The Young and the Restful: Why young Germans have no vision for Europe

Summary

- German millennials (those born after 1980) appear to be unambitious about reforming the European Union. Their focus is on safeguarding what has been achieved rather than creating something new.

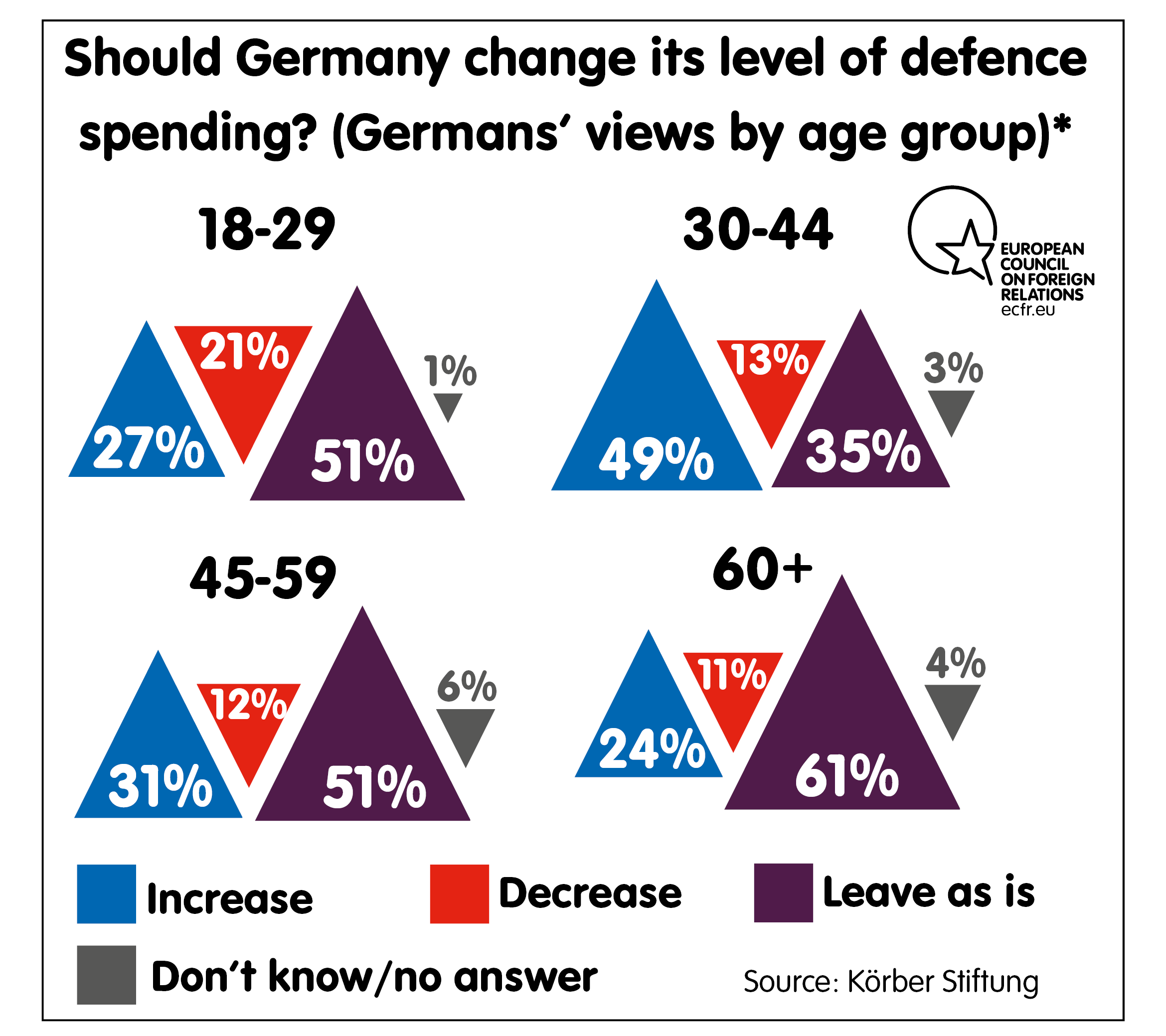

- Data from various surveys and interviews indicate that Germans aged between 18 and 29 hold stereotypically German views on European and foreign policy. They maintain a cautious approach to anything related to the military, and a preference for decision-making that involves the whole EU rather smaller groups of member states.

- Young Germans’ ideal EU would be carefully led by Germany, and focused on European unity, peace, and ecology. It might be more involved in foreign policy, but not militarily. It would also be more welcoming to migrants.

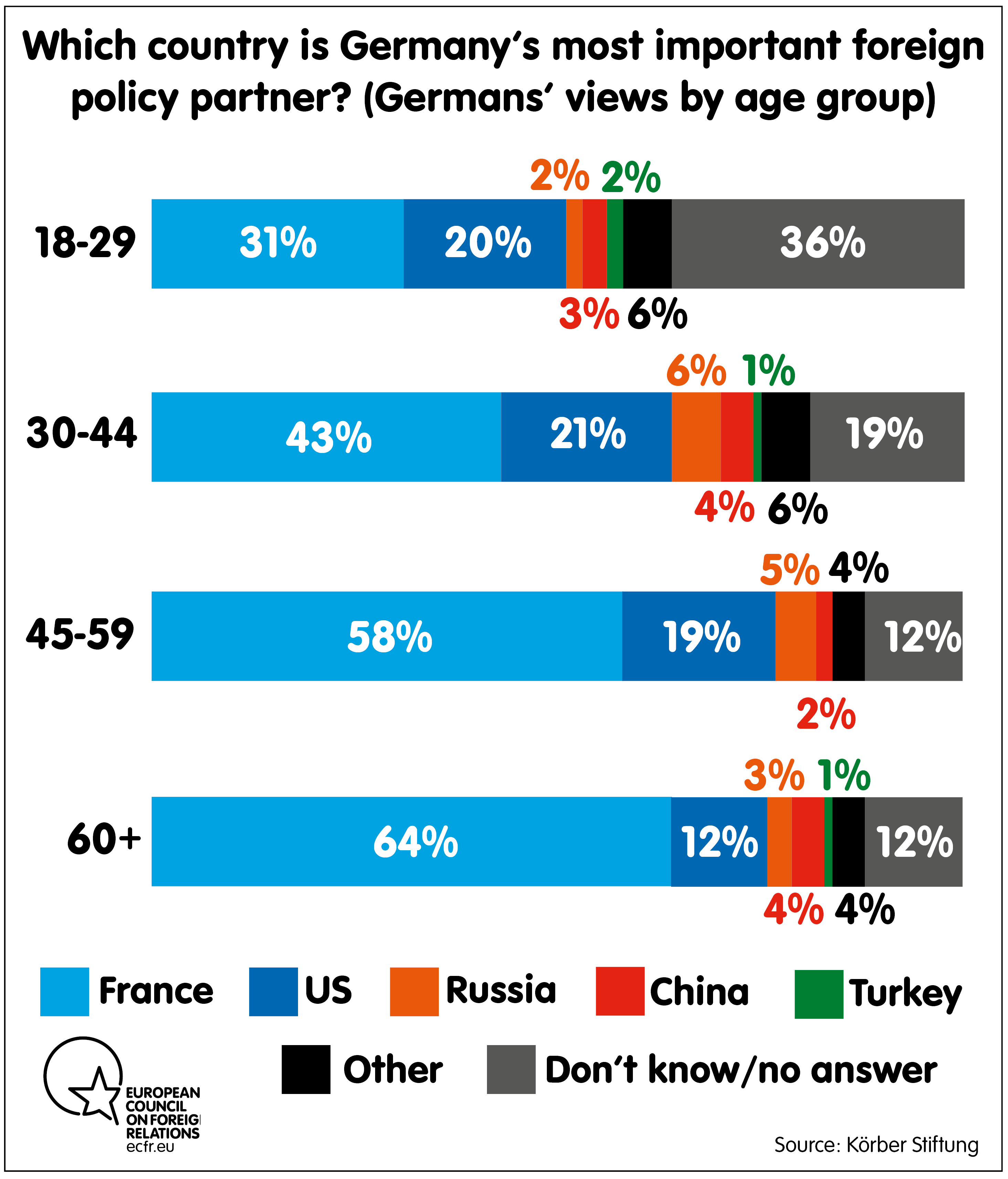

- In Germany, one of the most striking differences between millennials and other age groups is how little importance they attribute to the Franco-German axis. While 53% of Germans see France as their country’s most important partner in foreign policy, only 31% of those aged between 18 and 29 hold this view.

- Discontent among young Germans appears to be sufficiently intense for an inspirational new political movement to capture their imaginations, but there is no sign of such a movement forming.

