Dutch leadership: the end of mere pragmatism?

The Netherlands seems prepared to find a new way of balancing the power of the Franco-German tandem.

In managing its relationship with the European Union, the Dutch government is engaged in an increasingly delicate balancing act. The Netherlands is a founding member of the EU and has long had a substantial majority of voters who favour European integration. Indeed, a recent Eurobarometer poll shows that 86 percent of Dutch citizens would vote against an exit from the EU if there was a referendum on the issue. As ECFR’s Coalition Explorer demonstrates, the Netherlands is also one of the EU’s most influential member states, a pioneer in several EU policy areas, a net contributor to the EU budget, and a major beneficiary of the single market. Yet the Netherlands traditionally has a low turnout in European Parliament elections, shies away from supporting an ever closer union, opposes increases in the EU budget, and is home to influential Eurosceptic parties.

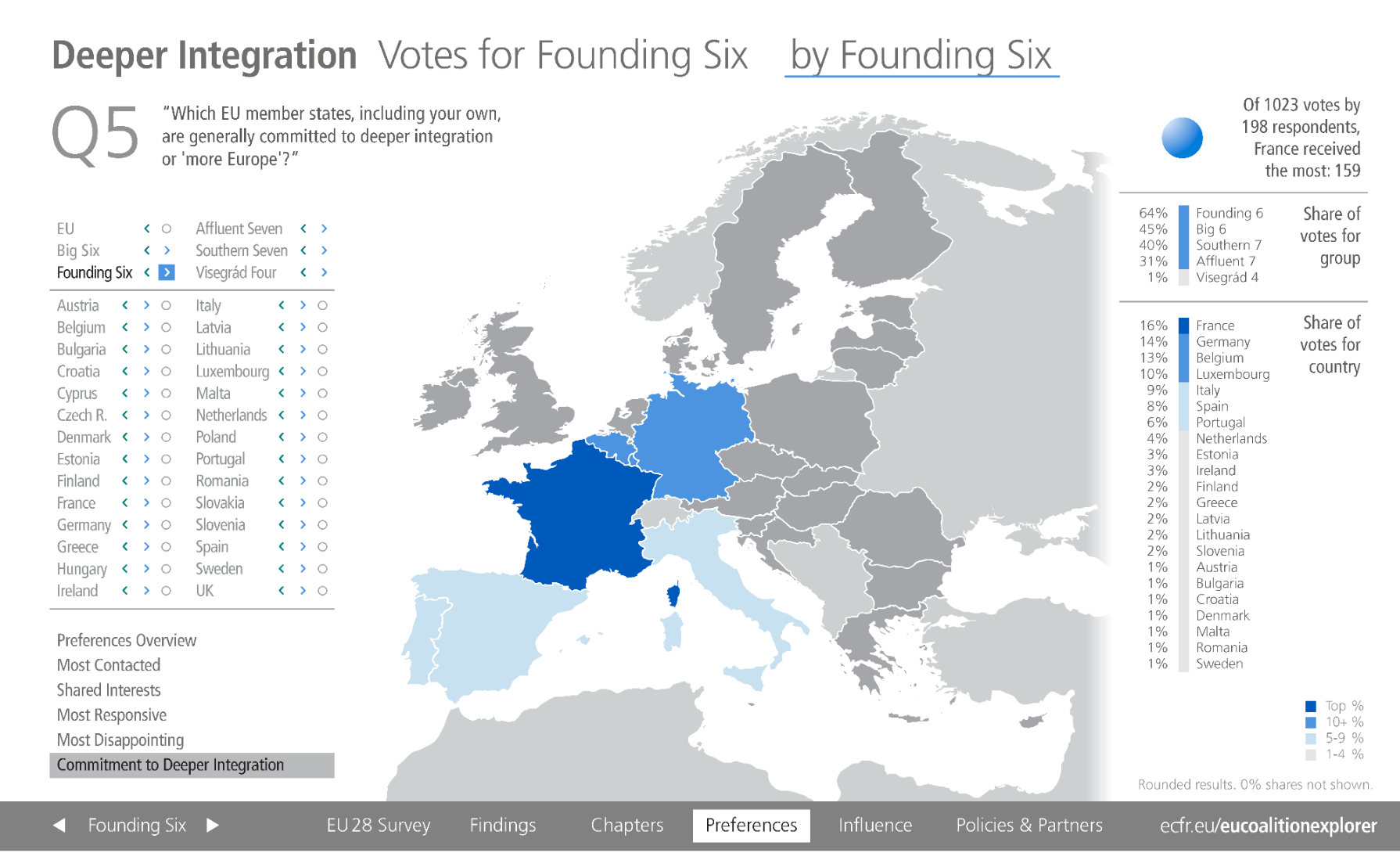

In fact, the Coalition Explorer shows that, among the EU’s six founding members, the Netherlands’ wariness of deeper European integration is equalled only by Italy. And recent domestic political developments make it even less likely that the Netherlands will support ambitious new European integration initiatives. Since the March 2019 Dutch provincial elections – which indirectly determined the composition of the Senate – the anti-EU Forum for Democracy (FvD) has been the largest political party in the Netherlands. The significant growth of the FvD and the continued relevance of the far-right Party for Freedom ensure that the anti-EU contingent in Dutch politics will persist for some time. This is particularly true given that the Netherlands’ ruling coalition lost its Senate majority in the provincial election and now depends on ad hoc alliances to pass new legislation. And the FvD is projected to gain a significant share of the vote in the May 2019 European Parliament election, further strengthening the anti-EU voice in the Netherlands.

Against this background, it is unsurprising that the Dutch government has largely taken a pragmatic approach to the EU. It has done so due to its need to balance between increasingly diverse interests and sentiments. Two out of the four coalition parties – Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and Mark Rutte’s People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) – are pragmatically pro-European. Since becoming prime minister in 2010, Rutte has burnished his domestic and international reputation for pragmatic leadership. He once proudly stated that, as a liberal, he could do perfectly well without any vision.

