view that is shared by the Italian and British respondents, too.

Overall, however, the foreign policy professionals participating in the survey placed Poland before Spain, which means that Poland is generally considered to have a stronger impact on EU affairs than Spain – a striking contrast to the Spanish self-assessment. It also appears to be counter-factual. After all, Spain has not only been a member since 1986, but its population exceeds that of Poland by 8 million and its GDP is 2.5 times higher.

It is only in the area of fiscal policy that Spain ranks above Poland. This corresponds to the ranking of Spain by the Polish policy elite: Spain is seen as having slightly less impact compared to the overall view, and this applies to all dimensions (EU affairs in general; fiscal policy; foreign, security and defence policy), with the Polish deviation from the average being most visible on fiscal policy. It also fits that the Italian policy elite, which holds slightly more positive views on the general impact of Spain than the average, though it is somewhat more critical of Spain’s impact on foreign, security and defence policy.

Respondents from the three largest EU member states differ in their views of Spain’s impact, though the deviation from the average is fairly small. While the French respondents rank Spain slightly higher on EU affairs and on foreign, security and defence policy but clearly lower on fiscal policy, the German policy elite holds the opposite view. German respondents ranked Spain slightly lower on the first two dimensions but somewhat higher on fiscal policy. Among the “big three”, the UK’s position stands out: British respondents rank Spain clearly higher on EU affairs in general and on fiscal policy and slightly more positive on foreign, security and defence policy. This appraisal is partially matched by the Spanish elite’s view of the UK’s impact. The Spanish ranking of the UK is more positive than the average, except for fiscal policy where the UK is clearly ranked lower than is the case by all respondents.

In sum, a gap appears between the political aspirations of Spain’s policy-makers and the policy community. While the leadership seeks to move the country closer to the governance and politics of Germany or Europe’s North, the interaction preferences and patterns as reported by the policy elite in government and the expert community speak for Spain’s southern orientation and network. In short – neighbourhood matters. However, the orientation is not reciprocal: Neither the German view of Spain nor that of the Benelux or the Nordic countries matches the supposed northern orientation of Spanish politics. In its southern neighborhood, the Spanish view is mirrored by that of the Italian policy elite, but much less so by the French.

In light of its demographic and economic weight and in view of its location at the crossroads of Europe and North Africa, Spain seems to be underrated in the current line-up of the large EU member states. Its appreciation among EU governments appears to be shaped by an “eastern bias” among many EU governments and constrained by the fallout from the financial crisis. Over time, both factors will have to be reassessed, or European policy will be locked into misperceptions. In particular, a strategy that is focused on strengthening the political centre of the EU needs to pay attention to the EU policy of Spain. If and when the new balance of the Spanish party system consolidates and the financial crisis is kept under control, Madrid could be a key player in shaping Europe as part of a coalition of pro-integration member states.

***

Data referred to here was gathered as part of the Rethink:Europe project, an initiative of ECFR, supported by Stiftung Mercator. To assess the interaction between EU member states, ECFR conducted its own EU-wide elite survey among foreign and European policy professionals in government, think-tanks, research institutions and specialised media, collecting data between May and August of 2015. The Spanish sample consisted of 23 participants, with about half coming from think-tanks and research institutions, one third being from government and 9 percent from the media. Aggregate data was made available to participants in the fall of 2015; full data and analyses will be published alongside the second call of the survey in the summer of 2016.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.