Introduction

The young are the future! Or so the world believes. Few tropes are used as regularly in democratic politics as references to the young who will determine – and hopefully save – the world of the future, by coming up with new ideas and visions. This hope is particularly present within the European Union, because the EU has a vision problem. In the early decades of the European project, its architects successfully linked their ideal of a unified Europe to initiatives that had a substantive real-life impact on citizens’ lives, such as borderless travel and a common currency. Through this combination of lofty ambition and real-world projects, they secured support from both idealists and pragmatists. But the system no longer functions as it once did. These practical projects have become a reality – along with several of their unforeseen negative consequences – and the European vision no longer shines as bright.

Europe is thus looking to the young for inspiration and a vision of how to develop the project. For this, it particularly needs young people in Germany – the largest, and one of the most pro-European, member states. But unfortunately, as this report shows, young Germans are particularly unlikely to develop visionary new European politics. German millennials are surprisingly conservative and prone to status quo bias. On foreign policy, they hold stereotypically German views – from a cautious approach to anything related to the military, to a preference for keeping the EU together rather than prioritising smaller groups. While discontent among young Germans appears sufficiently intense that an inspirational new political movement could capture their imagination, there is no sign of such a movement forming.

Condemned to visionlessness?

French President Emmanuel Macron has understood more than anyone else that the EU cannot continue with business as usual but is in need of inspiration. Since his election in May 2017, Macron has restored some enthusiasm for the European project. He has presented his vision for Europe – “L’Europe qui protège” – and concrete proposals to achieve it. But Macron knows he cannot relaunch and reform the EU by himself. He has thus extended a hand to Germany – but, so far, no one on the other side of the Rhine has been willing to take it.[1]

This is partly due to domestic political problems. Germany’s September 2017 election led to the longest deadlock in negotiations on a coalition government since 1949. But the country’s relationship with the EU is also more troubled than many outsiders assume, given the constant pro-European rhetoric. It is true that few other countries hold the EU in as high regard. For historical reasons, most Germans have been eager to strengthen the EU and were willing to replace national pride with European patriotism. Germany’s political leadership and education system have given the EU their full support. However, in recent years, amid the financial crisis and discussions about Germany saving Greek pensioners, some Germans have become disillusioned with the European project and begun to express doubt about its future. In the 2017 election, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) became the first right-wing populist party to enter the German parliament since the Second World War, having won support partly through the use of eurosceptic and anti-euro slogans. The AfD’s presence has already changed the tone in political discussions, while political fragmentation into seven parties in the Bundestag has made government formation difficult (a coalition needs an absolute majority in parliament).[2]

Germany therefore has a double imperative to renew the vision of the European project – for Europe’s sake, and for its own. And yet, unfortunately for Macron, Germany is a terrible partner for this task. The country that gave the world the word “leitmotiv” has trouble defining any kind of political leitmotiv for itself, let alone the EU. This is partly by design. Germans take pride in having moved beyond ideology. As former chancellor Helmut Schmidt put it, in a phrase often used in German public discourse: “people who have visions should go see a doctor”. But Schmidt said this sometime in the 1970s, when the horrors of Nazi Germany had occurred recently, and East Germany needed a wall to keep people from escaping the devastating consequences of communist ideology. In other words, Germany’s aversion to political ideologies used to be a sensible choice. Yet it has become a fetish that bans not only ideologies but all kinds of political visions, hampering Germany’s ability to act.

This suspicion of ideology has boosted the stability and efficiency of the political system. But it has also inhibited the creation of new ideas. Germany’s two largest centrist parties have led every government since 1949. Radical or revolutionary ideas have been confined to the political fringe. The German Basic Law, the constitution, favours stability and does not limit the number of times a chancellor can be elected – an unusual provision in the Western world. As a result, Germany, for the second time in 35 years, has a chancellor who is set to remain in office for four terms, or 16 years.

In the 2017 election campaign and subsequent attempts to form a coalition government, German leaders’ lack of vision was particularly on display. The election slogans were empty: from “for a Germany in which we like to live” (the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union, or CDU/CSU) to “you can want future – or do it” (the Greens). Then there was the especially hollow Social Democratic Party (SPD) poster showing chancellor candidate Martin Schulz next to the slogan “the future needs ideas – and someone who can enforce them”. But the SPD was unable to define what exactly these ideas were, contributing to its election debacle. In the end, Germany got another “Grand Coalition” between the CDU/CSU and the SPD, after negotiations on a proposed “Jamaica coalition” – named for the black, yellow, and green of the Jamaican flag, the party colours of the CDU/CSU, the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the Greens respectively – came to nothing. In a very German fashion, the Jamaica coalition did not rupture over diverging ideas for Germany’s future, but because the head of the liberal FDP did not feel that there was sufficient trust between the parties.

Macron has been acutely aware of this German handicap, picking up on this issue in a January 2017 speech at the Humboldt University of Berlin. There, quoting Jacques Delors, he argued: “‘For Europe, we need a vision and a screwdriver.’” Macron continued, “Unfortunately, we currently have a lot of screwdrivers, but we are still lacking a vision.”[3] Yet he saw light on the horizon – in the form of the next generation. Near the end of his speech, Macron added: “The European construction was initiated by men of experience, instructed by the tragedy of the European civil war. It now relies on young people like you, a generation that knows what a crisis is, that discovers the turmoil of the world and the violence of history.”

This may sound like the kind of typical appeal to the young that can be found in almost any political speech. But the reason why Macron’s comment may have been more than the usual empty rhetoric is that, across Europe, disillusioned young people have begun to take politics into their own hands.

A German “youthquake”?

It started slowly. In summer 2016, the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the EU provided yet another demonstration of the political weakness of my generation: 29% of British voters between the ages of 18 and 24 voted for Brexit – compared to 64% of those over the age of 65.[4] As we know, the old won against the young.[5] A similar dynamic was at play in the US presidential election later that year.[6] But, following these events – and partly because of them – something has started to change in Western politics.

In June 2017, when Brexit beneficiary Theresa May called a snap election to cement her position as prime minister, many young people rallied behind Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, contributing to the Conservative Party’s loss of its parliamentary majority.[7] “Youthquake” – defined as “a significant cultural, political, or social change arising from the actions or influence of young people” – became Oxford Dictionaries’ word of 2017, a year that saw the 39-year-old Macron become president of France and a 31-year-old become Austrian chancellor.[8] This trend is continuing in 2018, with US teenagers taking on the federal government over gun control. The internet may have turned millennials (people born after 1980 or thereabouts) into punchlines but, increasingly, the millennial generation is driving political change.[9] But could something similar happen in Germany?

Germany has the highest average age – 44 years – of any European country, with 21% of Germans older than 64 and only 13% younger than 15.[10] This has political consequences. In 2013, for the first time, more than half of all registered voters were older than 50. In the current political landscape, a party would be able to become the second strongest faction in parliament merely by winning the votes of all Germans who are 71 or older. In contrast, a party supported only by all voters under the age of 21 would not enter parliament.