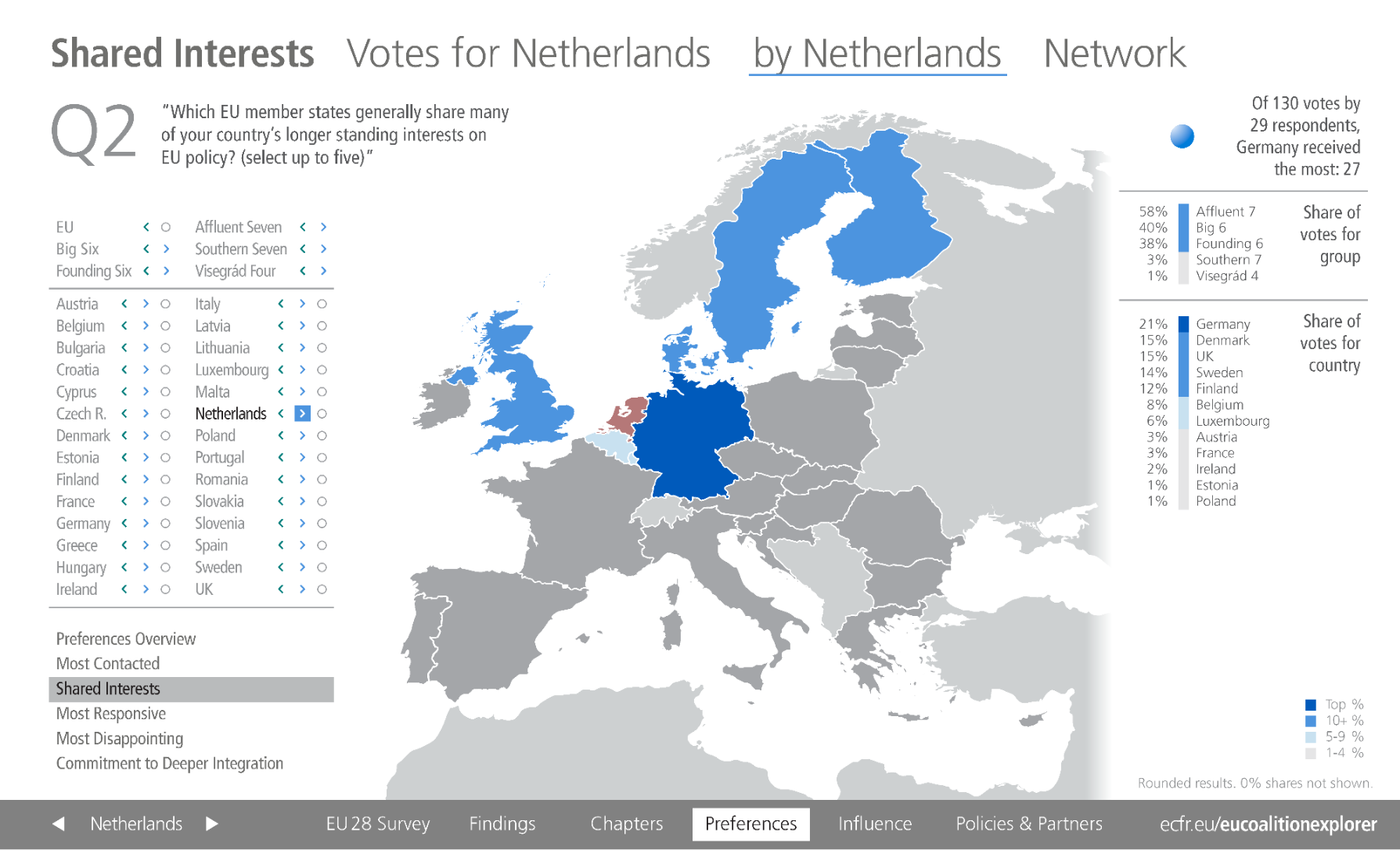

Yet, as a recent Clingendael study observed, the flipside of pragmatism seems to be a rather inflexible and unempathetic pursuit of national interests that does nothing to embed them in a wider European agenda. The Coalition Explorer highlights this problem, arguing that initiatives such as the New Hanseatic League could hamper efforts to increase Dutch influence in Berlin and Paris. Having lost a key ally in the EU following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the bloc, the Netherlands needs to find a new way of balancing the power of the Franco-German tandem. This will be hard to achieve with a narrowly pragmatic approach. Drawing on the history of the European project, France and Germany will likely continue their attempt to deepen integration, be it in relation to defence cooperation or other policy areas. To play a constructive rather than disruptive role in these initiatives, the Netherlands will need to be more than just react pragmatic and reactive.

Rutte seems to have recently become more positive about the EU, admitting that his personal views on the importance of the union have changed. He says that he has developed from being a liberal politician who focuses mainly on the economic dimension of the EU into a political leader who increasingly values the bloc’s political dimension. Although Rutte still thinks that “more and more Europe isn’t the answer to the many problems that people face in their daily lives”, he also believes that Europe should embrace realpolitik. In his February 2019 Churchill Lecture, he stated that “the EU needs a reality check; power is not a dirty word”. He also argued that the union should deal with security issues “in its own geopolitical backyard”, and referred to energy security and the Common Foreign and Security Policy as domains in which there was a demand for more Europe. Moreover, he advocated for qualified majority voting in the case of sanctions.

The speech reflected Rutte’s intention to exercise leadership, and to use the crises the EU currently faces as an opportunity to improve it. Much of the Dutch press interpreted his comments as a signal to his European counterparts that he would be a suitable president of the European Commission or the European Council – a claim he denies. Whatever the truth may be, Rutte’s recent statements suggest that the Dutch government is prepared to go beyond mere pragmatic cooperation.

Niels van Willigen has been an associate ECFR researcher since 2016. He is an associate professor of international relations in the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.