German leadership deferred

Germany needs to use its EU Council presidency in 2020 to continue forging cloes ties with and between its partners in the EU to push for comprimises on long-term policy issues.

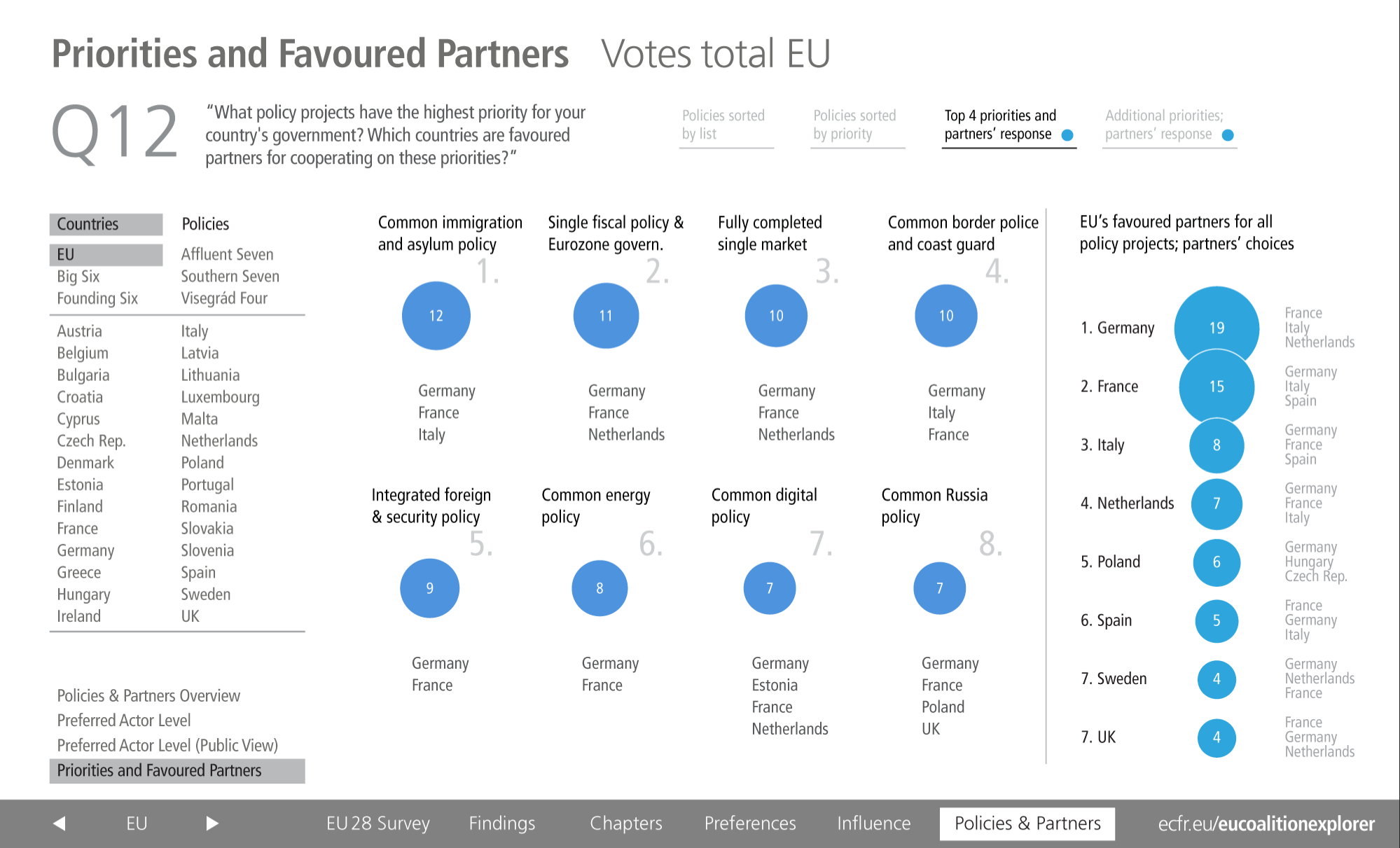

The latest edition of ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer confirms that most EU member states retain their high expectations of German leadership in European Union. Indeed, Germany’s importance can be seen in the fact that it ranks higher than any other country across several categories the survey covers. Member states name Germany as their preferred partner in most EU policy areas, including immigration and asylum, foreign and security, the completion of the single market, and various aspects of economic and eurozone governance. As a result, Germany is also the country member states contact most – and that is most responsive to this outreach. So far, so good.