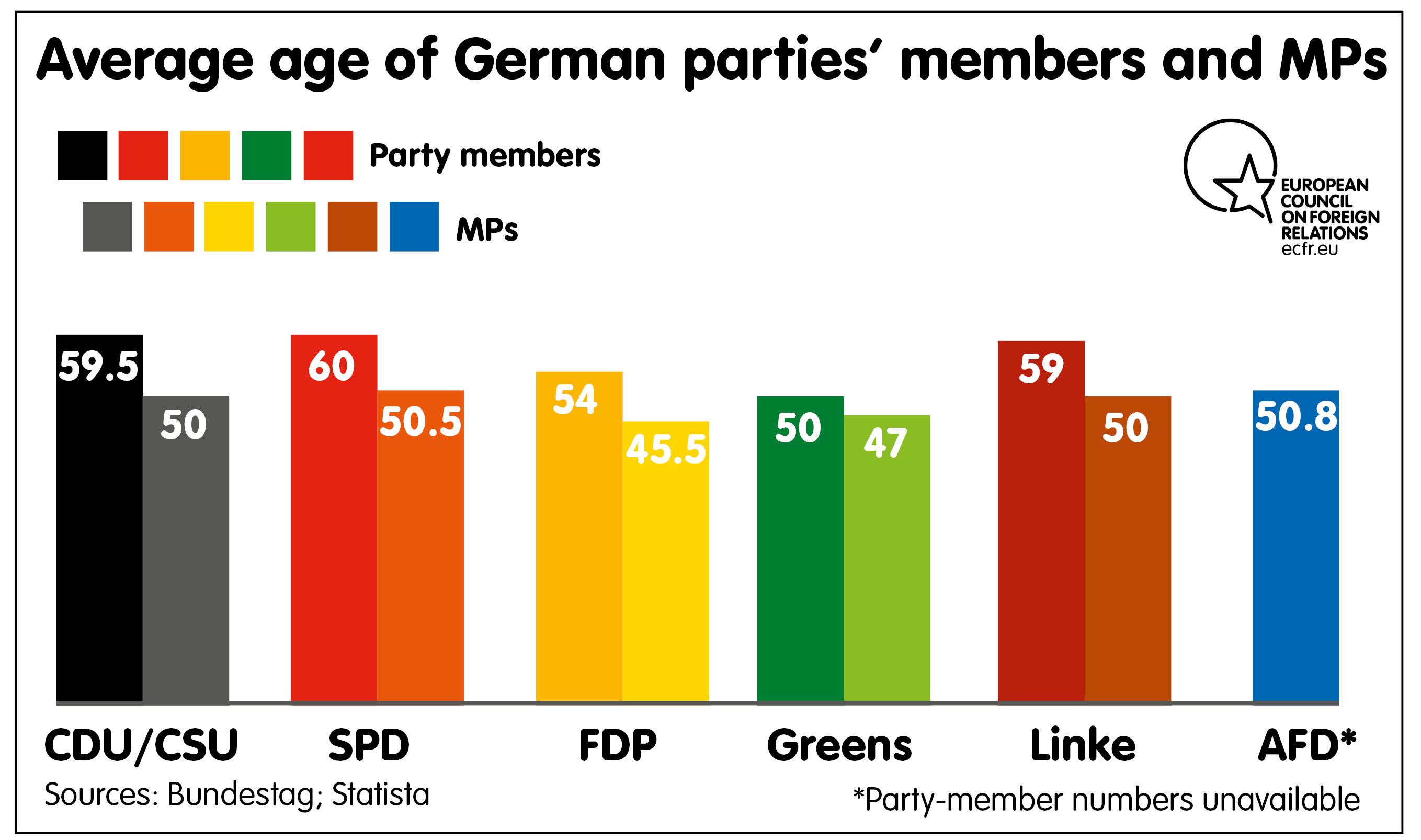

Unsurprisingly, the baby boomer generation – people born before 1965 – occupies nearly every key executive position. Chancellor Angela Merkel is a baby boomer, as is her erstwhile rival Schulz. In September 2017, the youngest member of the cabinet was 57. The typical member of parliament is just short of his or her 50th birthday; the average party member is even older.

And yet there has been some hope of a German youthquake. Few people knew of Kevin Kühnert – head of Jusos (Young Socialists), the youth organisation of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) – before January 2018. The 28-year-old quickly rose to fame by leading his party’s opposition to the coalition deal between the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and the SPD, coming close to toppling it.

Much of the German media initially covered this youth uprising by infantilising Kühnert. For example, journalist Sibylle Krause-Burger wrote: “the baby fat is still there – you can still see the little boy in him.”[11] The wider media generally referred to him as “Kevin”. Meanwhile, older politicians appearing on talk shows addressed him using the informal “du” instead of the formal “Sie”. The Jusos’ movement was dismissed as a “dwarf uprising” – a label Kühnert, who is 1.7 metres tall, cleverly embraced.[12]

After being repeatedly asked questions about clearing his political views with his parents or living in a flat share, he tweeted that he would answer them once Merkel had been asked about whether she licked the top of yoghurt pots.[13] In the tweet, Kühnert used the hashtag #diesejungenleute (“these young people”), which quickly began trending as thousands of young Germans shared their stories about being treated dismissively due to their age. A poll revealed that an extraordinary 83% of Germans between the ages of 18 and 29 believed their generation was not sufficiently represented in German politics.[14] On the homepage of its website, Jusos even provide a guide to responding to age-based criticism.[15]

As a result of this debate, media coverage of youth politics became more favourable, and political pressure for change began to build.[16] Suddenly, there were calls for an age-balanced cabinet – including from the Junge Union, the CDU/CSU’s youth organisation. Merkel felt compelled to give a cabinet post to the 37-year-old Jens Spahn (incidentally, one of her biggest critics).

It looks as though the German millennial generation, having been told all their lives that they were the minority, have begun to embrace that label – and are demanding affirmative action. But what would change if German millennials alone decided on the EU’s future?

