Shoring up European cohesion: The multiplier effect of political engagement

Only by comprehensively democratising the European project can we meaningfully strengthen European cohesion.

Cohesion: What do we mean?

Current forecasts suggest that anti-EU parties could win around one-third of seats in the May 2019 European Parliament elections. Given the growing support across Europe for ideas and actors that insist on the devolution of powers and competences to nation-states, this hardly comes as a surprise. Yet electoral success for these parties would weaken European societies’ and states’ readiness to cooperate with one another, or what we call “cohesion”. Put another way, cohesion is “the connective tissue of political systems” – a precondition for effective liaisons between various parts of a system. Consequently, a decline in European cohesion would undermine the European Union’s capacity to collectively address common areas of concern, thereby jeopardising the fragile legitimacy upon which it is built.

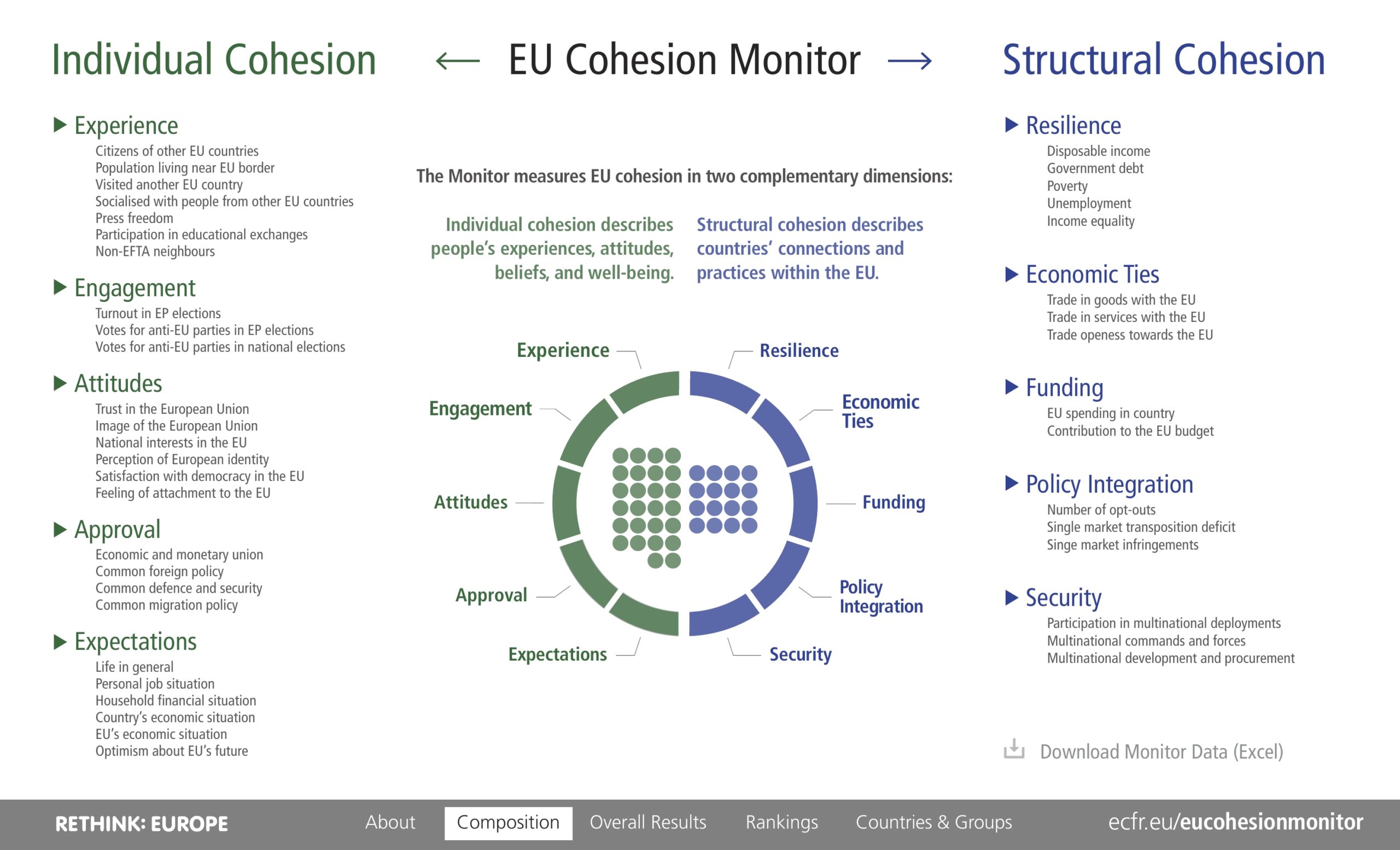

These issues are central to the EU Cohesion Monitor, a quantitative index ECFR created with the support of Stiftung Mercator to measure and visualise the factors that hold Europeans together. The EU Cohesion Monitor groups these factors into two broad categories: structural cohesion and individual cohesion. Structural cohesion includes indicators such as Economic Ties with other member states, Policy Integration, and EU Funding in relation to GDP. Hence, measures of structural cohesion essentially provide an overarching view of the large-scale relationships between member states. Meanwhile, individual cohesion relates to the beliefs and interactions of individuals within member states. It captures citizens’ perspectives on the EU and its policies; their personal interactions with other Europeans; their political engagement (in the form of voting); and their outlook on both the EU’s future and their own. ECFR measures individual cohesion using 26 factors, which it groups into the indicators of Experience, Engagement, Attitudes, Approval, and Expectations. This allows for a granular analysis of societies’ willingness to cooperate with one another.

Capturing political engagement in the EU

As members of an external research team from the University of Groningen, we developed methods of refining the measurement of European cohesion for the EU Cohesion Monitor. Our research focused on individual cohesion, as this is particularly difficult to capture. In comparison to structural cohesion – which is clearly linked to hard data such as that on trade and investment – individual cohesion is relatively abstract and fuzzy in nature. Individual cohesion is difficult to measure due to both a shortage of relevant data and the analytical challenge of interpreting individuals’ belief systems.

EU policies must create new opportunities for citizens to engage with and shape the European project if they are to have a meaningful impact.

These technical difficulties become particularly evident when one considers the indicator of Engagement, which seeks to capture political participation at the individual level. ECFR initially defined political participation as the act of voting, by combining three factors: voter turnout in EP elections, support for anti-EU parties in national elections, and support for these parties in European Parliament elections. Therefore, we tried to broaden the notion of Engagement to include other forms of sociopolitical participation, such as membership of anti-EU parties and involvement in civil society. However, there is no uniform dataset that allows for cross-country comparisons of the former factor. And while there are country-specific surveys about civil society engagement in EU member states, there is no dataset that focuses on political engagement through civil society organisations, let alone the links between civil society and EU decision-making. These limitations prevented us from broadening the Engagement indicator’s definition of political participation.