In principle, the EU27 agree that EU cooperation – be it intergovernmental or supranational, flexible or unanimous – requires decisive German commitment and engagement. A strong EU voice requires a strong German voice. However, domestic developments could prevent Germany from fulfilling the role member states demand of it: that of a predictable, forward-looking partner. In 2019, the coalition government in Berlin has been characterised by a series of internal disagreements on a range of issues.

The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) seemed to have become more unified in the aftermath of a contest to replace Chancellor Angela Merkel as its leader, and to have begun to work through disputes with its sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU). Yet the rift between CDU/CSU and the Social Democrats now appears to be widening – on questions of not only the welfare state but also security and defence policy. In a signal of Germany’s willingness to accommodate France, Merkel used her speech at the February 2019 Munich Security Conference to stress that German compromise is important to establishing a unified EU strategy on arms exports and defence sector cooperation. This quickly prompted resistance from the Social Democrats.

The Aachen Treaty cannot hide the fact that Germany and France have limited common ground on the future of the EU

The Coalition Explorer demonstrates the need for both a functioning Franco-German tandem and a commitment to the strategic partnership among German policymakers. The Aachen Treaty France and Germany signed last January appears to form part of an attempt to revitalise their bilateral relationship at various levels. However, the agreement cannot hide the fact that the countries have limited common ground on the future of the EU – partly due to a lack of a strong intra-German consensus on European policy and structural reform.

Meanwhile, a mixture of domestic developments, external shocks, and challenges within the EU has destabilised many EU coalitions. Brexit has the potential to make the EU more Franco-German or more French – given that it has been French President Emmanuel Macron rather than Merkel who has tried to push the EU agenda forward (most recently by publishing a letter in major newspapers in all 28 member states that calls for the revival of the European project). The prospect of this shift has caused many of the United Kingdom’s traditional allies – among them states outside the eurozone, market liberalist powers, and countries sceptical of strengthening the EU’s social dimension – to intensify their search for new partners in Europe and beyond. At the same time, it has reminded Berlin that traditional alliances cannot be taken for granted.

Germany has responded by attempting to diversify its bilateral relationships within Europe, not least through the Federal Foreign Office’s “Like-Minded Initiative”. This project identifies countries such as Sweden, Finland, and Ireland as allies that might be willing to promote joint European ideas. Germany has also taken an increasingly open-minded approach towards sub-regional cooperation – most visibly, with the Visegrád group (comprising the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). Initially hesitant about the concept of minilateralism, Berlin has now taken a more pragmatic stance.

In February, Merkel met with the Visegrád heads of government to identify their shared interests. As such, Germany has chosen to sit at the table rather than to watch others talking from a distance. This has been especially true when the United States and China have engaged with countries in central or south-eastern Europe. For example, in September 2018, Berlin opted to take part in the third summit of the Three Seas Initiative as an observer, after US President Donald Trump joined the format.

Moreover, policymakers in Berlin have taken (justified) accusations of double standards against them to heart. They have realised that it is unsustainable for them to engage in Franco-German consultations at all political levels while reproaching members of the Visegrád group for exchanging views “behind closed doors”.

Since 2015, European leaders have increasingly contested a narrative that re-emerges in German policy discourse now and then: that German interests are inseparable from European interests. For example, in a statement to mark the beginning of his country’s EU Council presidency in 2018, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz explicitly criticised German policymakers for often failing to make other EU member states feel that their views were sufficiently valued. Meanwhile, some member states have heavily criticised Germany for acting unilaterally and playing power games on issues such as migration and the Nord Stream 2 energy pipeline.

Against this background, Germany’s manoeuvring within the EU very much reflects the tension between the inclusive approach in its foreign policy DNA and its attempts to pursue German interests at the EU level. Merkel and various German ministers have repeatedly emphasised the need to bridge EU divides and to reassure small and medium-sized countries that they are not being pushed to the sidelines.

This tension between national and European is often difficult to address and, of course, not a purely German phenomenon. Yet, crucially, German policymakers have now begun a discussion on the degree to which EU solutions require national compromise.

It remains to be seen whether German political parties will use the European Parliament election campaign to constructively engage with ideas and deals Germany can put forward to make the EU more resilient and more capable of defending the interests of EU citizens. Given the various internal and external challenges the EU faces, it will not be enough for Germany to simply balance east and west – or north and south – by increasing the number of bilateral and minilateral meetings it holds.

The hardest task for Berlin is to push for credible compromises on long-term, strategically important policy issues such as migration and asylum, energy and climate change, defence, cohesion, and social security. It is crucial that Germany uses its EU Council presidency in 2020 to continue forging close ties with and between its partners in the EU, while also putting forward solutions to key policy challenges.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Anna-Lena Kirch has been a research fellow at the ECFR since 2018. She is a research associate at the Centre for International Security Policy at the Hertie School of Governance and works on Polish-German relations in security and defence.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.