German millennials

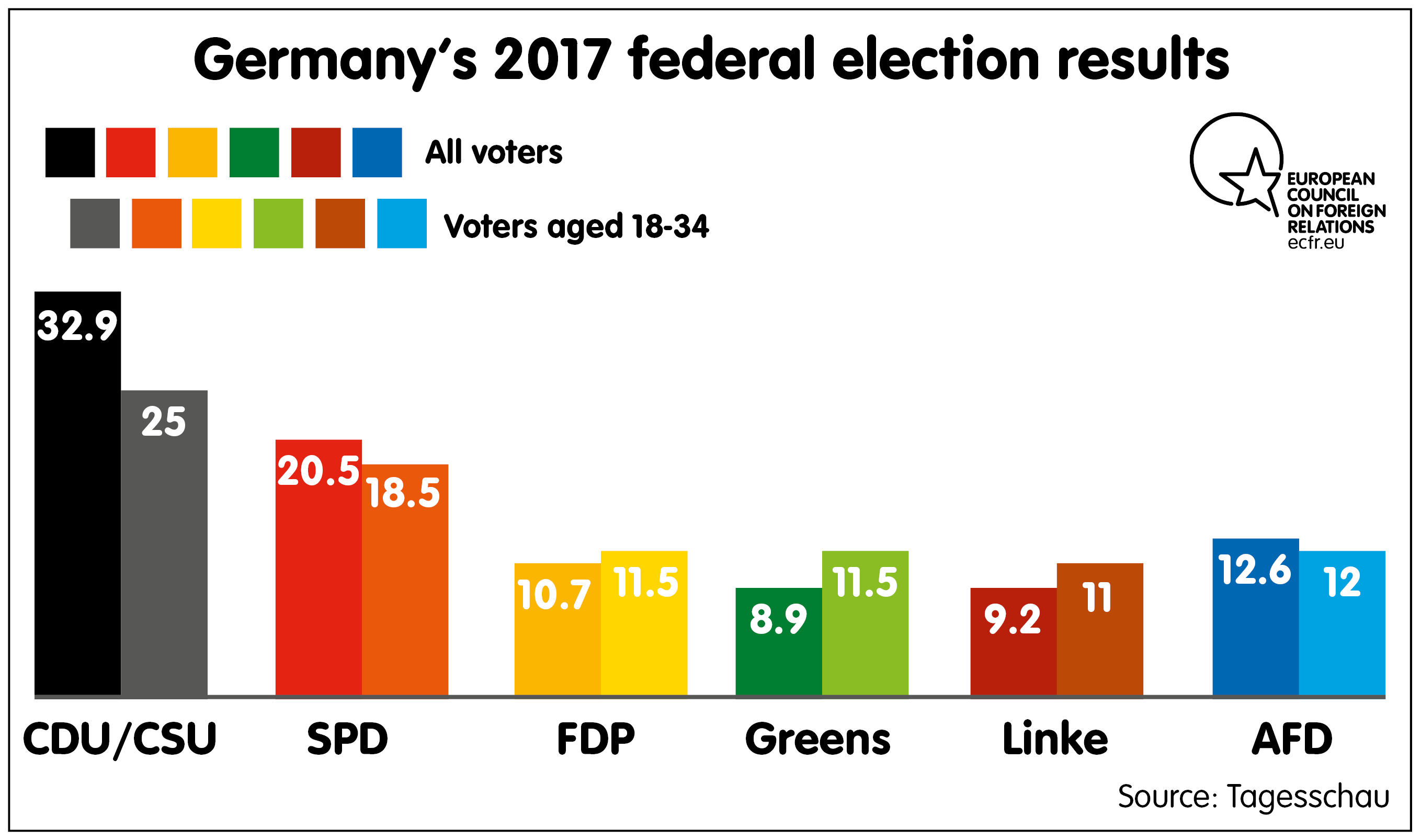

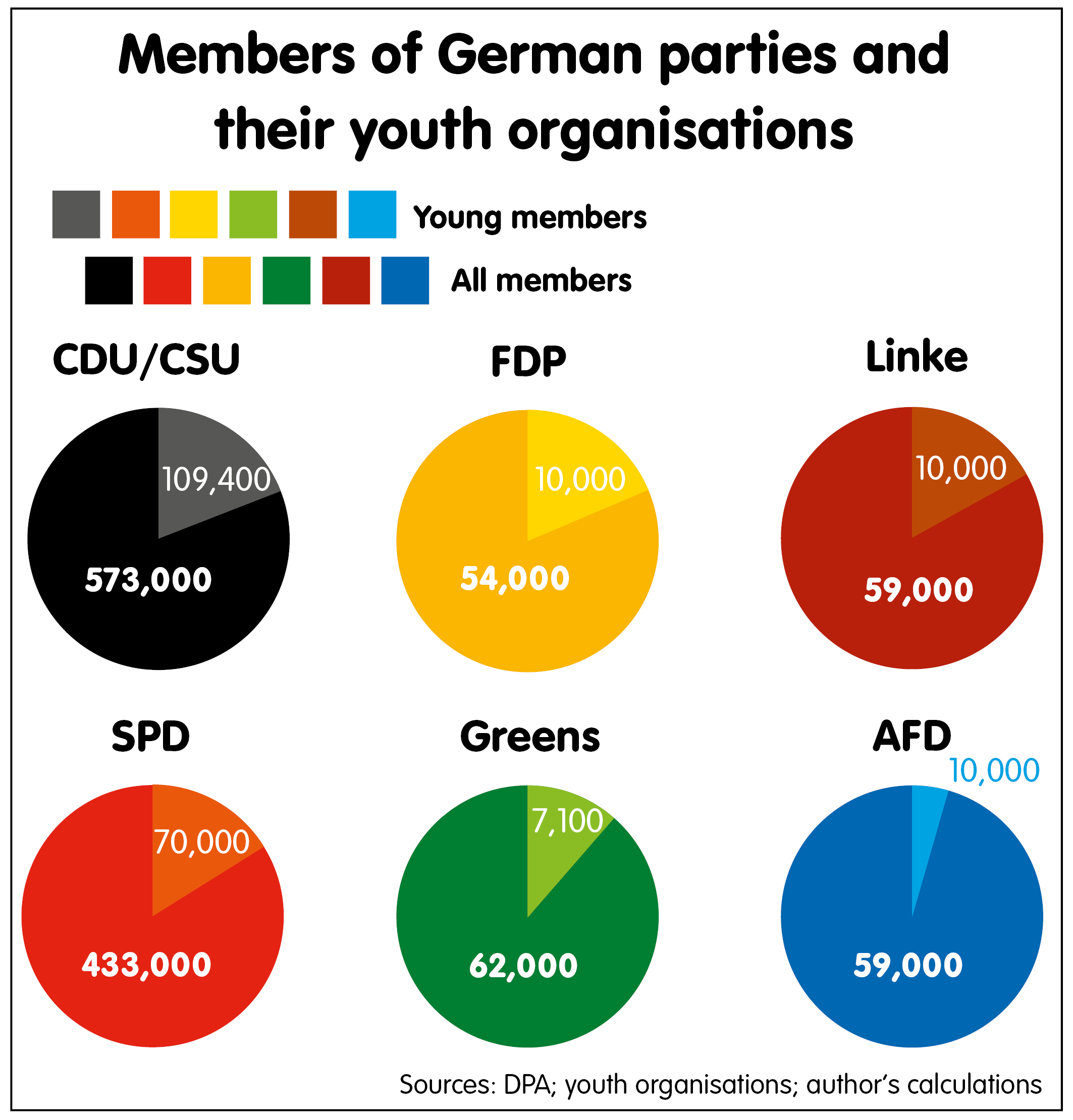

Conventional wisdom has it that young voters are more radical than their elders. But German millennials are surprisingly conservative. The conservative CDU/CSU, in government since 2005, gains a larger share of votes from those aged 18-34 (25%) than any other party. And while in the 2017 election both “Volksparteien” – the CDU/CSU and SPD – gained fewer votes than in the previous election, their losses were least severe among young people.

The CDU/CSU also has the largest youth organisation of any German party, both in absolute terms (with 109,400 members) and as a proportion of the party (19%). The liberal FDP has the second-highest proportion of young members.

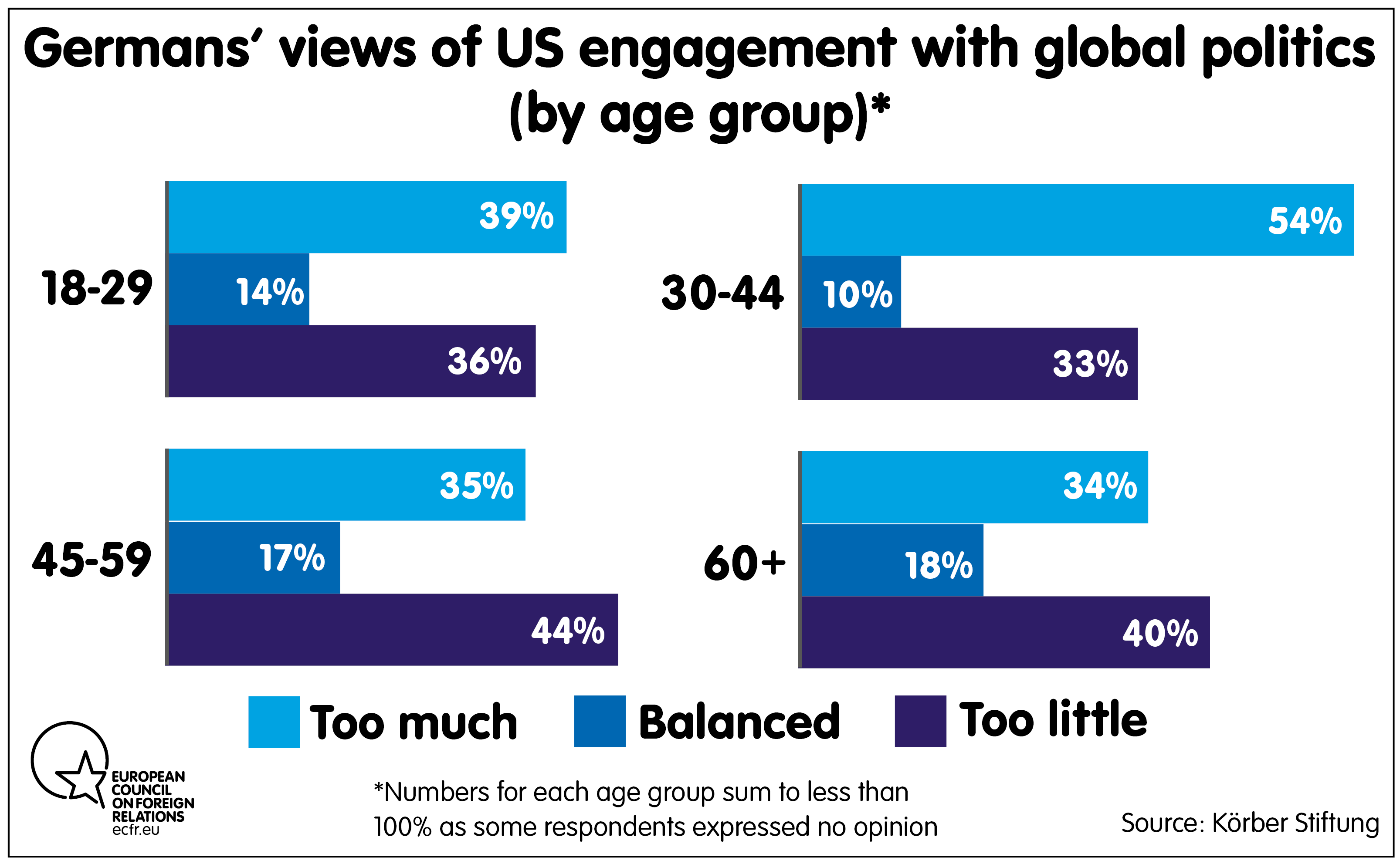

Maybe German millennials’ formative experiences can explain this apparent conservatism? Having lived through major events at roughly the same age, members of a single generation have things they understand uniquely well and things they miss. And although people may change their political views as they age, members of a generation share experiences that colour their perspectives. These generational divergences can be observed in polls. For instance, 15% of Germans believe that the United States plays a balanced role in global affairs, the rest are almost evenly split on whether the country engages with the rest of the world too little or too much. But there are important differences between generations. Most of those aged 44 or younger, particularly those between the ages of 30 and 44, believe that the US is too dominant. Of course, this is the generation for whom the 2003 Iraq War (with all its negative consequences) was a major event in their formative years. A 35-year-old German experienced the onset of the war as a 20-year-old – and probably protested against it.

For those born during 1980-1985, some of the major events of their teens and early twenties include the Kosovo War, 9/11, and the beginning of the “war on terror”. For those born in 1990 or later, they were the 2003 Iraq War, the financial and euro crisis, and the Arab uprisings and subsequent wars in the Middle East. Significant EU achievements such as the establishment of the Schengen Area and the euro happened so early in millennials’ lives that most took them for granted, being unable to remember the time before they occurred.