However, beyond these methodological challenges lies a more fundamental barrier to measuring political participation. Many forms of political engagement at the national level do not have fully developed equivalents at the European level. With some exceptions – such as voting, petitions, and the European Citizens’ Initiative – citizens simply have relatively few opportunities to shape the European project. Most strikingly, individuals traditionally cannot become members of pan-European political parties, which are generally restricted to national political parties. The absence of a common European public space also seriously hampers pan-European mobilisation in demonstrations and other movements. In other words, studies of political engagement in the EU suffer from not only methodological challenges but also a lack of phenomena to analyse.

The multiplier effect of engagement

In this context, EU policies must create new opportunities for citizens to engage with and shape the European project if they are to have a meaningful impact. Indeed, efforts to improve pan-European political participation are not only important in themselves – they are also likely to have a multiplier effect on overall individual cohesion by affecting the factors behind the indicators of Experience, Attitudes, and Approval. For instance, an increase in engagement at the EU level through European political parties or movements leads to a rise in interactions with other Europeans. Beyond this, a rise in engagement can be expected to benefit the EU’s legitimacy as perceived by the individual. After all, as well as providing more effective representation and self-expression for individuals, new avenues for engagement with the European project would help open the EU decision-making process to citizens’ demands. This should correlate with a more positive image of, and greater trust in, the EU. At the same time, improvements in integrating citizens into the decision-making process are likely to increase their support for common European policies.

The recent emergence of political parties that propose transnational electoral programmes provides a promising starting point for discussions on the Europeanisation of political engagement. It remains to be seen whether political formations such as Volt Europa and DiEM25 are as revolutionary as they claim to be. But, in any case, their transnational – and, arguably, radical – ambitions could help address the EU’s democratic deficit and enable the creation of common European constituencies.

Political scientist Vivien Schmidt once argued that only “by improving national citizens’ access to EU decision-making through input and throughput processes can we be sure to shore up legitimacy at the EU level.” Indeed, only by comprehensively democratising the European project can we meaningfully strengthen European cohesion.

Oliver Unverdorben holds a BA in International Relations and International Organisation from the University of Groningen and is currently pursuing a postgraduate degree in International Security and Political Science at Sciences Po and Freie Universität Berlin. He is mainly interested in European integration and EU foreign policy, as well as peace and conflict studies.

Timor Landherr holds a degree in International Relations and International Organisation from University of Groningen. He is currently part of the Rethink: Europe team at ECFR’s Berlin office, where he works on the EU Cohesion Monitor. As well as European integration and EU foreign policy, some of his research interests include security and conflict studies, and (international) political theory.

The authors worked on the development of the EU Cohesion Monitor as part of an external research group for ECFR Berlin. The next edition of the EU Cohesion Monitor will be published on 11 April 2019 on www.ecfr./eucohesionmonitor.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.