Hence, young Germans’ apparent conservatism appears to be first and foremost a status quo bias. This fits with the results of the Shell Youth Studies, a series of surveys commissioned to document the attitudes, opinions, and expectations of young Germans. The titles of the last three studies are telling: 1994: “generation cool disinterest”; 2002 “generation cuddle”, and 2010 “generation Biedermeier”.[17] The title of the last study refers to the period between the Congress of Vienna and the European revolutions of 1848, during which the middle class retreated into the security and predictability of the home. “A fear of crisis has become the central youth feeling”, one of the study’s authors argued.[18]

One poll, however, suggests that young Germans may yet be good for a few surprises. It seems many young people are voting for status quo parties without real conviction. Despite predominantly casting votes for the CDU/CSU or the SPD, when asked to name the party that best represents their generation’s interests, 23.2% of young people identify the Greens, while 19.5% say Die Linke, 13% the FDP, 11.4% the AfD, 11% the CDU/CSU, and 9.1% the SPD.[19] These inconsistencies suggest that there is substantial political dissatisfaction among young Germans that a new political movement could tap. The speed with which the young took up the issue of what writer Sascha Lobo calls “rampant generation contemptibility” suggests that they have real grievances.[20] That more than two-thirds of young Germans feel they are not represented in politics is worrisome – but it also points to an opening for politicians able to connect with the young.

Young Germans’ EU

Polls and interviews conducted for this study suggest that there is no one vision of Europe that unites young Germans. While a few German political forces have sweeping visions – such as the FDP Junge Liberale’s federal Europe, and the AfD’s return to the trade-only logic of the European Economic Community – most only have ideas for “screwdrivers”.[21] Like their parents, the young think rather small. The SPD’s youthquake, for instance, did not produce a grand vision; Kühnert’s leitmotiv was “let’s be dwarfs today, so that we can be giants tomorrow”. As one journalist commented, “not even Helmut Schmidt would have sent him to the doctor” for that type of vision.[22] Still, polls –particularly the Körber Stiftung’s 2017 Berlin Pulse poll, when broken down by age groups – and interviews with young German politicians allow one to find out what Germany’s Europe policy would look like if it was determined by the young.[23]

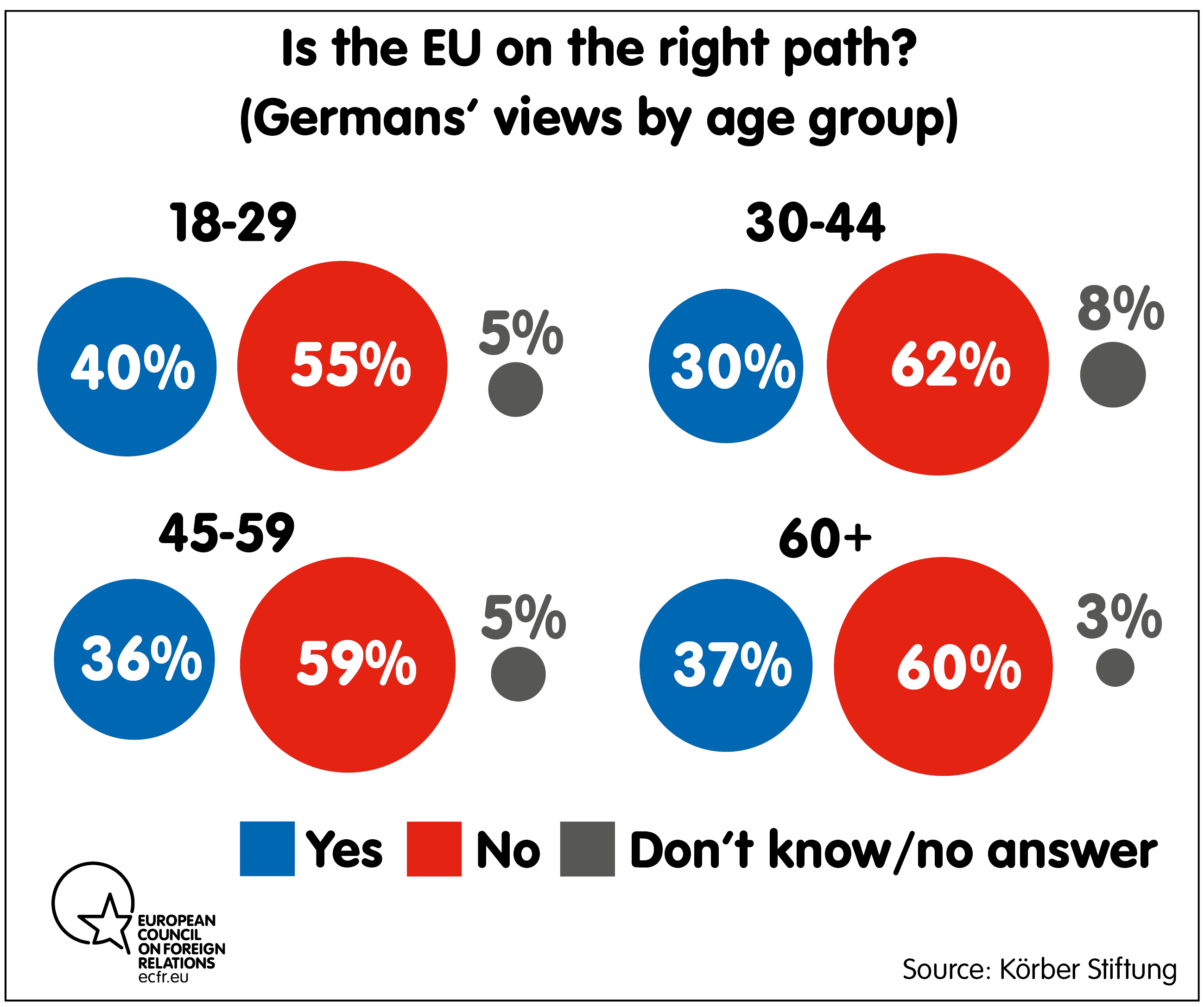

Overall, young Germans remain committed to European integration, with 30% of them regarding Europe as “the only project for the future” and 38% seeing it as “a necessary construction”. Both figures are among the highest in any European country.[24] Yet young Germans are concerned about the EU’s direction. Although they are more likely than other age groups to argue that the EU “is on the right path”, more than half of them worry that the EU is not moving in the right direction.

Conception of the EU, allies, and enlargement

Sociologists argue that, in their professional lives, German millennials value flat hierarchies and dislike top-down approaches.[25] In European politics, this translates into a preference for collaboration with all EU member states rather than partnerships such as the Franco-German alliance. Similarly, they appear to oppose a division between “core” and “peripheral” EU countries. In fact, one of the most striking differences between millennials and other Germans is how little importance they attribute to the relationship with France. While 53% of Germans see France as their country’s most important partner in foreign policy, only 31% of those aged between 18 and 29 hold this view. This is surprising given the election of Macron, who is popular in Germany, including among the young. At the same time, more than one-third of young Germans could not identify Germany’s most important partner in foreign policy, pointing to a general sense of uncertainty.

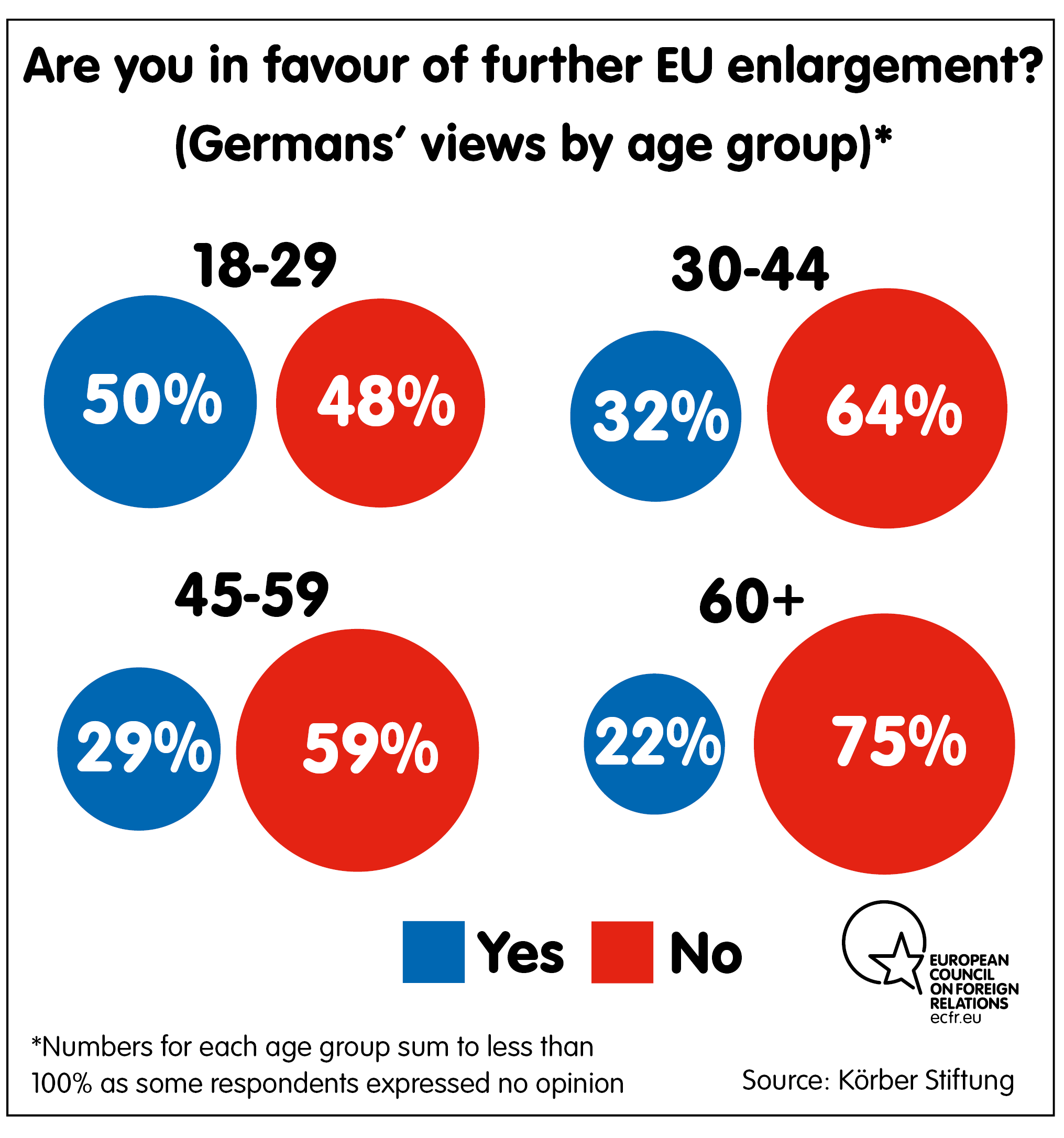

In Germany, there is much greater support for EU enlargement among the young than any other age group (all age groups, however, oppose Turkish accession). However, though supportive of enlargement, many young politicians interviewed for this report recommended that the EU “take a moment to reform itself” before accepting more members. Millennials actively engaged in German politics generally see internal EU reform as important, with many stating that the organisation can only move forward if it reforms its institutions. Several interviewees suggested that the EU should gradually shift away from decision-making based on unanimity and towards majority voting, including in foreign policy. They also supported a system in which the organisation has more power to reprimand member states that violate its rules.

European defence and security

Although the overwhelming majority of German millennials have no direct experience with war in Europe, 80% of those aged between 15 and 24 believe that peace on the continent is the EU’s greatest achievement, and efforts to address climate change as the organisation’s second most important accomplishment.[26] Young Germans are relatively supportive of German engagement in international crises – in fact, those aged between 18 and 29 are the only group in which the majority supports more engagement in foreign policy.

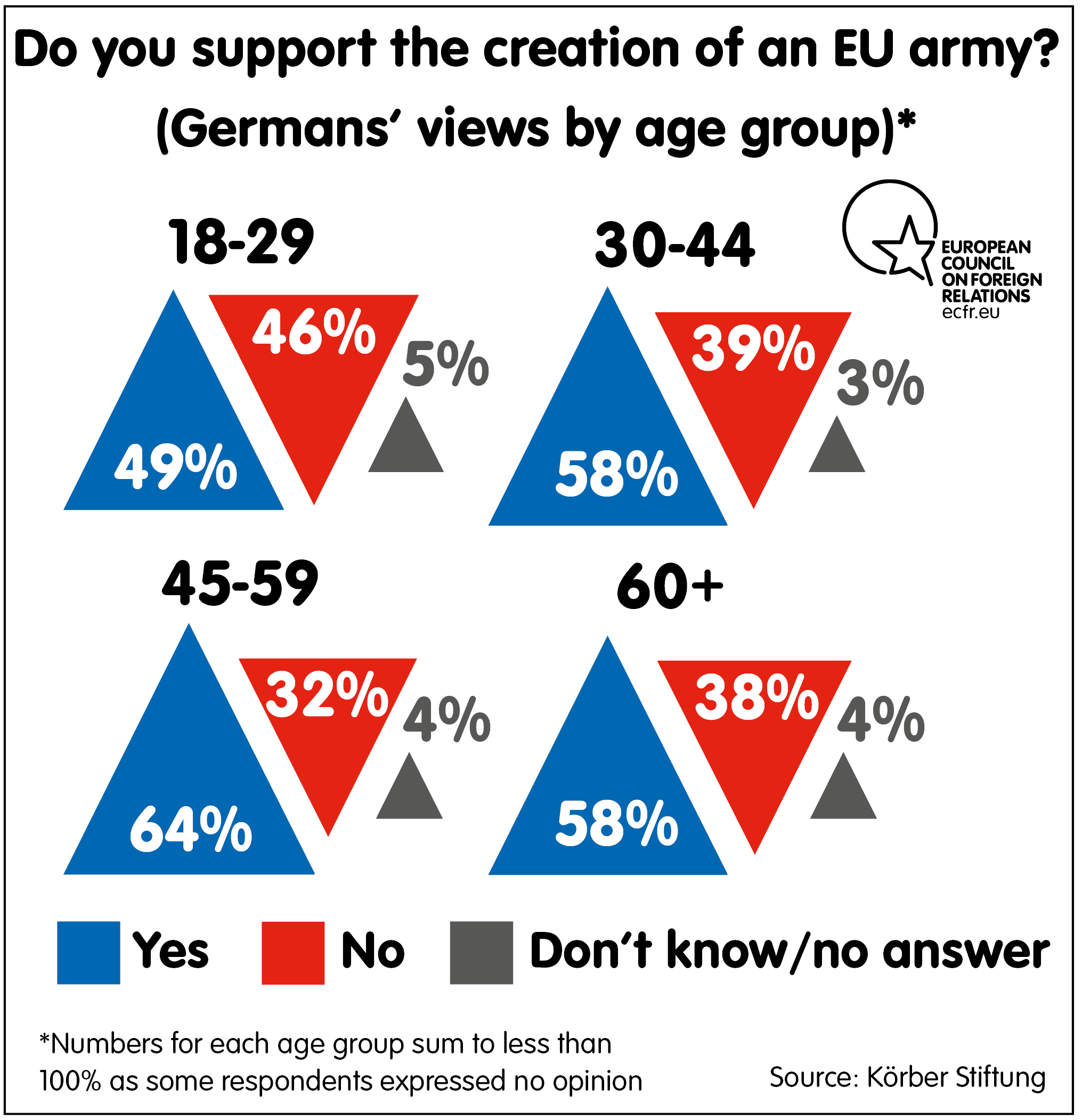

However, this increased engagement does not include greater military engagement. Although 58% of all Germans like the idea of a European army, less than half of those aged between 18 and 29 hold this view. In the same vein, 21% of German millenials back a decrease in Germany’s defence budget, compared to 12% in the other age groups (the majority advocate no change in spending).

Germany’s role in the EU

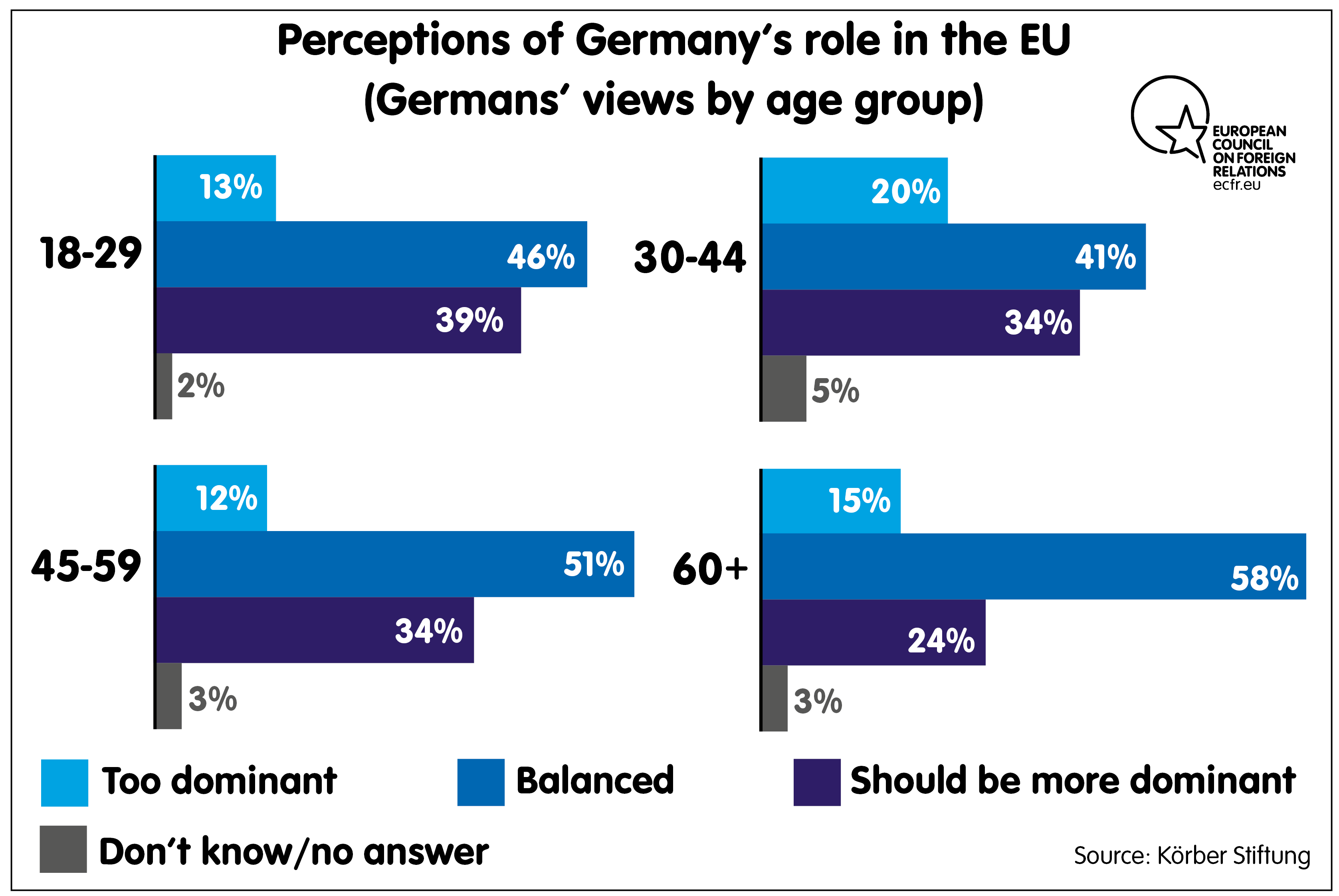

According to many sociologists, in their professional lives, millennials like working in teams. However, when it comes to Germany’s role in the EU, Germans aged between 18 and 29 are relatively supportive of Germany taking on more leadership responsibility. While 46% believe that the country currently strikes a good balance in this area, 39% think it should be more assertive, the largest proportion of any age group.

Migration

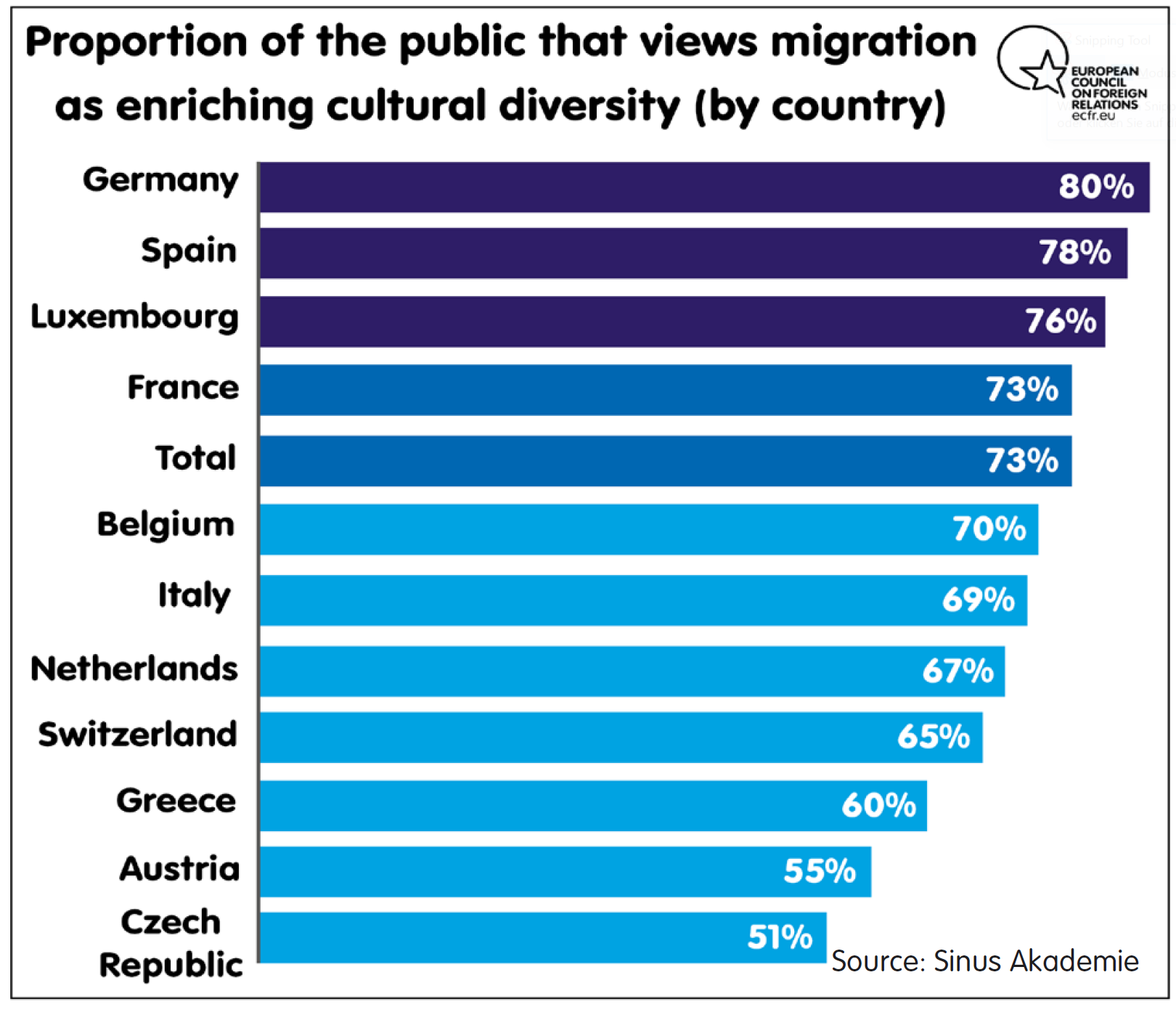

Young Germans are more open to migration than their counterparts in other European countries, with 80% believing it enriches their cultural diversity.[28] Although Germans generally support the establishment of Obergrenze (an upper limit on the number of immigrants allowed into their country), the young reject this idea. The young also have more reservations than other age groups about support for African states that violate human rights to prevent refugees from travelling to Europe.

Young Germans’ ideal EU, it appears, would be carefully led by Germany, and focused on European unity, peace, and ecology. It might be more involved in foreign policy, but not militarily. It would also be more welcoming to migrants.

It is the ideal of an EU that could afford the luxury of indifference to the outside world. Taken together, the polls paint a picture of young Germans’ views as being almost stereotypically German, as they reject hard choices and are wary of anything military. Their focus is on safeguarding what has been achieved rather than creating something new (interestingly, in a rare agreement, both a young AFD MP and a young Green activist interviewed for this policy brief spoke about preserving the achievements of the enlightenment). Most German millennials regard the EU as a success story, and fear that its achievements may eventually be lost because many take them for granted. Defending the status quo is the common denominator in German millennials’ views. As one of the respondents in a youth study noted, they hope above all that “everything remains as it is”.[27]

This may explain why, in Germany, fringe parties, including the AfD and Die Linke, have relatively old memberships and leaders. In contrast, young people are at the forefront of such parties in many other European countries. For instance, a 35-year-old leads a new group rivalling Geert Wilder’s Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, while the head of Italy’s Five Star Movement is 31.

Most, if not all, German millennials appear to be unambitious about creating a new vision for the EU. Retaining what they have is largely enough for them. As journalist Simon Kuper notes, “Brexit and Trump have mobilised a generation of young people, taught them that government matters, and shown that not screwing up is a lofty goal”.[29] This may also explain the high support for conservative parties. The philosopher Michael Oakeshott wrote in 1956 that to be conservative “is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss”.[29]

Kleine Frage / Small question — Erich Fried

Glaubst du

du bist noch

zu klein

um große Fragen zu stellen?

Dann Kriegen

die Großemn

dich klein

noch bevor du

groß genug bist

Do you think

you are still

too small

to ask

big questions?

In the case,

the big ones

are making you small

even before

you are big enough

the big ones

are making you small

even before

you are big enough

About the author

Ulrike Franke is a policy fellow at ECFR, where she works on German politics and German and European security and defence policy – topics on which she has written extensively. She joined ECFR in 2015. Ulrike holds a BA from Sciences Po Paris and a double summa cum laude MA degree from Sciences Po Paris (Affaires internationales/Sécurité internationale) and the University of St. Gallen (international affairs and governance). She is currently finishing a PhD at Oxford University. Before joining ECFR, Ulrike was managing editor of the St. Antony’s International Review (STAIR), Oxford’s journal of international affairs. Ulrike was also part of UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counter-terrorism Ben Emmerson’s research team, working on drone use in counter-terrorism. Prior to this she worked as a part-time research assistant at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

Acknowledgements

This paper is yet another example of ECFR’s long-standing commitment to discussing Germany’s role in Europe. ECFR Berlin extends our gratitude to Stiftung Mercator for its continuous and generous support of our research. The author would like to thank Körber Stiftung for providing polling data from the “Berlin Pulse” broken down by age group. She would also like to thank all interviewees, particularly members of parliament, for taking the time to lay out their vision for the EU.

Footnotes

[1] Georg Blume, “Warten auf die deutschen Freunde”, Spiegel, 23 February 2018, available at http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/frankreich-emmanuel-macron-sorgt-sich-um-angela-merkel-a-1194275.html.

[2] Maria Fiedler and Ulrike Scheffer, “Der Ton wird rauer”, Tagesspiegel, 12.December 2017, available at https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/neuer-bundestag-der-ton-wird-rauer/20702834.html.

[3] Emmanuel Macron, speech at Humboldt University, 10 January 2017, available at https://www.rewi.hu-berlin.de/de/lf/oe/whi/FCE/2017/rede-macron.

[4] Peter Moore, “How Britain Voted”, 27 June 2016, available at https://yougov.co.uk/news/2016/06/27/how-britain-voted/.

[5] Simon Shuster, “The U.K.’s Old Decided for the Young in the Brexit Vote”, Time, 24 June 2016, http://time.com/4381878/brexit-generation-gap-older-younger-voters/.

[6] Nicole Puglise, “Exit polls and election results – what we learned”, Guardian, 12 November 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/12/exit-polls-election-results-what-we-learned.

[7] Marianne Stewart, Harold Clarke, Matthew Goodwin, and Paul Whiteley, “Yes, there was a ‚youthquake‘ in the 2017 snap election – and it mattered”, New Statesman, 5 February 2018, available at https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2018/02/yes-there-was-youthquake-2017-snap-election-and-it-mattered.

[8] Florent Latrive, “Age, diplôme, revenus… qui a voté Macron? Qui a voté Le Pen?”, France Culture, 7 May 2017, available at https://www.franceculture.fr/politique/age-diplome-revenus-qui-vote-macron-qui-vote-le-pen.

[9] Kate Taylor, “‘Psychologically scarred’ millennials are killing countless industries from napkins to Applebee's — here are the businesses they like the least”, Business Insider, 31 October 2017, available at http://www.businessinsider.de/millennials-are-killing-list-2017-8?op=1; William Cummings, “Millionaire to Millennials: Your avocado toast addiction is costing you a house”, USA Today, 16 May 2017, available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/05/16/millionaire-tells-millennials-your-avocado-addiction-costing-you-house/101727712/.

[10] “Soziale und demografische Daten weltweit: DSW-Datenreport 2017”, Deutsche Stiftung Weltbevölkerung, August 2017, available at https://www.dsw.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DSW-Datenreport_2017_web.pdf. In comparison, 44% of Nigerians are younger than 15, and only 3% 65 or older.

[11] Sibylle Krause-Burger, “Politik als Spaß und Spiel”, Stuttgarter Zeitung, 5 February 2018, available at https://www.stuttgarter-zeitung.de/inhalt.krause-burger-kolumne-politik-als-spass-und-spiel.99764992-a36e-45c4-bee7-1d791c563bd9.html.

[12] “Krasse Rede – Juso-Chef Kevin Kühnert: Seine Rede gegen Koalitionsverhandlungen mit der Union”, Bild, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qku501qekk.

[13] Florian Naumann “Merkel und der Joghurt: Deshalb sorgt ein Tweet von Juso-Boss Kühnert für Aufsehen”, Merkur, 26 January 2018, available at https://www.merkur.de/politik/merkel-joghurt-und-wgs-deshalb-sorgt-ein-tweet-von-juso-boss-kuehnert-fuer-aufsehen-zr-9560353.html.

[14] Civey survey result, presented on 8 February 2018, at “young+restless. Sind die Alten überfordert? Welche Möglichkeiten haben junge Menschen in Parteien?”.

[15] “Wenn wir die GroKo ablehnen, gibt es Neuwahlen und wie die SPD dann dasteht ist völlig ungewiss!”, Jusos, available at http://www.jusos.de/content/uploads/2017/12/Argucards.pdf.

[16] See, for instance, “Vorurteile gegen junge Politiker: Wo ist denn die Frau Abgeordnete?‘“, Spiegel, 25 January 2018, available at http://www.spiegel.de/video/altersdiskriminierung-politiker-schildern-ihre-erlebnisse-video-99013291.html; and Sascha Lobo, “Warum die Alten neidisch auf die Jugend sind”, Spiegel, 24 January 2018, available at http://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/web/zukunft-der-arbeit-warum-die-alten-neidisch-auf-die-jugend-sind-a-1189590.html.

[17] “Die Shell Jugendstudie”, Shell, available at https://www.shell.de/ueber-uns/die-shell-jugendstudie.html.

[18] “Generation Biedermeier”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 11 September 2010, available at http://www.sueddeutsche.de/karriere/studie-zur-jugendkultur-generation-biedermeier-1.998533.

[19] Civey survey result, presented on 8 February 2018 at “young+restless. Sind die Alten überfordert? Welche Möglichkeiten haben junge Menschen in Parteien?”.

[20] Sascha Lobo, “Warum die Alten neidisch auf die Jugend sind”, Spiegel, 24 January 2018, http://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/web/zukunft-der-arbeit-warum-die-alten-neidisch-auf-die-jugend-sind-a-1189590.html.

[21] “Vereintes Europa”, Junges Liberale, available at https://www.julis.de/politik/themen/vereintes-europa/.

[22] “Die Phrasen der Jusos”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23 January 2018, available at http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/die-phrasen-der-jusos-im-faz-net-countdown-15412383.html.

[23] “The Berlin Pulse”, Körber Stiftung, available at https://www.koerber-stiftung.de/en/berlin-foreign-policy-forum/the-berlin-pulse. The author would like to thank Körber Stiftung for providing polling data broken down by age group.

[24] “Generation What?”, RTE, available at http://www.generation-what.ie/portrait/data/europe

[25] “Die Generation Y ist überhaupt nicht faul”, European, 26 August 2014, available at http://www.theeuropean.de/kerstin-bund/8848-die-arbeitswelt-im-21-jahrhundert.

[26] “Love it, leave it or change it?”, Bertelsmann Stiftung, February 2017, available at https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/EZ_flashlight_europe_2017_02_DT.pdf

[27] “Für die Zukunft wünsche ich mir, dass alles so weiter läuft wie bisher.” (m, 31, 1 Kind). Robert Vehrkamp, Stephan Grünewald, Christina Tillmann, and Rose Beaugrand, “Generation Wahl-O-Mat Fünf Befunde zur Zukunftsfähigkeit der Demokratie im demographischen Wandel”, Bertelsmann Stiftung, p. 11.

[28] Poll “Generation What 2017”, Sinus, available at https://www.sinus-akademie.de/fileadmin/user_files/downloads/Generation_What/Generation-what-europaeischer-abschlussbericht.pdf.

[29] Simon Kuper, “Brexit, Trump and a generation of incompetents”, Financial Times, 14 December 2017, available at https://www.ft.com/content/3a31862c-df91-11e7-a8a4-0a1e63a52f9c.

[30] Sebastian Payne, “Where next for the Conservatives?”, Financial Times, 14 December 2017, available at https://www.ft.com/content/f425c404-df95-11e7-a8a4-0a1e63a52f9c.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.